A paramilitary unit controlled by then-Gambian president Yahya Jammeh summarily executed more than 50 Ghanaian, Nigerian, and other West African migrants in July 2005, Human Rights Watch and TRIAL International said Wednesday, 16 May 2018.

Interviews with 30 former Gambian officials, including eleven officers directly involved in the incident, reveal that the migrants, who were bound for Europe but were suspected of being mercenaries intent on overthrowing Jammeh, were murdered after having been detained by Jammeh’s closest deputies in the army, navy, and police forces. The witnesses identified the “Junglers,” a notorious unit that took its orders directly from Jammeh, as those who carried out the killings.

“The West African migrants weren’t murdered by rogue elements, but by a paramilitary death squad taking orders from President Jammeh,” said Reed Brody, counsel at Human Rights Watch. “Jammeh’s subordinates then destroyed key evidence to prevent international investigators from learning the truth.” Martin Kyere, the sole known Ghanaian survivor; the families of the disappeared; the family of Saul N’dow, another Ghanaian killed under Jammeh; and Ghanaian human rights organizations on May 16, 2018, called on the Ghanaian government to investigate the new evidence and potentially seek Jammeh’s extradition and prosecution in Ghana.

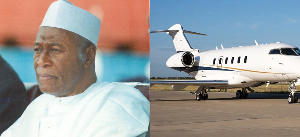

Jammeh’s 22-year rule was marked by widespread abuses, including forced disappearances, extrajudicial killings, and arbitrary detention. He sought exile in Equatorial Guinea in January 2017 after losing the December 2016 presidential election to Adama Barrow.

The insiders interviewed by TRIAL International and Human Rights Watch include some of the highest-ranking security commanders in the Gambian government at the time, as well as several officials present at the arrest, detention, and transfer of the migrants, a Jungler who witnessed the killings, and two who participated in a subsequent cover-up. Another Jungler who witnessed the killings was interviewed on the radio.

They said that the migrants – including some 44 Ghanaians and several Nigerians – were arrested in July 2005 at a beach where they had landed, then transferred to the Gambian Naval Headquarters in Banjul, the capital. They were detained there in the presence of the inspector general of police, the director general of the National Intelligence Agency (NIA), the chief of the defense staff, and the commander of the National Guards. At least two of them were in telephone contact with Jammeh during the operation. The head and several members of the paramilitary Junglers were also there.

The officials divided the migrants into groups and then turned them over to the Junglers. Over one week, the Junglers summarily executed them near Banjul and along the Senegal-Gambia border near Jammeh’s hometown of Kanilai.

Kyere was detained in a Banjul police station, then driven into the forest. In February 2018, he explained to Human Rights Watch and TRIAL International how he escaped, just before other migrants were apparently killed.

“We were in the back of a pickup truck,” he said. “One man complained that the wires binding us were too tight and a soldier with a cutlass sliced him on the shoulder, cutting his arm, which bled profusely. It was then that I thought, ‘We’re going to die.’ But as the truck went deeper into the forest, I was able to get my hands free. I jumped out from the pickup and started to run into the forest. The soldiers shot toward me but I was able to hide. I then heard shots from the pickup and the cry, in Twi [Ghanaian language], ‘God save us!’”

Kyere helped the Ghanaian authorities identify many of the dead and travelled around Ghana to locate their families and promote efforts to seek justice.

Despite measures in ensuing years by Ghana as well as the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) and the United Nations (UN) to investigate the case, no arrests have ever been made.

The Bulletin of the UN Department of Public Affairs said that an ECOWAS/UN report, never made public, concluded that the Gambian government was not “directly or indirectly complicit” in the deaths and disappearances but rather that “rogue elements” in Gambia’s security services “acting on their own” were probably responsible.

The new evidence makes clear, however, that those responsible for the killings were the Junglers, who were not rogue elements, but a disciplined unit operating under Jammeh.

