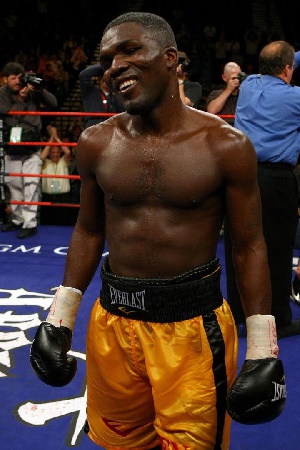

The gates to Ben Tackie’s home show just how much he loves the sport. They are shaped like conjoining boxing gloves – an art piece that makes you wonder how long it took the smith to put together.

His living room, littered with photos of a time when he quietly knocked down fighters, shrugged off the underdog tag and shocked many.

At the rear end of the living room, there is a case – occasionally moved from its position – that contains his most important belt. It is a North American Boxing Federation Light Welterweight title he won from Ray Oliveira in 2001. That fight is listed amongst Tackie’s greatest in the ring. It produced 2,729 punches and sits third on the all-time list of the most punches in a bout.

On arrival at his home in Gbawe, a few kilometres west of the city centre, he stood in his upper balcony with elbows perched on its parapet, shouting orders down below to his nephew, who is training to become a boxer.

But the man has not changed. He still has his calm demeanour and is still a collected gentleman but strangely quite different from the boxer we watched for 21 years from 1994 to 2015.

Tackie didn’t want much. He wanted a better life. A life better than the one he had back in the fishing slums of Chorkor, where he would go fishing for days before he could eat.

His dad had abandoned his mum when he was 6, so he had to be a man from the off.

“When my daddy left, I had to be a man. I went to school for a few days and decided to quit to help my mother. So I started fishing. Every morning I go to the seaside with the big guys,” he reminisced with his face painted with layers of nostalgia.

He had a tough childhood and he dealt with it all with such equanimity and class.

Tackie’s path to becoming a boxer did not follow the trajectory of the quintessential Ghanaian boxer.

Many Ghanaian boxers begin in their early years. Childhood fighters, then to the amateur level where it is the most challenging to becoming a professional.

But in Tackie’s case, he was older by the time he decided to take up boxing as a full-time job.

There was no time to go through the long and winding foundry of amateur boxing. He started at the Black Panther gym with boxing mates Joshua Clottey, Emmanuel Clottey and Isaac Tetteh, whom he beat in his final fight in Ghana in 1997 before heading to the US, in Bukom under the guidance of boxing trainer, Emmanuel Teiko Tagoe and connoisseur, Ray Quarcoo.

Quarcoo was one of the finest names who took boxing to a different level in this country.

“Everything happened like magic. That’s why my late coach named me ‘Wonder’. Because I used to be a fisherman. My grandmother was a fishmonger; my grandfather was a fisherman. All my people are from the fishing side. So how can I say I have any regrets. Boxing helped me big time. Boxing made me who I am today.”

It is the sort of gratitude to the sport that makes it so great. Several boxers the world over have shared similar sentiments about it in this manner.

The boxer’s welcome into professional prizefighting felt like a carpet had been rolled in his way.

He won his first 18 fights – sweeping aside Jimmy Gerald, Hicklet Lau, Edwin Santana and Jose Luis Montes.

But in 1999, he was stopped in his tracks by Gregorio Vargas, a fight he still rues till date. The ramifications of it have been heavy on the man and it was one of the topics he did not enjoy talking about.

The devastating defeat that was so damaging to a fledgling boxing career was filled with foreboding long before the opening bell of that encounter. Money was a factor but it didn’t have to.

“I wasn’t ready. I am going to give excuses. There’s no way I will give an excuse for any fight I have in my life. When I lose, I know I have lost. I wasn’t ready but the money was good. I hadn’t heard $20,000 in my life before. All I was fighting for at the time was $3,000 and $2,000. I had to take it.”

He answered with a regrettable look on his face.

‘Wonder’ was a pesky, “in your face” sharp combination puncher who believed in coming alive in the closing rounds. At some point in his career, they called him the comeback king, a moniker he got after knocking down Edwin Santana and Freddie Pendleton who had their names in winning positions on the judges’ cards but managed to win with a knockdown late on.

In 2000, in the crucible of a toe-to-toe match-up with former IBF light welterweight world champion Roberto Garcia, Tackie showed his class.

The Ghanaian was losing 83-87 on the cards but somewhere in the cauldron of the 10th round, he found his mojo.

His left hook spun Garcia’s head in its axis and it was game over. That fight was a textbook boxing clinic.

“For Roberto Garcia, I watched his fights and when we got the shot, I looked at him and I said wow he is a former world champion. At the time I was well conditioned. So I knew I could do something. I said listen, this guy has speed so I am going to give him 5 rounds. After 5 rounds, I will make sure that the last fight rounds, I am going to knock this guy down. If I don’t knock him down, they are going to give it to him. So I will knock him down”.

That knockout won Tackie Ring magazine’s knockout of the year.

“It was an exceptional feeling when I heard it. My name is in the history books. I won titles but this one makes me very happy,” he said gleefully.

Tackie’s record reads 44 fights, 31 wins, 13 losses and 18 knockouts which is a pretty decent record. A chunk of the losses was recorded after the fight against Kostya Tszyu in May 2002.

After that fight, he stacked up 7 wins in 17 fights including a fight with the legendary Ricky Hatton in 2003 before he hung up his gloves in 2015.

Ghana’s over-achievements in boxing makes Tackie’s career look mediocre but he showed everyday why any boxer needed to be cautious when he was in the ring.

“I sit down and watch some of the fights sometimes and ask myself why. Maybe I could have done things differently but that’s just how it is. Sometimes things don’t go your way.”

Now, he lives the most part of his life in New York where he works as a security person. In his free time though he goes on to teach young boxers some skills. Boxing is certainly his life.

For some people, tradition is a path to glory. For others, it is peer pressure from people who have walked in their shoes but for Tackie, it is a means to rewrite his family’s legacy. Wonder!

Click to view details

Boxing News of Sunday, 29 November 2020

Source: 3news.com