Yesterday's front pages were perhaps worse than the average: a toilet bowl full to the brim with human faeces, maggots swimming in the rot and crawling from its edges, leapt out from the Ghanaian Chronicle; whilst the Daily Graphic re-printed graphic images of a recent victim of mob injustice in Adabraka.

The photographs, understandably, drew disgust and anger from some members of the public, their views discussed on Joy FM"s 12pm news bulletin. Questions were raised about the moral, ethical and professional standards of newspapers which choose to publish such deliberately shocking images: are they wrong to do so? When is it justified, and when is it simply wrong?

The Statesman welcomes such debate, although hardly from the sidelines: twice in recent weeks we too have chosen (though with a very heavy heart) to publish photographs which some have found offensive, of social injustices we believed ought to be exposed and changed.

The first, on April 20, was a case of "instant injustice," as Mohammed Issah Yussif, a 29-year-old suspected thief from Nima, was almost killed outside the Statesman offices, saved only by the intervention of this newspaper’s Editor-in-Chief. A gang of some 50 local citizens had captured the fleeing alleged criminal and decided to serve him with his punishment on the spot: hitting him with blocks, metal crowbars, sticks and any weapon available, and inflicting serious head and other injuries, depicted in colour on our front page.

Our decision to publish the photograph was based on a heartfelt revulsion at the kind of collective behaviour which results in such swift and often unjust "instant justice," and by the obvious passivity of many Ghanaians towards the phenomenon. We had carried a front page comment on it more than a year ago. But, no one took notice, it seemed.

But, a recent "vox pop" survey carried out by our sister paper, The Saturday Statesman, the following week after the Issah Yussif incident revealed that many Ghanaians actually support what we believe to be such a clear-cut breach of human rights and the rule of law in this country.

We published the photograph, alongside a hard-hitting editorial on the dangerous acceptance of mob injustice, because we felt it would make a difference: we wanted Ghanaians to wake up to the inhumanity of this acceptance, encouragement even, of mob behaviour, and we believed we might achieve that by bringing such cases to public light.

Days later, on April 20, we again published a photograph so disturbing that many readers called to complain: Nana Kwame Sarpong, 35, died in police custody in the Kumasi Central Prison. According to eye witnesses, the suspected car thief was repeatedly beaten and tortured by police officers for two days after he was admitted.

Our correspondent had sneaked in to the mortuary at the Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital to look for the body; beaten and disfigured, there was no denying that Sarpong had suffered brutal treatment. The photographs were taken to be tendered as evidence to the police, to be used in their investigation of the case; they were also published in this newspaper, as evidence to the public of the kind of abuses which continue to occur in our justice system.

Again, our motivation was a moral one, and fits within a wider moral agenda of this newspaper. We did intend to shock, but because we thought it had a justifiable purpose and could have a constructive end.

Time and again, journalists witness unpleasant, even abhorrent things - indeed, in some senses, perhaps it is their job to do so. It is also their job to make sense of what they see, and to present it and translate it in a meaningful way to their audience. We believe that a sensible, sensitive and considered handling of these abominations can be a force for change and for good.

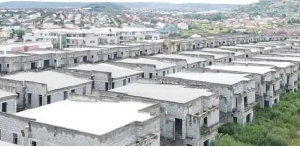

In the case of both the Graphic and the Chronicle, for example, we believe the publications were justified. As acting Chronicle editor, James Kwashie, has asserted, it is an issue of public interest and importance that students at the country’s most highly regarded university are living in such squalid conditions: what does it say for the future leaders of this country? If it takes a newspaper splash to make the authorities take action, then the newspapers are only doing their job.

The decision of the Graphic to re-raise the issue of mob justice through the re-use of a disturbing photograph also has some moral justification – based in a belief, shared by The Statesman, that the practice must be brought to an end. But not every shocking picture is meant for public eyes.

The back page of the Daily Dispatch yesterday was even more gruesome, as the murder of a young man near Obuasi in the Ashanti Region was illustrated with a photograph of the bludgeoned head – the face unrecognisable, blood and brains spilling onto the floor.

The alleged killer, Kofi Iddrisu, is also shown on the picture; as the newspaper reports, "Iddrisu was caught by some youngmen in his bathroom where he was blood stains [sic]. He was brought to the spot of the incidence [sic], made to lick the blood… He has since been handed over to the Fomena Police." The use of such pictures, and the carrying of such reports, not only contribute little to the national consciousness, the public interest; but also serve to increase ignorance and even barbarity – which we believe a responsible media should be working to challenge.

Mob injustice is an area which campaigning newspapers want to change the public perception on; unsanitary conditions at Legon are not widely known – and a public expose might force an improvement for students. But what is the justification for publishing photographs of a murder – a crime which any Ghanaian would agree is a shameful act? Where is the responsibility in recounting a detailed report of the treatment of Iddrisu, without bringing any perspective, consulting any human rights advocate or legal practitioner, taking an editorial stance?

Another example of a seemingly pointless but shocking display was the controversial Daily Graphic front page last year, which showed the dismembered and disfigured bodies of the 37 victims of a tro tro accident in the Ashanti Region. The accident had already been declared a national tragedy; the country was already in shock, and there seemed to be no reaction or no result which could come out of the disturbing photograph, other than anger from the families at the lack of respect shown for the victims, and perhaps elevated sales from the cheap sensationalism tactic.

Clearly, there are no hard and fast rules with photography in journalism, just as wider questions of ethics and morality can often be a grey area. But today, The Statesman urges every media house in this country to take these questions more seriously.

Does respect for the dignity and privacy of an individual and their family outweigh the public interest value of a picture? What is the positive purpose you hope to achieve from publishing a negative photograph? Are your motivations based on moral reasoning, or simply cheap commercialism? Whilst increased sales may be a by-product of shock images, they should never, in the view of this newspaper, be the propelling motivation.

On questions of ethicality, we can offer no firm answers: but we can offer a conscience, a genuine endeavour to do the right thing, and an honest call on our colleagues in the media to join with us in this goal.

Editorial News of Friday, 11 May 2007

Source: Statsman