In October 2017, Gambian and international rights groups, including Human Rights Watch, and TRIAL International, launched the “Campaign to Bring Yahya Jammeh and his Accomplices to Justice” (#Jammeh2Justice), which calls for prosecuting Jammeh and others who bear the greatest responsibility for his government’s crimes under international fair trial standards.

President Barrow of The Gambia has suggested that he would seek Jammeh’s extradition from Equatorial Guinea if his prosecution was recommended by the country’s Truth Reconciliation and Reparations Commission, which is expected to begin work in the next few months with an initial two-year mandate. The government and internationalactivists and academics have said that the political, institutional and security conditions do not yet exist in The Gambia for a fair trial of Yahya Jammeh which would contribute to Gambia’s stability.

President Teodoro Obiang of Equatorial Guinea said in January that he would “analyze [any extradition request] with [his] lawyers.” A week later, however, he said “we have to protect him [Jammeh], we have to respect him as a former African head of state, because that is what is going to ensure that the other heads of state of Africa who have to leave power do not fear for subsequent harassment.”

Ghanaian groups noted that the UN Convention against Torture, which Equatorial Guinea has ratified, requires a country in whose territory a torture suspect is found to refer the case for investigation or extradite that person.

“Our investigation has enabled us to get closer to the truth about this horrible massacre,” said Benedict De Moerloose, head of Criminal Law and Investigations for TRIAL International. “The time has now come to deliver justice for the victims and their families.”

The July 2005 killings

On July 22, 2005, Gambian police forces arrested approximately 50-56 foreigners in Barra, a town facing Banjul on the opposite shore of the River Gambia. It is difficult to determine the numbers with certainty but it appears the group included about 44 Ghanaians, as many as ten Nigerians, two or three Ivoirians, two Senegalese, and one Togolese. The detained men and women, as well as one additional Gambian who was later arrested, were believed to have been killed in the ensuing week and buried near Banjul and Kanilai. The disfigured bodies of eight of the migrants were found in Brufut, on the outskirts of Banjul, on July 23, the day after their capture. No other bodies have been recovered.

Between March 2017 and May 2018, Human Rights Watch and TRIAL International interviewed 30 former Gambian security officials both inside and outside of Gambia, including 11 officers directly involved in the incident, as well as Kyere, the survivor, another Ghanaian who left the group shortly before the original arrest, the families of 15 of the Ghanaian victims, and two of the Ghanaian investigators. The organizations also translated a long radio interviewwith a former Jungler, Bai Lowe.

The migrants – including two women – had set off from a beach in Saly Mbour in Senegal in a hired motorized canoe hoping to meet up with a boat that would take them to Europe. They were unable to make contact with the boat, however, and landed in Barra, where they were arrested on July 22 – “Revolution Day” celebrating Jammeh’s 1994 coup. “They lined us up, pointing guns at us, and marched us to the Barra police,” Kyere said.

Several officials interviewed said that Gambian intelligence had previously received information regarding a planned coup by mercenaries and may have mistaken the migrants for these mercenaries.

Jammeh and his ministers, the chiefs of Gambia’s security forces, and civilian dignitaries were attending a festival at the July 22 Square in Banjul. Several witnesses said that inspector general of police, Ousman Sonko – who is currently detained in Switzerland on charges of crimes against humanity – was at the ceremony and received a phone call that foreigners had been apprehended. Officers who were there said that Jammeh was informed and he got up and left with his security detail for his nearby compound.

Witnesses said that Sonko asked the Navy to transfer the group by boat from Barra to the Naval Headquarters in Banjul. The naval boat Fatima I had to make two trips. Kyere, who was on the second crossing, observed when they were reunited at headquarters that most of those on the first trip had been beaten and stripped of their possessions. One commander said that at least two of the high-ranking officials at the headquarters, Sonko and the National Intelligence Agency director, Daba Marenah, called Jammeh from the Naval Headquarters.

