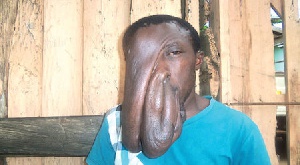

The first time Weekend Sun stumbled upon Tanimu Nuhu, hearts stalled. He instinctively raised his hand to his head, and then to his heart. A low gasp escaped involuntarily from his lips. The moment was stirring.

You may never meet anyone like him, ever, in your life. He looks like a character who just jumped off the movie set of ‘Stars Wars’; alas, Tanimu lives with his siblings in Kwabeng in the Eastern Region. It’s impossible to miss him anywhere; he is so different he stands out.

Tanimu Nuhu, 28, suffers from a rare genetic condition known as Facioscapulohumeral Muscular Dystrophy, or FSHD for short. This extremely uncommon medical condition has caused excessive growth in his facial muscles. It has completely disfigured and distorted his face. It has also muffled the sound from his voice; when he speaks, you can hardly hear him. His lips have grown into a snout that hangs limply over his chin.

The condition of FSHD is congenital. Nuhu was therefore born with it.

Narrating how it started, his older sister Hajia Fati Nuhu recounts:

“When he was born, we noticed a tiny blob on the tip of his right eyelid, what we commonly call dehyea in Twi“.

The almost insignificant sty grew until it covered his right eye. Even at that early age, the pain tore at him relentlessly. His battle to lead a normal life had begun.

His medical history is a moving chronicle of one person’s defiant battle against an illness that has eclipsed him all his life.

When his late father Nuhu Adamu realized the monstrous growth wasn’t going to go away, he sought the intervention of pediatricians at the Agogo Government Hospital. The lead surgeon there advised against an early surgery; he asked for more time to study the cause of the disfigurement. An adamant Adamu however persisted and little Tanimu was laid under the scalpel.

When Tanimu was discharged, his family was very hopeful. There was no sign of growth on his face then. It was too early to savour any victory however. Every day, they would turn his eyelids inside out, watching for any signs that the malignant growth was coming back.

It came back. Not long after they returned home, it started growing again, this time with a ferocity that signaled the onset of a fresh stage of growth.

Tanimu’s condition has hounded on him all his life; in school, his eyes would mist over, clouding his vision. His classmates, loving as they were, couldn’t bear the stench his constantly salivating mouth gave off so he had to drop out in Class Three. He has not been able to continue.

Watching him take his meals, it would hit you with sudden force what a privileged act eating is. For Tanimu, every meal is an arduous task. The excessive growth has fallen into folds of thick skin over his mouth and totally obscured it. To reach his mouth he has to lift up the folds and hold them while he slips morsels of food inside.

His ordeal doesn’t end there. Chewing is painful and he has to patiently move his molars. He feels a clang in his head when his teeth clash against each other. When this happens, he has to endure hours of biting headache.

Tanimu lives with some of his siblings in the town of Kwabeng, a sleepy town nestled beneath the mountains and forests of the Atiwa range in the Eastern Region. During the dry harmattan season the taxi drivers fancy themselves as Grand Prix racers. Wearing fatigues of blue jeans with sleeveless tank tops they speed their way on the dusty untarred road to town, bathing pedestrians in red dust.

Tanimu’s family, and members of the Zongo community where he lives, supports him all they can. When he reached adolescence he found it difficult to go out with friends. Anytime he did, he would wrap his head in a turban. The larger community was alien to him. Tanimu was the man with no face.

He stopped using the turban when his friends encouraged him not to hide behind the mask.

It is late morning and the sun is climbing high. Tanimu sits like a wraith: silent and sullen. He is resting on the long wooden bench made from bamboo in front of his family house. He is shaded by a tree. Close by sits his childhood chum Abdul Karim. Karim is a contracted excavator operator who works with one of the mining companies in the community.

They talk together. Karim has to sit on Tanimu’s left side because the man with no face can only hear through his left ear.

“I have been close friends with Tanimu since childhood so his disfigured face doesn’t worry me anymore.

When people see him for the first time they can’t help staring at him. It is terrible. Babies and children are scared of him. When they see him, they run away screaming,” he said.

