Introduction

One of the biggest problems facing the globe today is the spread of false information. Misinformation and disinformation are not recent phenomena. They are as old as communication itself and predate the internet, social media and other sources of information available today.

The urge people feel to distort information in furtherance of their own agendas or interests is the source of this threat. The emergence of the internet and social networking technology and their use to spread misinformation is of great concern to the world. The internet’s ability to manipulate and spread false information has had an unforeseen consequence, despite its value in enabling information to reach a larger audience more quickly. Social networking platforms are another popular medium for spreading and amplifying misinformation.

An analysis by the international media and information advocacy group, the Integrity Institute, showed different misinformation and disinformation amplification factors for the various social media platforms-Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and TikTok.

Jeff Allen, a former integrity officer at Facebook and a founder and the chief research officer at the Integrity Institute, has explained that various social media platforms have different factors for the amplification and spread of misinformation because “the more mechanisms there are for virality on a social media platform, the more we see misinformation getting additional distribution.”

The analysis by the Integrity Institute revealed how some social media sites have algorithms that contribute to the spread of misinformation and disinformation. Many sites also have features for the instant sharing of information which aids the amplification and spread of misinformation and disinformation at a click.

Misinformation and disinformation affect practically every facet of life. From information relating to public health to false reports of the deaths of well-known political figures, misinformation has become a dangerous tool wielded by individuals and groups in their pursuit of goals and objectives. Research has revealed that misinformation and disinformation are more common during national elections.

For a country with high levels of illiteracy, It is impossible to overstate the effect that misinformation and deception have on African countries during elections. Although the aim of spreading false information may not always be to influence the outcome of an election, its main objective may be to obscure the truth, raise doubts among voters and alter longstanding voting habits.

These phenomena have had a significant impact on elections throughout Africa. While a politician losing an election may only suffer minor consequences, the repercussions of a lost election can be disastrous and could include the start of civil unrest, the destruction of public and private property and the need to redo entire election cycles.

Election monitoring and surveillance have become increasingly necessary because national elections are delicate and sensitive democratic exercises in most African countries with the ever-present threat of insecurity, violence and instability. Misinformation is growing in prominence as a potential election hazard, endangering the integrity of the voting processes, compromising democratic procedures and weakening electoral integrity.

Case Studies of Disinformation in Some African Elections

Nigeria

Nigeria served as an excellent illustration of how the disarray of information exacerbated the anxiety surrounding the 2023 presidential election. Before and during the national election, over 83 accusations about the election were verified. Some of these allegations not only sparked problems in neighbourhoods where violence is a problem, but they also discouraged some voters from casting ballots at all. Every facet of the Nigerian election in the reviewed year was tinged with disinformation, ambitious reforms, and security concerns.

The All-Progressive Congress’s (APC) Bola Tinubu won the presidential contest at the end of the voting. As seen by the animated discussions and divergent predictions for the country’s future after the eight-year administration led by Muhammadu Buhari, it was an intense race.

Nothing, perhaps, better captured the intensity of the battle than the degree of misinformation that dominated the information ecology at the time. Even after Tinubu won the final verdict in his favour from the Supreme Court, the trend persisted despite his victory against opposition from several political parties, including Rabiu Kwankwaso of the New Nigeria Peoples Party (NNPP), Peter Obi of the Labour Party, and Atiku Abubakar of the People’s Democratic Party (PDP).

There were also signs that the information disorder around the election worsened the nation’s security and economic challenges.

Côte d’Ivoire

At the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic, Côte d’Ivoire held national elections on October 31, 2020. Before the day of the election, social media was flooded with false information about the epidemic, with viral posts suggesting that the virus and its spread were orchestrated by the government. These posts further suggested that the masks being sold were contaminated with the coronavirus by the Chinese, causing distrust in the protective gear.

There were also rumours that Africans were being used as “guinea pigs” in the testing of the COVID-19 vaccines. Misinformation of this kind has the power to strike panic and terror in citizens and cause mistrust of governments. This was the case in Côte d’Ivoire when Ivorians blamed the authorities for mishandling the health crisis. Due to perceived difficulties with the voting process, this led to a low voter turnout on Election Day.

South Africa

Despite concerns of Russian interference during South Africa’s 2019 general election, the Institute of Development Studies said analysis found that it was a prolific, home-grown disinformation campaign on social media that played a significant role. Between 2017 and 2019, the wealthy Gupta family – with close ties to Jacob Zuma – hired UK PR firm Bell Pottinger to create over 100 fake accounts on Twitter, pushing out at least 185,000 posts – with a notable element of disinformation. One example was the hashtag campaign #Jonasisaliar fabricated by the fake accounts to spread false information to discredit then Deputy Finance Minister Mcebisi Jonas.

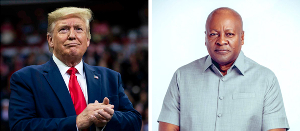

Concerning South Africa’s most recent general election held on 29 May 2024, Wired.com reports that Duduzile Zuma-Sambudla, daughter of former South African president Jacob Zuma, on March 9, 2024, tweeted a video that purported to show former US president Donald Trump encouraging “all South Africans to vote for uMkhonto WeSizwe,” her father’s party, in the country’s May 29 elections.

In another post, just days before the elections, Zuma-Sambudla, who has more than 300,000 followers, shared videos and photos of what appeared to be paper ballots. The accompanying text accused the African National Congress (ANC), the party currently leading the government, of stealing votes.