The head and several members of the Junglers, an unofficial paramilitary unit of about 12 to 25 soldiers drawn from the State Guard, were also at the Naval Headquarters. The Junglers took their name from the fact that some members had received jungle survivor training. They were also known as the “Patrol Team” because their original duties included patrolling the Gambia-Senegal border around the presidential residence in Kanilai. The State Guards from which the Junglers were drawn played a key role in protecting Jammeh, and they received frequent and intense training, from Iran, Libya and Taiwan, among others. From their creation in 2003-2004 until Jammeh’s fall in 2017, the Junglers were implicated in serious human rights violations, including torture, sexual violence, enforced disappearances, and killings.

Throughout the Junglers’ existence, Jammeh was in regular communication, often daily, with its leader, who at the time of the migrant killings was Tumbul Tamba. One former Jungler said Tamba received direct operational orders from Jammeh and would then convene the Junglers to brief them on the operation and to communicate Jammeh’s orders. “The big man said to ‘finish them,’” was how Tamba would convey orders to kill, said the former Jungler. “Tamba reported after every mission to the president.”

On July 23, the migrants were divided into groups and taken by buses to several locations around Banjul, including the Junglers’ unofficial headquarters, and several police stations and army barracks. Kyere said he was held at the Bundung Police Station. The police also arrested Lamin Tunkara, a Gambian who was working with the captain of the vessel which was to transport the migrants to Europe. Tunkara was later taken in the same pickup truck from which Kyere escaped into the forest. His family has never seen Tunkara again.

A first group of migrants was taken on July 23 from the Kanifing police station in two vehicles to Brufut, on the outskirts of Banjul. A former Jungler said that eight migrants were then executed by seven Junglers, assisted by several regular soldiers, with machetes, axes, knives, and sticks and left in the bushes near “Ghanatown” in Brufut. The migrants were handcuffed while they were slaughtered. A former police commissioner who arrived on the scene confirmed that the bodies had been badly beaten. “One had had his head smashed with something heavy…another had his face broken completely… [a third] had blood coming out of his ears, nose, eyes.” Two former Junglers said that the migrants were killed this way following a Jammeh directive issued after the 2004 murder of a journalist,Deyda Hydara, not to use guns in killings in Gambia. The discovery of eight dead bodies with cuts and trauma wounds was reported in the Gambian press.

Based on numerous accounts, two of the Ghanaian migrants in that first group escaped during this time and sought refuge in Ghanatown, but were turned over by local leaders to the police. They have not been heard from since.

The other migrants, probably about 45, were held for a longer period in several other places of detention around Banjul, apparently while further investigations were carried out. About a week later, various Junglers rounded them up and took them to the town of Kuloro, then took them in several pickup trucks and other vehicles toward Kanilai.

Just across Gambia’s southern border in the Casamance region of Senegal, in an operation overseen by Tamba, the Junglers’ head, two Junglers covered the heads of migrants in plastic and shot them. Since it was outside the Gambia, the Junglers could use their guns. These bodies were dumped in nearby wells, including one in an abandoned village in Senegal, and another near Jammeh’s compound in Kanilai. One of the Junglers involved told Human Rights Watch and TRIAL International that the wells were covered with stones. The area across the border had been used by the Junglers as a killing and dumping ground in at least two other cases.

Bai Lowe, one of the former Junglers, said in a radio interview: Tumbul [head of the Junglers] said let the guys [the two Junglers] say, “We are going to kill you in the interest of our nation.” He said once the guys say that, then the boys are not responsible but The Gambia as a nation will be responsible...There are these old wells in the bush [in Senegal] belong to Fulas [a pastoralist ethnic group] where they fetch water for their cows. Two guys will just bring you to the well, execute you and throw you in the well. That is where I saw them use a pistol to kill…They will just put a plastic bag over your head, shoot you and throw you in the well...They killed up to 40 people.”

One of the migrants escaped at this point and was recaptured at Kankurang near Kanilai. According to Bai Lowe, the escapee was cut to death with a cutlass by another Jungler and his dismembered body was put in a plastic sack.