Tanimu likes sitting on the long bench to while away time. Otherwise, he stays indoors to watch movies.

“I used to sell eggs until a few weeks ago when I lost everything. Now I sit on this bench outside. I watch the cars passing by, thinking about how the people inside are going about their activities. It helps quell the rage inside me,” he told Weekend Sun.

“A lot of the time he watches local Ghanaian and Nigerian movies,” volunteers sister Fati. “I guess it is a kind of therapy for him. He gets to know he is not the only person with troubles.”

Acceptance doesn’t come easy. Even now, Fati reveals, he exhibits suicidal tendencies. She would often find him huddled in his room. With his knees drawn to his face he would sob for hours on end.

She says those tears rend her heart. With counseling he is gradually coming out of the occasional depression that assails him.

She says those tears rend her heart. With counseling he is gradually coming out of the occasional depression that assails him.

It isn’t difficult to fathom why Tanimu is tempted to end his life. It’s almost impossible to observe without envy when most of your cohorts are happily married, bearing children and engaging in fruitful employment.

Sometimes he feels that familiar natural longing in his loins and the heat gathers between his thighs. He wishes he would take a woman. It is an elusive dream because no maiden would submit herself to him.

Ramatu Abdul-Razak, 20, is one of Tanimu’s female friends and lives a few compounds away. She has known him all her life. She has completed her apprenticeship and most importantly hasn’t been betrothed.

“I hope to marry soon,” she says. Then, she smiles demurely. “But not from here,” she confides. Her statement is an insinuation. Like most of her friends who are married, she has spent all her life in Kwabeng. Where else would she marry from? It is nine out ten she would settle with a young man from here. What she means is “I’ll marry from anywhere there isn’t a Tanimu.” Ouch!

“When I had my aworre (Muslim marriage ceremony) about three years ago, Tanimu came. He didn’t cry but I knew he grieved inside,” Karim remembers.

Taminu’s condition is akin to that of Sam Lightener in the United States. As a boy, Lightener had developed a rare facial growth known as vascular anomaly. He had it from birth, just like Taminu. That is where the similarities end. Lightener’s parents were middle-class working professionals who had medical insurance cover. They could afford the huge medical bills that accompanied his treatment.

Eventually Sam Lightener was operated on by a team of surgeons at the Boston Children’s Hospital (the operation lasted thirteen hours). Can Tanimu hope for similar help? Taminu’s father Nuhu Adamu was an illiterate vagrant farmer who also traded in cola nuts; his mother was a housewife who died from grief over her son’s illness when he was six years old.

He has been dependent on benevolent members of the community who are saddened by his affliction. The recently deceased Gyaasehene of the Akyem state and chief of Kwabeng Nana Daasebre Owura Nkwatanbisa II sponsored a surgery at Korle Bu Hospital. The growth seemed to recede, only to recur. The management of a local mining company, Xtra-Gold Limited also funded a surgery at the same hospital.

Tanimu is 28, and yet his illness has left him diminutive in stature and stunted in height. He looks like a student in primary school. His many hours of solitude have made him reflective and attentive to the needs of others. He spends a lot of his time reading the Koran. This is because he finds sleep difficult. He has to toss endlessly before sleep gives him temporary respite from his pains. This has made him a ready counselor to his friends. They have nicknamed him ‘Alpha’, a Mallam.

Tanimu sits on the long wooden bench outside his family home. It is the same scene today as it has been for the past few years. The cars and lorries shuttle and whizz by. There’s a ramp so they slow down. In the vehicles heads turn and notice him.

Shock. Pity. Fright.

“I hate it when people stare at me. I want to yell at them to stop. Imagine what would happen if I begin to feel sorry for myself. Already my family is burdened so much,” Alpha Tanimu says. Every day, he feels as if the growth is an unseen enemy; it is keeping him out of his own life.

“But I plan to make something of myself,” he assures.

Tanimu’s stoic determination is inspiring. He still hopes he can become a teacher and pour his life into future leaders. Right now, he needs a face and he wants it urgently.

General News of Monday, 8 December 2014

Source: Weekend Sun Newspaper