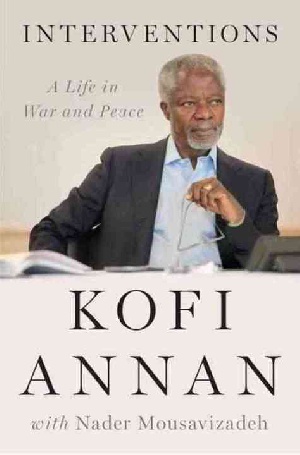

In Interventions: A Life in War and Peace, former United Nations Secretary General, Kofi Annan, explores the ups and downs of his UN career, bringing into sharp focus the often complex and thankless task of diplomacy and the sometimes elusive search for solutions to conflicts. It highlights the contestations in the UN and how the Secretariat in New York sometimes finds itself trapped between fiercely competing powers attempting to secure individual victories in a field of many players.

IT’S not every day that you get diplomats criticising each other openly. But, somehow, somewhere, something has to be said, if only in memoirs. Kofi Annan chides his predecessor, Boutros Boutros-Ghali, for his ‘secretive’ style of management. But, it seems, nowhere was Boutros-Ghali’s ‘secretive’ approach laid more bare than in the humiliation of the US in Mogadishu.

At a time when the Department of Peacekeeping Operations (DPKO), of which Annan was then under-secretary-general, was trying to deliver food to the starving in Somalia, Boutros-Ghali seemingly shared the US belief that capturing the warlord, Mohammed Farar Aidid was a priority.

While US Special Forces to hunt down Aidid arrived in Somalia in late August 1993 with Boutros-Ghali’s knowledge, the DPKO only came to learn of this on October 3, 1993 when the attempt to capture Aidid went horribly wrong. Two helicopters were shot down and 18 US soldiers killed and many more wounded.

The omission in this account is that Annan does not say if and how Boutros-Ghali responded or whether he had any explanation to give to the Security Council or how he faced his sidelined subordinates in the DPKO.

Annan says “the establishment of the International Criminal Court represents a major victory for the rule of law in international affairs.” It was created to “put an end to a global culture of impunity.”

Annan published his book ten years after the ICC was established. He acknowledges that “critics are correct most of the early cases are from Africa.” He further adds that “in all these cases, it is impunity, not Africans, that is being targeted.”

But he fails to discuss why, in ten years, the ICC has not been active in other regions of the world where “crimes against humanity” have been committed and where a “culture of impunity” similarly exists. This omission, to say the least, is inexcusable for a man who has, throughout the book, ably demonstrated his dislike for impunity. Is impunity a preserve of Africa?

Annan explains the difficulties he had dealing with the US and how much he opposed the US invasion of Iraq. But he does not say why it took him over a year after the invasion to call it “illegal” when it was clear the US had disregarded international law.

Annan gives examples of his refusal to be bullied by the US. At the height of Iraq’s weapons inspections debate, US Secretary of State, Madeleine Albright, phoned Annan asking him if he had received a statement drafted by the US, UK and France, condemning “Iraqi’s intransigence.” All Albright wanted Annan to do was to sign it. Annan declined.

The US speaks well about respect for institutions and the rule of law. But Annan paints a picture of a country that is so often preoccupied with having its way, sometimes even at the expense of international law.

Annan says when he accepted to mediate in the Syria conflict, “impossible mission” was written all over. Annan ends this subject rather inconclusively.

Although it’s understood that the mission to Syria came when he was reviewing the draft manuscript, readers would have wanted to know, for instance, what finally made this veteran diplomat give up on his much-talked about six-point plan. Was it a tacit admission that the prophets of “impossible mission” were right or was the task simply out of hand?

The strength of the book lies in Annan’s ability to tell the inside story and share with his readers some of the complex issues he had to deal with but which he could not publicly discuss as he does in the book. It is also a very good summary of a 50-year career. Few autobiographies admit failure. But Annan does not shy away from discussing the low moments, among them, the UN failure to stop the Rwanda genocide and the Srebrenica massacre.

Overall, Interventions: A Life in War and Peace is an interesting book, a worthy addition to the shelf that not only takes you inside the workings of the UN, but also the tough decisions that have to be made regarding world peace.

General News of Friday, 15 November 2013

Source: tribune.com.ng