Obituaries tend to do good public relations for dead people.

As far as this allegation goes, I make no promises of the distinctness of my remembrance of the departed former Ghana president, Jerry John Rawlings. It is hard not to be reminded of the complexities of his legacy and the fact that perhaps, more than Kwame Nkrumah, Rawlings was for better and worse, the most consequential leader of Ghana.

My familiarity with the man seeped through delicate family history. On one side of my family, my mother’s, there was the incident after 1981 when my maternal grandmother, a burgeoning market queen, lost her stores in Accra’s commercial business district due to the extreme militaristic method of the Rawlings-led Provisional National Defence Council’s (PNDC) ‘cleansing’ of the system. During this purge, every man and woman of means was looked at with enough suspicion that all but confirmed guilt.

Market queens were a powerful few in Ghana’s urban centers after independence. Face2Face Africa‘s recounting of how Nkrumah became married to an Egyptian belle by the name Fathia Rizk illustrates how the first president of Ghana tiptoed around the issue of preferring a “white woman” in order not to offend these women who were financiers of Nkrumah’s Convention People’s Party (CPP).

Rawlings called this period of undoing the power of the moneyed class, a revolution. In his narrative, this was when “the people” rose up against the moral decadence of the merchant-cum-lawyer-cum-political class. Other factors also softened the ground for this revolt especially as the country was unable to withstand famine as a result of drought and the economy was on its knees due to the withdrawal of support from both the powers of the east and west.

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) file that detailed the beginning of Rawlings’ rule as a military leader interestingly noted that the Soviet Union was not sold on Rawlings’ credentials as a leftist “hence declined to commit substantial amount to an unstable regime”. In that time of the Cold War, lacking the seal of Moscow looked strikingly like the Pope calling you un-Catholic.

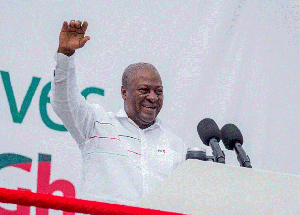

Yet, this was a man, with enough charisma to light up the Eiffel, mounting stage after stage in Accra in his military jumpsuit rallying the people on the need to bring the enemies of the people to book. He was a captivating speaker who drew everyone from professionals to school kids to his rallies.

Wealth redistribution was the only thing on his agenda for Rawlings believed, perhaps until death, that there was something fundamentally immoral about the state of a hungry working class. Unlike military dictators you may be familiar with, Rawlings was an adequately educated military officer whose pull towards populism was not as ideological as it was pragmatic.

1981 was Rawlings’ second attempt at seizing power. In 1979, he did seize power, lost it and was imprisoned along with the co-conspirators from the Armed Forces Revolutionary Council (AFRC). However, on June 4 of that year, Rawlings was freed by a collection of junior army officers after it had become apparent that his trial had actually made him nationally popular.

At his trial, Rawlings said these words that have become etched in the memories of Ghanaian common folk:

“I am not an expert in economics and I am not an expert in law but I am an expert in working on an empty stomach while wondering when and where the next meal will come from. I know what it feels like going to bed with a headache, for want of food in the stomach.”

And so for the avoidance of doubt, this was no Maximilien Robespierre possessed by the ferocity of seeking justice. Rawlings did not grow up well-to-do and it is believed that he might have never met his Scottish father who took his Ghanaian mother as a mistress. Rawlings lacked the backstory of grandeur.

In both the short-lived coup of 1979 and the 11-year long reign after 1981, there were a lot of casualties from the determined cleansing exercise. There was the tendency to rope in innocents like my grandmother who I have come to believe, into a cluster of suspected hoarders, racketeers and extortionists whose efforts had set up a system of perpetual profiteering.

A considerable number of Ghanaians resident in Europe and America today are offspring of the business and political elite who escaped the wrath of Rawlings. He was a man with an answer and he was seeking questions and taking no prisoners.

The extra-judicial killing of three judges, two of whom were Supreme Court justices, in 1982 has become the sourest lingering taste from this era. Rawlings always insisted that he had not ordered those killings and bowed to public pressure to have the murders investigated.

In spite of all of this, the myth fanning the flames of Rawlings’ greatness endured. He had earned the nickname Junior Jesus, due to his initials J.J., and he was the one to lead the suffering masses out of the misery orchestrated by those on whom he had set his unforgiving gaze.

