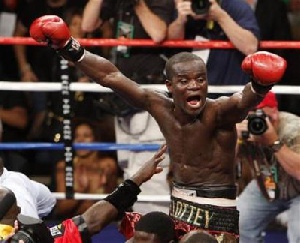

The Ghanaian Joshua Clottey overcame long odds to reach his bout at Cowboys Stadium against the W.B.O. welterweight champion, Manny Pacquiao.

By GREG BISHOP Published: March 12, 2010

ARLINGTON, Tex. — Even here, with Saturday’s welterweight title fight in Cowboys Stadium, with nearly 45,000 seats sold, with Manny Pacquiao defending his latest world championship, the fight that fell apart looms over the proceedings.

Every day, someone asks Freddie Roach, Pacquiao’s trainer, about the other fight, the dream bout between Pacquiao and Floyd Mayweather Jr., boxing’s undisputed kings. Roach gets that question in grocery stores and shopping malls, from Magic Johnson and the celebrities who train at his Wild Card Boxing Club, even from a waiter at an ice lounge in Los Angeles.

“I was wearing an Eskimo hat,” Roach said. “Same question. Everybody wants to see that fight.” Instead, Pacquiao will face Joshua Clottey under the most jumbo of all JumboTrons, in the fight few wanted except for the participants, none more so than Clottey. To get here, he survived poverty in Africa, career turmoil and four years spent out of boxing, all to become the latest challenger from the most unlikely of boxing hotbeds.

Pacquiao travels in a luxury bus with his image plastered on the side. On Thursday, Clottey rode to Cowboys Stadium in a hotel shuttle van. Pacquiao houses his sizable entourage in two homes in Los Angeles. Clottey lives in a one-bedroom apartment in the Bronx.

Clottey lives a simple life, born out of necessity, buoyed by boxing, each of his 32 years defined by struggle and by spirit. “I have the mentality of a warrior,” he said. “I love to be in the ring.”

Clottey grew up in Accra, Ghana, a place he described with two words: small and poor. His father worked in road construction, earning barely enough money to care for six children and Clottey’s mother. Clottey grew up in a house with one room. As many as 10 people stayed there at a time, sharing a single bed, sleeping in shifts.

Clottey, part of the Ga tribe, grew up in a neighborhood called Bokum. He said the Ga fancied themselves as warriors, and that translated naturally to boxing. “There is no help from nowhere,” Clottey said. “That makes you a harder boy. You have to be hard. Because if you don’t do that, you’re not going to eat.” Boxing reigned in Bokum, like football in Texas or basketball in Harlem. Except, instead of pickup basketball, the boys in Bokum had pickup boxing.

Clottey said his neighborhood was split into seven areas, each with its own gym. He used the word “gym” loosely, because fights often took place on concrete, inside a thin rope, without hand wraps and with torn, mangled gloves. “Like there,” Clottey said, pointing to a dilapidated parking lot.

From this warrior mentality sprung dozens of warriors, the modern-day kind who fought their battles inside makeshift boxing rings. All the fighters — from the featherweight champion Azumah Nelson to the bruising welterweight Ike Quartey, among others — came from this small, poor place.

Many boxing champions have risen from similar circumstances, but the concentrated volume made Bokum different. Boxers became the area’s chief export.

“Manny Pacquiao’s poverty makes an American kid’s poverty look like luxury,” said the promoter Bob Arum of Top Rank Boxing. “From what I’ve heard, Clottey’s poverty makes Manny’s poverty look like luxury.”

Throughout his career, Clottey carried with him the spirit from the neighborhood. He endured a disastrous stretch in England, where he said he never faced top competition. He returned to Ghana, where he began plotting his big break — which was available only in the United States.

He arrived in 2003, broke, and landed in the Bronx, minutes from Yankee Stadium. The first time his manager, Vinny Scolpino, watched Clottey spar, Scolpino had never so much as heard of him.

“I didn’t know him from a hole in the wall,” Scolpino said. “Joshua Clottey was nobody, basically, just another 10-round fighter. I always thought he had something, a spark. Maybe because he had so little, he needed something.”

Clottey compiled a 35-3 record, with 21 knockouts, and his losses came against world champions. He beat Zab Judah. He lost by close decision to Antonio Margarito, despite fighting with a pair of broken hands. In his most recent fight, last June, he lost by controversial split decision to Miguel Cotto.

None of those fighters knocked Clottey down, or cut him, or left any mark other than three losses on his record. The only mark on Clottey is the tattoo he had inked a few weeks back, his initials interlocked with boxing gloves on his right forearm.

Roach predicted Pacquiao would become the first fighter to “stop” Clottey, to end the fight before the scorecards are tallied. Clottey responded: “Why would Manny Pacquiao knock me out? That surprises me. He can’t knock me out with punches.”

After the Cotto fight, Arum consoled an emotional Clottey in the dressing room by promising bigger future fights. Neither Scolpino nor Clottey envisioned what came next, when the Mayweather negotiations fell apart because of blood testing and Clottey landed the biggest of all bouts.

All week, these fighters tossed compliments at each other. Pacquiao called Clottey a gentleman and a “nice guy.” Clottey, while vowing to attack the smaller, quicker Pacquiao, lauded his place in boxing history.

Scolpino believes his fighter can shock Pacquiao on Saturday. He pronounced Clottey to be in the best shape of his career and said, “If he comes out with a ‘W,’ man, he’s on top of the world.”

If Pacquiao wins, and Mayweather defeats Shane Mosley on May 1, negotiations are expected to resume for the fight that would transcend boxing. But first, Pacquiao must topple Clottey, a fighter familiar with long odds.

“People have lost sight of Clottey because of the Mayweather stuff,” Arum said. “He’s never had the exposure. He’s never been a network favorite. But people who say this is going to be a walk in the park for Pacquiao are crazy.”

Inside Cowboys Stadium on Thursday, Clottey leaned forward in the stands, his eyes fixed on the scoreboard that read “Pacquiao-Clottey, The Event.” Clottey had secured the fight he always wanted.

For him, Mayweather-Pacquiao could wait.

Sports News of Saturday, 13 March 2010

Source: NY Times