After these killings, Jammeh gave two bulls to the Naval Headquarters. A former inspector general of police who later investigated the case surmised to Human Rights Watch and TRIAL International that this was to thank the Navy for its “good work.”

Kyere said that he was loaded into the back of a white double-cabin pickup truck, along with seven other migrants. The truck went first on a highway, then on a dirt road and into a forest, where Kyere jumped from the truck. He spent days wandering in the forest before he came to a village in Senegal where he was given some food. From there, he went to the town of Bounkiling and reported the incident to the Senegalese gendarmerie.

He was treated at the local hospital and given money and travel papers so he could go to Dakar. There, he helped the Ghanaian embassy identify the people he had travelled with and who were believed to have been killed. Back in Ghana, he located many of the victims’ families and, together with the Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative (CHRI), campaigned for full accountability, organizing marches and demonstrations that kept the issue alive.

International Investigations and the Destruction of Evidence

The 2005 killings quickly became a source of tension between Ghana and Gambia, particularly after Gambian authorities refused to cooperate with several attempts by Ghana to investigate the matter. During an August 2005 visit to Gambia by a delegation led by the then-foreign minister – and now president, Nana Addo Dankwa Akufo-Addo, the Gambian foreign minister suggested that the eight migrants whose bodies were found may have been victims of ritual murder. According to the Ghanaians, Jammeh “categorically denied any Gambian Government involvement.”

The Gambian government agreed that a Ghanaian investigative team could visit the country, which it did in March 2006, but, according to an excerpt of the unpublished Ghanaian report printed in a Ghanaian newspaper, “[t]he Ghana team’s attempt to meet with high-level Gambian officials whose functions were related to the subject matter of the team’s visit became entangled in layers of bureaucracy…and it became evidently clear the Gambians were not going to be faithful to their commitment to jointly investigate the subject matter.” By the time a jointECOWAS/United Nations team was formed in 2008 to investigate the killings, the Gambian government had allegedly already taken steps to destroy evidence related to the case.

Three different sources stated that Essa Badjie, who was appointed inspector general of police in July 2008, destroyed the diary log of the Barra police station and made a new log and backdated it. Later, after Badjie was imprisoned following a falling out with Jammeh, he told a friend that Jammeh personally instructed him to forge the records.

Shortly before the ECOWAS/UN mission arrived in Gambia, Badjie and the crime management coordinator met several of the high-ranking officials who had been involved in the case in 2005 at Police Headquarters and warned them against saying anything that would incriminate the government.

“Badjie explained that ‘The Gambia belongs to all of us, we should not see The Gambia defamed or destroyed by anyone, we shall do our best for the country,’” one former senior military officer said. “[Badjie] told me an investigation team was coming to investigate the Ghanaians. He wanted [us] not to say anything that would jeopardize the country's integrity.”

Another former senior military officer said: “The message was ‘remove incriminating evidence.’ They asked for the log book of the boat.” The two seized and destroyed the relevant sections of the naval log books.

In 2009, Gambia and Ghana signed a Memorandum of Understanding acknowledging that the Gambian government was not complicit in the killings but would make contributions to the families as a humanitarian gesture. Jammeh said that the findings “vindicated” his government. At the time, Ghana’s foreign minister, Alhaji Muhammad Mumuni, expressed skepticism about the findings, but accepted the report to bring closure to the families and restore relations between the two countries. Gambia paid US$500,000 in compensation to Ghana, which gave 10,000 Ghana cedis (roughly US$6,800 at 2009 rates) to each of the approximately 27 victim’s families. Six bodies were returned to Ghana. Human Rights Watch and TRIAL International have not been able to ascertain whether the transferred bodies were, in fact, those of the murdered Ghanaians.

In the Memorandum of Understanding following the report, “[b]oth Ghana and Gambia pledged to pursue through all available means the arrests and prosecution of all those involved in the deaths and disappearances of the Ghanaians and other ECOWAS nationals, especially those identified as culprits in the report.” No arrests have ever been made in connection with the case, however.