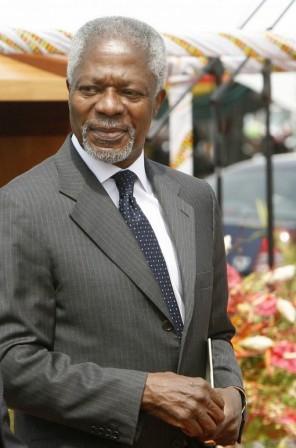

Former UN Secretary General and Chairman of The Elders, Kofi Annan in this interview, discusses his extraordinary career with JP O’Malley and speaks about growing up in Ghana, why he believes governments have to recognise terrorists, and why talking to tyrants sometimes actually saves lives.

Excerpts:

How did growing up in Ghana in the 1950s the decade it gained Independence from Britain shape your political outlook for the rest of your career?

As a teenager, to see this struggle for independence taking place in Ghana was very powerful. I grew up with a sense that fundamental change was possible. For example, to watch the police commissioner who was an Englishman become a Ghanaian, or the Prime Minister become a Ghanaian, it gave me optimism and hope. I saw that things can change, and I had a sense that I could help change things, because I had seen it happen at such an early age.

Where did the UN go wrong in its peacekeeping missions in Somalia, Rwanda and Bosnia in the 1990s?

Until the end of the Cold War, the Security Council was in a way divided. It wasn’t easy to reach agreements on conflicts in which the Security Council should intervene. In most cases, they had intervened in inter-country conflicts, where the parties came to agreements, and invited the UN to come and monitor. So they were fairly stable environments.

After the early 1990s, we got involved in internal situations: Somalia was internal, so was Rwanda, as was Yugoslavia, leading to Srebrenica.

That required a different type of skill: to defend some of the civilian populations in the vicinity. That was really a qualitative and dramatic change in UN operations.

How did you feel in 1994 when you were asking various governments around the world to intervene in the genocide in Rwanda but they wouldn’t? It was a very painful experience for me, but we have to understand the context: we were trying to cope with Rwanda soon after the collapse of the UN operations in Somalia, where US troops had been killed, and dragged through the streets. The countries had become so risk averse, that they were not about to jump into another situation which reminded them of Somalia. Instead of increasing the numbers, we scaled back.

In those situations, governments look after their own. So the question of protecting the Rwandans was secondary.

So is national interest the only reason countries actually go to war or does moral justification come into it also?

There is a lot of pressure on the political leaders who have to take these decisions when it comes to intervening morally in conflicts. There is also yes, the number one question that countries always ask: what is our national interest? Or as Americans would put it quite bluntly: do we have a dog in this fight? And so you cannot get away from the national interest, but that does not mean that because we cannot intervene in every situation, we should not intervene where we can.

Why have you maintained the conflict in the Darfur region was not genocide?

The UN sent in a commission to Darfur, headed by Antonio Cassese, who was a prominent Italian judge. They came up with a report, confirming there was systematic abuse of human rights, and to some extent, crimes against humanity. However, they could not determine after their study, that it was genocide. That would entail judicial determination, and analysis, so the commission stopped short of calling it genocide.

This was a report that went to the Security Council. It was on the basis of that report that the Security Council referred the Bashir case to the International Criminal Court. Having accepted their report, I couldn’t say it was genocide. I had to accept the judgment headed by Cassese.

Even though the Americans then called Darfur a genocide, they didn’t change their policy. They declared it genocide and did nothing.

When do you think the outdated model of the five permanent seats on the Security Council of the UN will change?

Change should come, when I cannot say. Access

I tried very hard to bring about change, to see if we could create permanent seats for Latin America, Africa, India, and Japan, but we did not succeed. This would have made the Council a bit more democratic.

The pressure is becoming even greater with the emergence of the new powers, such as India, Brazil, Indonesia and other countries. They would expect to have a voice and a place at the table. It will be in the interests of the organisation to have them there. So these reforms cannot be resisted forever.

Why do you think governments in the West initially don’t engage in discussions with terrorist organisations such as al-Qaeda, the IRA, or Hamas, and then do so in the end?

There are two reasons. Firstly, you have to discourage people from becoming terrorists, and secondly, you don’t want to give them recognition, or respectability in a civilised and stable society. But you come to realise they are a reality. You have to deal with them to bring peace. We have seen this in Northern Ireland, and in other places. In the end, you have to talk. The same thing will have to happen in Syria.

Do you believe the word terrorist has connotations that might be reductive?

It is a word that has a meaning, but it also has political connotations. One man’s terrorist is another man’s freedom fighter. But terrorism has real meaning. The use of violence is not something that one should encourage or support. Regardless of one’s cause, we have to be careful not to get into violent action. We need to try and dissuade them to use other means of solving their problems. Terror that strikes fear into the population, as a means of achieving one’s objectives is not something one should support and encourage in civilised society.

In your book you argue that by the 1990s the UN had forgotten the first three words of the UN Charter, which were written in June 1945: ‘We the Peoples.’ Why did you believe this to be the case?

The UN is an organisation of states. It was put together at a time when the sovereignty of states was very high on the agenda. But when I was doing some hard thinking about this, I went back to the phrase, ‘We The Peoples’, because in the end, that phrase was intended to protect the ideals for which the UN stands for. When we talk of sovereignty, it should be seen as a structure intended to avoid wars, to protect territories, for each one to take control of their area, and ensure that peace prevails.

You have negotiated in the past with Saddam Hussein, Omar Al Bashir, and Muammar Gaddafi. Do you believe it’s worth taking the pragmatic approach with tyrants to achieve peace?

Whether we like it or not they exist, they have power and influence over their people, and are the ones we have to deal with in the situations we are trying to correct. How do you get them to change by not engaging them? Sometimes you need to talk with these people to save lives, and to stop the gross abuse of human rights. You need to try and find a way of getting them to understand, because you cannot go and blast your way in. I’m a diplomat, not an army general with a whole brigade behind me.

General News of Friday, 30 January 2015

Source: starrfmonline.com

Kofi Annan talks about growing up in Ghana, terrorism, Rwanda genocide

Entertainment