My mother’s family felt powerless in this period. There was little to no room for recourse to justice as the anti-rich sentiments overwhelmed the need to err on the side of caution in this crusade. What had been taken was gone and never to be recovered.

Growing up, I believe I remember my mother at several points in conversations, forcing into her submissions the logical extensions of “what if I had inherited two stores from my mother” in one of West Africa’s most commercially vibrant locations? I have never been able to tell if these hypotheticals save her the tears or whether she was mourning the circumstances that have mitigated her current rather respectable successes.

By the middle of the 1980s, the list of rich people to blame was getting shorter for Rawlings and the PNDC. The “holy war”, as he had called it, was lacking adversaries and after nearly a decade, his government had become the establishment. The campaign for wealth redistribution had spectacularly failed, not necessarily because of mismanagement, but because Junior Jesus simply had no five loaves and two fishes – Ghana had been broke for a while.

This is where, for many, Rawlings stood out among dictators. Surrendering to the Bretton Woods institutions as well as western donors for help came with caveats that loosened the intensity of Rawlings’ grip on the country. This was the period of structural adjustments that liberalized the Ghanaian economy and set the country upon the path of slow, unequal but certain growth.

This period was also the point where the vociferous egalitarian’s edge was blunted by the money and comfort that came his way too. After 1992, one of the most contentious issues in Ghana was how rich Rawlings and his family had become.

But something else happened before 1992. Rawlings took this breath of new life to implement the agenda of Ghana’s renaissance. I have made the point prior to this piece that it is undeniable that Rawlings is the father of whatever we can call modern Ghana.

The renaissance required an admission that soldiers had to give way to technocrats. By the time the PNDC was disbanded in 1992, it comprised more civilian administrators and professionals than war-ready soldiers. This was very significant because it was a rarity on the continent for a military government to allow so much input from civilians.

My paternal great-grandfather, Ebenezer Cephas Quaye (EC Quaye), who had been the first post-republic mayor of Accra and a personal aide to Nkrumah, was consulted by Rawlings several times on nation-building strategy prior to 1992 and afterward. Rawlings sought his wisdom on phone and from our family home in Accra and upon invitations to the Osu Castle, the seat of government at the time.

Some of the things they would discuss include EC’s support for the National Democratic Congress (NDC), the political party Rawlings founded when the PNDC restored multiparty democracy in Ghana in 1992. EC never openly supported the NDC, choosing to remain a Nkrumahist till death.

I was a personal favorite of EC’s and as a little boy of not more than six, I was granted a child’s access to his meetings with some high-ranking government officials after 1992. I have very concrete memories of the visit of Nii Okaidja Adamafio, one time a Minister of Interior, as well as of Paul Victor Obeng, one of the longest-serving heads of Ghana’s investment promotion center.

From hindsight, I have picked up two effectively marriageable versions of the same man. From my maternal family, I have learned of Rawlings, the murderous destroyer of futures and fortunes. From my father’s, I have come to know Rawlings as the man who had a reason to destroy and rebuild from scratch, listening to wisdom as he set one brick upon another.

Both versions are true. I do not know how I could understand that one man was both things but I did.

I would like to believe what has made it easier for me over the years, was the abundance of similar stories as my grandmother’s as well as the effect EC’s intimacy with Rawlings and his people had on me. Nowadays, when I am now capable of independent critical historical perspectives, I have found more refined ways to believe what I have always believed.

One has come to learn of Rawlings’ role in maintaining a Ghanaian contingent, the only contingent at all, in Rwanda when the United Nations feared the worse prior to the genocide in 1994. And of his desperation and efforts to have the likes of deadly Liberian leader Charles Taylor and his Sierra Leonean counterpart Foday Sankoh removed from power in the late 1990s. And of the fact that he fiercely plugged Pan-Africanism wherever he could and to the delight of Muammar Gaddafi and Nelson Mandela alike.

Posterity will come to give him a balanced view, I hope. And may it come to the conclusion that J.J. was the Nietzschean man who may have stared too long into the abyss at certain points, at least.

Click to view details

Opinions of Friday, 20 November 2020

Columnist: face2faceafrica.com

Remembering Jerry John Rawlings: The best of the worst

Opinions