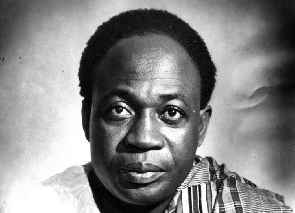

The impression that the British colonial government left huge sums of money to Kwame Nkrumah’s government to usher Ghana to independence - which they accuse him of “wasting” before February 24, 1966 coup is one of the biggest falsehoods lingering for so long which must be corrected. Most often than not, you will hear cynics of Nkrumah making reference to this spurious claim without any exact proof but just to show the cause of their unrepentant loathes for him.

History is written for heroes, not villains. But in today’s Ghana, the issues of the elitist few who were long ago rejected are struggling to rewrite Ghana’s history in a way that suits their interests. Do we still allow these people to change our history to make villains appear as heroes and reactionaries appear as democrats under the guise of multi-party democracy? Absolutely not. In this article, the aim is to clarify Nkrumah’s internal self-government generated revenue for the Gold Coast, as part of the funding of the Five-Year Development Plan from 1951-1956 from the Cocoa Duty and Development Funds (Amendment) Act of 1954, and also explain a bit of the formation of the National Liberation Movement (NLM) in November 1954 and the collapse of the British economy after the Second World War.

Cocoa Duty and Development Funds (Amendment) Act

First, the Cocoa Marketing Board (CMB) was established in 1947. The purpose of the establishment of the Board was to look into a series of disputes between cocoa farmers and their European buying partners. Initially, cocoa farmers used to sell their produce directly to a cooperative of European buyers but their dissatisfaction with the prices they were offered a new arrangement that was designed to give them more leverage against European buyers and to insulate them against fluctuations in the world market price for cocoa.

Ghana’s main source of income then came from the export of cocoa. And the world price of cocoa was steadily on the rise. In 1949-50 the country had received £ 178 for each ton of cocoa sold abroad. In 1950-51 the figure rose to £ 269. In the two following year, it was slightly lower. But in 1953-54 it was £358 a ton. And in 1954, it reached £467 per ton, the highest ever paid till then. All appeared necessary to spend money on the modernization of the Gold Coast economy. (Basil Davidson, Black Star)

But the real dispute on cocoa and the Cocoa Marketing Board (CMB) begun when it became politicized after the then Minister for Finance K.A. Gbedemah introduced the Cocoa Duty and Development Funds (Amendment) Bill in 1954 which fixed the farm-gate price of cocoa at 72shillings (£3 12s) per 60lb load for four years.

Here is what Gbedemah said in the concluding debate in parliament:

“[F]irstly, that it is not in the general interest of the Gold Coast to be subjected to considerable or frequent fluctuations in the prices paid for its cocoa; secondly, that having regard to all other circumstances which obtain in the Gold Coast today, the present price paid locally of cocoa is fair, reasonable and provides an incentive to increased production; thirdly, that it follows that it is in the general interest that the cocoa farmer should receive a good and steady income for a period of years….and lastly, that the funds which may accrue to Government through the fiscal policy it is now establishing should be concentrated as far as possible on expanding the economy of the country as a whole with special emphasis on its agricultural sector”. (Ekow Nelson, Nkrumah’s Cocoa Policy and Economic Development).

In essence, cocoa reserves were kept in London as investment from the revenues generated from the cocoa duty with the hope of making the country a better place to live in the near future. Sadly, this development led to agitations from the cocoa area of Ashanti, especially the Asantehene, who girded the separatist movement while calling for a Federal State in order to ensure that all revenue from cocoa export are vested in the Asante Kingdom, not to the central government.

According to Richard Mahoney, political independence, in short, did not mean economic independence to Nkrumah. He noted that “the vagaries of the world prices of cocoa (which provided Ghana with about 70 percent of its foreign-exchange earnings) put development plans on a precarious base and seemed to necessitate substantial investment in the area of cash-crop diversification.

Following the British advice, however, Nkrumah had left Ghana’s $500 million of reserves, accumulated during the colonial period, in long-term, low-interest British securities; thus this great source of productive investment was unavailable (to Nkrumah’s post-independence government) in 1959” (Mahoney, “J.F.K. Ordeal in African”). Thus, to a larger extent, this money was not made outright to Nkrumah. For example, in 1953, the Cocoa Marketing Board sold cocoa to a total of £ 74 million. But the amount paid to Ghana was only £ 28 million.

(Basil Davidson, Black Star)

Collapse of the British economy after Second World War

It became obvious to Nkrumah that Ghana was in fact helping to finance Britain banking system. After the Second World War, the British economy collapsed for many reasons. It includes, first of all, the conversion of its industrial to entirely war production. And also due to the severe destruction caused by Germany and Hitler’s forces, the economy was not able to sustain production for its citizens.

More so, the destruction created the need to borrow massively and they lost much of their productive capacity, which resulted in the accumulation of massive external debts—particularly to the USA. It was because of these and other devastations of the war in other European countries that led to the Bretton Woods Conference in 1944 – which Marshall Plan was an economic recovery program for Western European economies after World War II. (Michael J. Hogan, “The Marshal Plan: America, Britain and the reconstruction of Western Europe 1947-1952”).

Therefore, in concluding, the British colonial government in the Gold Coast (now the Republic of Ghana) was not a charitable organization to have invested in the raw materials (cocoa, gold, diamonds, manganese, timber and others) and largesse enough to have returned the profits to the Gold Coast, let alone leaving huge surpluses for Kwame Nkrumah to “waste” at a time when Britain could not find feet to fend for the Queen and her people.

Bibliography

Basil Davidson, Black Star: A View of the Life and Times of Kwame Nkrumah, 1973

Ekow Nelson, Nkrumah’s Cocoa Policy and Economic Development

Richard D. Mahoney, J F K Ordeal in Africa, 1983. Oxford University Press, New York, Oxford

(Michael J. Hogan, “The Marshal Plan: America, Britain and the reconstruction of Western Europe 1947-1952”).

By: Michael Sumaila Nlasia

The author is a graduate of law at the Ghana Institute of Management and Public Administration.

Email address: marcusgarvey.snr@gmail.com

Click to view details

Opinions of Wednesday, 24 February 2021

Columnist: Michael Sumaila Nlasia

February 24, 1966 Coup and the lie that Nkrumah received huge money from the colonial government

Opinions