Gabriella Ghermandi recalls with laughter the annoyance she felt about the so-called Ethiopian Spice Girls - charity-backed pop group Yegna that hoped to change narratives and empower girls and women through music.

The all-female group sparked controversy in the UK because it was partly funded by British aid and some say it was a waste of taxpayers' money. But for Ghermandi, assumptions that Ethiopian women had to be taught by outsiders was the issue.

“I was like, what?” Ghermandi tells the BBC. “They want to teach us how to empower women? Ethiopia? With all its epics of women?”

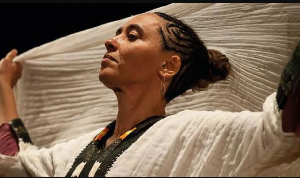

So, Ghermandi - an Ethiopian-Italian author, singer, producer and ethno-musicologist - also turned to music as a way of “saying to the world that we have a huge history about brave women who had as much power as men”.

The result is a nine-track album called Maqeda – the Amharic name for the Queen of Sheba, a hugely important figure in Ethiopian history.

Every song is an homage to female figures, communities, rituals and musical styles.

Many would label this album Ethio-jazz but it encompasses so much more, says Ghermandi.

“It’s a very rooted Ethiopian music, but at the same time, there are very prog sounds, very rocky and punk sounds. You can find everything".

Maqeda was lovingly developed over four years, bringing together the Ethiopian and Italian musicians she has worked with since 2010 as the Atse Tewodros Project – plus Senegalese guest musicians, as well as a beat-boxer and a body music performer.

“We wanted to digest the music,” says Ghermandi of the collaboration, adding that every musician had a role in the arrangements "because I really wanted my two countries to be one”.

Born in Addis Ababa in 1965, to a father from Italy and an Ethiopian-Italian mother, Ghermandi recalls the international feel of the capital city where she spent her early years.

“Every place, every corner was [filled] with music and dance. And I think I learned the rhythm that has stayed in my blood,” she says.

On the same street as her mother’s clothes shop was a record store run by a Greek woman which blasted out an array of sound from Congolese music to the Beatles.

Fela Kuti and other African greats played at the nightclubs where Ghermandi would tag along with her older brothers, while on Sundays there were tea-dancing parties at an Italian expat club.

Although Ghermandi had no formal music training, a thorough immersion in Ethiopian musical styles came from the many wedding and church ceremonies that were part of family life.

Travel was another constant in Ghermandi’s childhood – thanks to her father.

In 1935 he left Italy to work in Eritrea, then an Italian colony. In 1955 he moved to Ethiopia and met her mother, who was 17 years younger.

His jobs in construction took him to remote areas, and Ghermandi would often visit.

She was only three months old when she was taken to the Rift Valley of southern Ethiopia. Her father wanted her to be given a moytse - or “sound name” - by the local Oyda people.

For girls, a cow horn is blown – and whatever sound is heard by a very old and very young woman waiting together underneath a tree in the forest becomes the sound name. Ghermandi’s moytse is tumlele, tumlele, tumlelela.

Her father died in 1978. By then, the military dictatorship of Mengistu Haile Mariam ruled Ethiopia and so, in the early 1980s, by then a teenager, she moved to Italy. Ghermandi now lives between Italy and Ethiopia.

But those cherished early experiences have stayed with her, and this latest album draws on childhood visits to Ethiopia’s remote communities as well as meticulous research as adult.

Ghermandi says she started with the community she grew up with – the Dorze people originally from the southern highlands of Ethiopia, whose women head villages and sing in powerful polyphonic choirs.

You can hear that way of singing – with up to six voices or parts, each with an independent but harmonising melody – in the song Boncho, which means “respect” in the Gamo language.

Ghermandi worked with an Ethiopian female poet to create Set Nat (She is a Female), to counter a common saying in Ethiopia that when a woman achieves something it is because she is as brave as a man.

“I hate this saying, because it used to tell me that it’s not enough to be a woman,” Ghermandi says with passion in her voice. “And I want to say to the world that being a woman is more than enough!”

The song is led by a choir whose call-and-response has a distinct, rhythmic feel in a 7/4 time signature. “This is very typical of a part of Ethiopia – and it is a memory of my childhood,” she explains.

Another track, Kotilidda, honours the matrilineal society of the Kunama people who live close to the borders with Eritrea and Sudan. It showcases the avangala, a two-stringed instrument which sounds like a bass guitar - played only by the Kunama people.

“I really wanted to mix the Ethiopian traditional instruments with modern instruments because Ethiopia does not promote enough its traditional instruments outside the country,” says Ghermandi.

Africa News of Monday, 8 July 2024

Source: bbc.com