Three weeks ago, Badamasi Mohammed left his wife and two children in Maradi, Niger’s second-largest city for a trip to Kano, about 300km away (186 miles) in northwestern Nigeria.

But since August 5, the 30-year-old freight truck driver has been stuck like more than 20 other trucks, at the Jibiya border post in Katsina, the state linking Kano to Nigeria’s French-speaking neighbour.

Nigerian authorities at the border have denied him re-entry to his home country because of existing sanctions on Niger after a July 26 coup that led to the overthrow of Mohammed Bazoum, the latter’s president since March 2021. The Niger coup plotters also shut their borders after the coup.

In the last seven days, Mohammed’s truck, parked at the border has become a bathroom, bedroom and walk-in closet, and multipurpose facility for him and his two assistants. His boss in Maradi has had to send money through bureau de change operators to the bank account of a point-of-sale attendant in Jibiya who then paid cash to Mohammed.

And the situation is taking a toll on the driver, who, as breadwinner for his family, who cannot earn the 40,000 CFA ($67.25) he used to make on average per freight. His only consolation is that he left enough food back home for his family to survive on.

“I am not happy being away from my family, I am tired of being here,” Mohammed told Al Jazeera. “Each time I speak to my family, they always ask if people are being killed over here. They are not happy,” he said.

Landlocked Niger shares borders with seven African countries but the 1,600km-long (994-mile-long) border with Nigeria, Africa’s largest economy, is arguably its most important. More than a million people live along this stretch of land, and have shared commercial and cultural ties for centuries. Most of them are Hausa, the largest ethnic group in both countries.

The aftermath of the July 26 coup is now testing those ties as its effects spill across the borders from Niger, where life has also changed for everyone.

A flurry of sanctions

Bazoum’s election was the first civilian-to-civilian transition in Niger since its independence in 1960 and in two years in office. His detention by members of his presidential guard and subsequent removal was the seventh coup across West and Central Africa in three years.

The coup also hurt the image of a country once seen as a reliable ally for the West in the Sahel, a region blighted by expansionist armed groups linked to al-Qaeda and ISIS (ISIL).

ECOWAS convened an emergency summit to determine an appropriate response.

The 15-member regional bloc swiftly imposed sanctions on Niger including the closure of land and air borders and giving a seven-day ultimatum to the coup leaders to reinstate Bazoum or face the potential use of force.

Multiple Western countries also cut funding to Niger, one of the largest by landmass – yet poorest – countries in the world, which relies on external aid for up to half of its budget.

Niger, the largest recipient of foreign in West Africa after Nigeria, received $1.8bn in aid in 2021 alone, according to figures from the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

So far, the coup leaders have defied them and the bloc, rallying support in Niamey, the capital even on August 6, the day the ultimatum expired. A 21-person cabinet was also announced late on Wednesday by the coup leaders on the eve of another summit by ECOWAS.

At the grassroots, the impasse is already affecting Niger’s 25 million people, half of whom live below the poverty line earning less than $2.15 a day.

Nigeria also cut the power supply to its neighbour, which depends on it for as much as 70 percent of its electricity. And food prices, already on the rise because of complications in global supply since the Russian invasion of Ukraine, have risen yet again.

The post-coup sanctions and cessation of subsidies could hurt a country struggling with food security and one of the worst ratings on the human development indices in the world, experts said.

Mihidi Ameride works as a field officer at Projet Filets Sociaux (Safety Net Project), a project funded jointly by the World Bank and the Niger government.

His project caters to vulnerable and rural populations in 40 Nigerien communities through cash transfers and a cash-for-work (CFW) scheme. It also supports women artisans and keeps girls in school through scholarships.

Now that the World Bank has suspended aid to Niger, 66,000 households will be affected when the project ends, Ameride told Al Jazeera.

“There is great concern about the food security of populations subject to robbery, banditry and … personally, I’m affected, because my life depends on the sustainability of the project. It’s the only thing I do for a living,” Ameride said.

“I’m all for democracy and a coup d’état is not a good solution for an already poor country like Niger.”

The bloc also imposed sanctions on Guinea, Mali, and Burkina Faso, but lifted them later. The three nations have remained under military rule, and there has been a growing sense among international observers that sanctions were not working as a deterrent across the region.

“[The] junta will also be well aware that in neighbouring Mali and Burkina Faso, similar sanctions were also applied in the immediate aftermaths of coup d’etats but were later rescinded after these junta governments disclosed a transitional timetable and released all imprisoned politicians,” said Ryan Cummings, director of analysis at Johannesburg-based Risk Signal consultancy.

“It is tough to say that the sanctions are working [to end coups],” he added. “If anything, their application has emboldened the CNSP putschists who are undertaking mechanisms to entrench their rule, particularly in terms of creating a government with civilian inclusion so as to purchase this dispensation some legitimacy.”

Still, the effect of the sanctions could lead to significant inflationary pressures which will affect the country’s population, since Niger lacks the fiscal leeway to offset these cost-of-living pressures over the near-to-medium term.

‘No one is happy’

Back at the borders between Nigeria and Niger, both countries are fully enforcing the “no entry- no exit” directive. Nigerian journalists were advised not to cross into Niger, as the relations between border officials of both countries had started to go sour as a result of the sanctions.

Commercial activities at the borders – including Jibiya, the busiest between both countries – have come to a halt with small business owners lamenting the adverse effects on their businesses. Nigeriens at the borders get most of their basic supplies from Nigeria; with zero movement, people in dire need are having to either crawl through the bushes or use a few unmanned crossings.

Cummings predicted that the Niger coup would likely play out in the same manner as other putschists in the West African region and called for diplomacy to avoid a conflict that could spread across the region and benefit armed non-state actors.

“To this effect, the junta will likely provide the international community, particularly ECOWAS, with some concessions. This may be the release of Bazoum – who is likely being held as a bargaining chip – and the provision of a transitional timetable which outlines the country’s return to constitutional rule,” he said.

Gbemisola Animasawun, associate professor at the Centre for Peace and Strategic Studies, at the University of Ilorin in Nigeria, said there is a need for the deadlock to be resolved because Niger was already in a “pitiable situation”.

However, there will be an overlapping effect for both Niger and Nigeria because the borders only exist in the minds of the state actors, he added.

“War is not an option whether directly or by proxy. Stakeholders must engage the coup leader and develop a transition plan,” Animasawun told Al Jazeera.

For Mohammed who is apolitical and has not voted in the last three Nigerien elections, the conflict cannot end soon enough. He is already planning to find a way through one of the smuggling routes into Maradi.

“I am not happy and no one is happy,” he said. “Only God knows the best.”

Freight trucks parked at the Jibiya border between Nigeria and Niger on August 10, 2023, due to the closure of borders between both countries

Africa News of Thursday, 10 August 2023

Source: aljazeera.com

Brothers at ‘war’: Niger citizens bear the brunt of ECOWAS sanctions

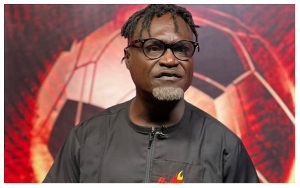

Badamasi Mohammed, a freight truck driver sits beside his truck at the Jibiya border between Nigeria

Badamasi Mohammed, a freight truck driver sits beside his truck at the Jibiya border between Nigeria