In Nigeria (and Ghana), the simple act of popping a pill can be life threatening.

Will the medication be what it says it is, made by a reputable company? Or will it be a clever copy that looks virtually indistinguishable, but contains a sugar pill at best - or, at worst, something like the tainted teething syrup that killed at least 80 babies in 2009?

Although no one knows the full scope of the problem, one study found that 35 percent of malaria drugs in Nigeria were fakes, and others suggest that counterfeit medicines are rampant across the developing world, including in India, Ghana, Kenya, Tanzania, and parts of South America.

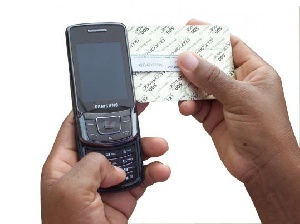

Sproxil Inc., based in Cambridge, is helping customers in those countries distinguish genuine medicines from fakes. Using a system it calls mobile product authentication, Sproxil allows customers to text a number on the package to confirm or refute the drug’s authenticity. The process “is designed to use the abundance of cellphones to empower the consumers to avoid purchasing fake products,’’ said company founder Ashifi Gogo. “This way, they can reestablish trust between the consumer and the pharmacy.’’

The drug manufacturers who hire Sproxil agree to embed on each package a scratch-off panel, like those used on lottery tickets here and on prepaid cellphone cards in much of the developing world. The customer types in the code revealed by scratching the panel and sends it via a free text message to a Sproxil line. An almost immediate response indicates whether the medicine has been manufactured by a reputable pharmaceutical company or is a fake.

“This is a hugely innovative idea that we think could be a real game changer in terms of how pharmaceuticals are delivered,’’ said Shuaib A. Siddiqui, a portfolio manager with Acumen Fund, a New York nonprofit that invests in companies providing services to the poor in developing countries. “This can really ensure that the poor are getting access to quality drugs.’’

Acumen invested $1.8 million in Sproxil this year on the strength of its idea and the relationships that Gogo has been able to build with major international drug companies, including Johnson & Johnson and GlaxoSmithKline, as well as pharmacies in Nigeria, Kenya, Tanzania, and elsewhere.

Gogo, a native of Ghana who received a PhD from the Thayer School of Engineering at Dartmouth College, said he was moved by the magnitude of the counterfeiting problem.

“For tuberculosis and malaria alone, up to 700,000 people die every year due to fake products,’’ he said. “That’s four jumbo jets full of people dying every day.’’

Gogo developed the technology as a class project while at Dartmouth. He first tried to use it to help customers at Whole Foods determine if their produce was genuinely organic. But he was surprised to learn that Whole Foods customers trusted the store to supply authentic products. So, he set out to find a situation where there was no trust between customers and suppliers.

As a shopper, it is nearly impossible to distinguish clever phony drugs from the pharmaceuticals they mimic. The sham products often look better than the real ones, Gogo said, because the forgers’ factories are newer and their profit margins higher. But the ingredients are often different.

“These fakes contain anything from chalk to road paint and all sorts of things that shouldn’t be in pills,’’ Gogo said.

Gogo’s aim is to empower customers to identify and refuse fakes, so suppliers will not want to offer them. “If enough people won’t buy the fakes, the pharmacies won’t buy the fakes,’’ he said.

Sproxil’s first efforts were in Nigeria, where the government was reeling from the teething syrup scandal, in which the syrup was laced with ingredients found in antifreeze, according to newspaper reports. Based on government introductions, Gogo was able to meet the right people in industry and get Sproxil’s scratch-off panels onto products across the country. Success there led him to other countries.

Ethan Zuckerman, a member of Sproxil’s advisory board and director of the Center for Civic Media at MIT, said the power of Gogo’s idea is that it is so easily transportable.

“It meets local needs not just in one country, but in much of the developing world,’’ said Zuckerman, who has worked on technology development in Africa for more than a decade. “He’s been able to take this out of the realm of theory and into the realm of practice in a really successful fashion.’’

General News of Monday, 26 September 2011

Source: .boston.com