Sierra Leone

During Sierra Leone’s 2018 elections, there was a rise in tribal rhetoric. The presidential spokesperson, Abdulai Baratay, accused opposition supporters of voting along tribal lines. He later refuted his own accusation, claiming instead that voters were choosing their candidates based on “regionalism,” a term sometimes used as a euphemism for tribalism. As a result of people taking to the streets in protest, there have been more violent occurrences. There was a pervasive sense of fear and tension throughout the entire area due to the growing likelihood of tribal conflicts and violence.

Implications of Misinformation for Elections

False information is spreading rapidly as a result of the fast-paced nature of social media and the anonymity offered by the internet and social media, which is contributing to the global adaptation of new information and communications technology (ICT). These digital tools have been weaponised by governments and individuals, who use them to promote political candidates, discredit civil society organisations and democratic institutions with statements of defamation, incite public unrest and violence through the posting of offensive election-related content, and more.

All of the previously listed methods used by information manipulators to disseminate false information have obstructed electoral procedures and put electoral integrity, credibility and the standard of democratic discourse at risk. Misinformation can impact citizens’ ability to hold elected officials accountable, distort election results, undermine the legitimacy of the democratic process, taint legal proceedings, and compromise citizen data.

The Implications for Ghana

The experiences of neighbouring nations in the region serve as a clear reminder of the difficult task Ghana faces as it prepares for the country’s presidential and parliamentary elections in December.

Navigating the Perils Posed by Information Disorder: A free, fair, and credible electoral process can be ensured by comprehending the ramifications of information disorder and taking note of the lessons these countries have learned. Statistics have demonstrated that one of the main risks associated with election disinformation is the deterioration of public confidence in the electoral process and the work being done by the Electoral Commission of Ghana (EC).

Voters may become sceptical of the validity of the election results as misinformation and disinformation spread doubt and confusion. This was seen in Nigeria where the propagation of false narratives on social media fuelled mistrust in the political process and endangered the election’s legitimacy. After receiving a disproportionate amount of false information prior to the announcement of the election results, even Liberia met the same fate.

Information overload can also amplify already-existing social tensions and differences, which may spark instability and social upheaval. For instance, false information spread during the elections in Nigeria and Sierra Leone sparked off political unrest and tensions, illustrating the divisive power of disinformation on society as a whole.

Information overload can also make it more difficult for citizens to participate actively in democracy and make informed judgments. Misleading stories and material have the power to skew public debate and deter voters from making wise decisions. One such example is Nigeria, where voters’ capacity to evaluate the qualifications of rival politicians and parties was impeded by disinformation that distorted the electoral environment.

Recommendations

Instituting a Fact-Checking Coalition in Ghana

Building on the achievements of other nations’ fact-checking campaigns, Ghana ought to consider forming a Fact-Checking Coalition made up of media outlets, educational institutions, and civil society organisations. This group can act as a centralised point for communicating accurate and trustworthy information, dispelling myths, and confirming election results. The Fact-Checking Coalition can strengthen the efficacy of fact-checking initiatives, boost public confidence in the electoral process and function as a barrier against the dissemination of false information throughout the election season by combining resources and knowledge.

The Nigeria Fact-checkers Coalition (NFC) and the Liberia Fact-checking Network (LFN) worked together to counter false information and advance media literacy in their respective nations. For example, the NFC team painstakingly examined over 127 allegations that surfaced during the election season. These included deceptive political remarks and viral social media posts that were re-disseminated for exposure by over 12 media outlets.

Collaboration Between Government, Media, and Civil Society

To effectively address electoral misinformation, Ghana should encourage increased cooperation between government agencies, media outlets, and civil society organisations. This cooperative strategy may entail the development of multi-stakeholder task forces or working groups tasked with keeping an eye out for and responding to incidents of disinformation. In order to enable coordinated responses to new risks and ensure accountability and transparency in the management of electoral information, regular communication and information-sharing channels should also be established.

Amplifying Media Literacy Programmes

Ghana must prioritise media literacy programs to equip its citizens with the skills and knowledge needed to critically assess media in the run-up to elections. This can be achieved by creating comprehensive educational courses that emphasise critical thinking, digital literacy and methods for verifying information. While South Africa is a leading nation in sub-Saharan Africa in promoting media literacy instruction at various educational levels, countries like France and Britain are also leaders in this regard.

Public awareness campaigns can further support media literacy programmes and encourage individuals to actively engage with diverse information sources while remaining vigilant against the spread of false material. For example, the Nigeria Fact-Checkers Coalition (NFC) made significant investments in media appearances and campaigns to promote media literacy throughout the nation.

Tools, Resources, and Skills for Fighting Misinformation and Disinformation During Elections

Election observer groups should invest in learning the skills necessary to combat misinformation and disinformation, as well as stay updated on digital tools that can aid this effort. Regardless of the type of incorrect information, fundamental abilities are required to effectively combat misinformation and disinformation. Using fact-checking as a weapon against misinformation during elections requires analytical prowess and acute observation.

It is critical to set aside all biases during the process in order to ensure the production and dissemination of accurately verified, impartial information to audiences. Verification requires a variety of instruments and expertise depending on the different forms of fraudulent information.

Conclusion

Misinformation and disinformation destabilise societal cohesion. People create deepfakes and spread fake information on social media, often discrediting others in the pursuit of their own selfish goals and ambitions. Social media handlers sometimes use disinformation to gain more followers, leading to fights and disagreements. To resolve the menace of misinformation and disinformation, the government can use advanced technology to detect, block, and counter disinformation.

The state must also understand how disinformation can impact international trust and security. Misinformation and disinformation seriously jeopardise the credibility of elections and must be fought. Elections everywhere in the world are supposed to be free, fair, transparent and peaceful by international democratic standards.

Africa News of Friday, 5 July 2024

Source: cisanewsletter.com