The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) is preparing for elections due on December 20, according to the Independent National Electoral Commission. If all goes well, this could become the first election scheduled and conducted on time in a long time, allowing the country to maintain or change leadership by peaceful means only for the second time in history.

It could cost $600 million, some $150 million above budget. Yet that may not be President Felix Tshisekedi’s only headache. His pain is multiple.

Economy

As a member of the East African Community, the DRC has not yet caught on the tradition among peers to read budgets at the same time. The anomaly may be in the accession processes it is currently undergoing. Or there is no such plan.

Congo, the largest country in Sub-Saharan Africa, is endowed with exceptional natural resources, including minerals such as cobalt and copper, hydropower potential, significant arable land, immense biodiversity, and the world’s second-largest rainforest.

Global commodity prices of the raw materials that Congo produces are at an all-time high, which is why its current accounts position has changed from a deficit to a surplus, driven by the demand for electric cars as the world seeks green locomotive energy.

Stronger export earnings in 2022 could, however, not offset higher food and fuel bills, leading to a wider current account deficit estimated at 2.9 percent of GDP from a negative one percent in 2021.

DRC has coltan, copper and cobalt, which are used in making electric vehicle batteries. Now, 70 percent of coltan and cobalt comes from the DRC, as does the highest copper quality in the world, accounting for 30 percent of the world’s supply.

But the benefits from their exploitation are but a blip on the scale. DRC is still one of the poorest countries on the globe.

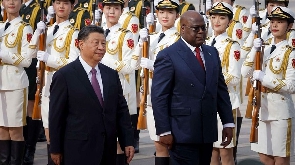

Recently, President Tshisekedi has been vocal about tightening mining agreements, especially with the Chinese. When he travelled to Beijing in May, expectations were that he was going to right the “skewed” contracts.

But he returned home with no deal, forcing his officials, government spokesman Patrick Muyaya, Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Foreign Affairs Christophe Lutundula and Finance Minister Nicolas Kazadi to put up a brave face while explaining why they largely returned empty-handed.

“Many things were done on the sidelines of this visit, in particular the signing of several memoranda between the two countries,” said Muyaya, who is the Information Minister.

The trip from May 24 to 29, he argued, had led to the elevation of ties from a “strategic partnership of win-win cooperation to a comprehensive strategic cooperative partnership.”

“We had to breathe new life into this cooperation,” added Kazadi, “which is extremely important. China today is one of the main economic players on a global scale and the leading investor in the DRC. We, therefore, have a major partner.”

The most important bit – righting weaknesses in the contracts – was never talked about. That could become fodder his rivals during the campaigns.

According to the World Bank, foreign direct investment (FDI) and external financing contributed to build up reserves, reaching 7.9 weeks of imports cover in 2022, from 5.4 weeks a year earlier, and limiting excessive exchange rate fluctuations.

And, though the country’s economic growth picked up to 8.6 percent in 2022, from 6.2 percent in 2021 growth in non-mining sectors (particularly services) was modest, slowing down to three percent in 2022, from 4.5 percent in 2021.

The economy is limping, largely due to pockets of insecurity that persist in the country, particularly in the east.

DRC is currently completing voter registration for the next General Election. But in recent months the security situation in the Kivu and Ituri provinces has deteriorated, with fighting between the army and armed groups forcing thousands to flee. Those may be lost votes.

M23 and Kagame

Rwandan President Paul Kagame may be both a source of Tshisekedi’s headache and tonic.

When he came to power in January 2019, Tshisekedi managed to go against his predecessor Joseph Kabila’s policy and tried to mend relations with neighbouring countries such as Rwanda. He invited President Paul Kagame to the funeral of his father Etienne Tshisekedi in May 2019 in Kinshasa, to the surprise of some people.

Initially, President Kagame warmed up to Tshisekedi as they sought security and trade cooperation. According to Rwanda’s National Institute of Statistics, in 2017, cross-border trade between Rwanda and the DRC generated $100 million, and up to 90,000 people cross the common border every day.

In one meeting, both men vowed to work together to overcome the rebel groups that operate in the jungles of eastern DRC.

In March 2019, Rwanda and the DRC signed a bilateral air service agreement to bolster trade and movement of citizens. This culminated in RwandAir launching its maiden direct flight from Kigali to Kinshasa in April, a route that was expected to ease the movement of goods and travellers.

In May 2019, as relations between Rwanda and Uganda remained frosty, Rwanda turned to the Congo for trade.

But, on May 29, 2022, the DRC suspended its flights, forcing RwandAir to cancel the route schedules to Kinshasa, Lubumbashi and Goma. Today, the Kigali-Kinshasa is operated by Uganda Airlines via Entebbe and or Kenya Airways via Nairobi.

Rwanda and the DRC have not always been friendly. Their armies clashed at the border during Joseph Kabila’s reign. Yet Kabila rarely accused Kigali in public, as Tshisekedi has been doing lately.

Kabila was also considered by Kigali as reluctant to kick out FDLR rebels, who have lived in eastern DRC for close to three decades. Among these rebels are individuals wanted for their role in the 1994 Genocide against the Tutsi.

But the M23, a group Kinshasa has labelled terrorist, is to blame for the current rocky relations and DRC has been accusing Kigali of backing it.

Last month, a UN group of experts gave credence to Kinshasa’s assertions, noting that Kigali has been supporting the rebels through troop reinforcement, equipment and command, and named at least five active top commanders of the Rwanda Defence Forces as coordinators.

But Kigali, while dismissing the UN report as based on “questionable evidence and unreliable sources”, was quick to acknowledge a part of it that “confirms the serious threat represented by the Kinshasa-backed genocidal militia FLDR, and their newly increased capacity to threaten Rwanda’s security.”

Most of the time, suspicion and feeling of need has driven both sides. In February 2021, for instance, a bilateral meeting between Rwanda and the DRC was convened in Kigali to review security matters and forge a way forward in dealing with security threats affecting both countries.

On June 26, 2021, Presidents Kagame and Tshisekedi met in Goma as part of bilateral quest for promotion and protection of investments, avoidance of double taxation and tax evasion and gold mining cooperation to ensure its traceability in DR Congo.

A signed deal then allowed Congolese company, Société aurifère du Kivu et du Maniema (Sakima SA), and a Rwandan firm, Dither Ltd, to mine and refine gold in the DRC “in order to deprive the armed groups of the revenue from this sector.”

But about a year later, Kinshasa suspended all agreements with Rwanda, over the M23 falling-out.

Some Congolese still blame him for his rapprochement with the Rwandan leader while others laud his bravery in publicly denouncing Rwanda, unlike his predecessor. Yet the resurgence of violence breaks one of his promises: Getting permanent peace for the Congolese.

Now, Kinshasa is refusing to negotiate with the M23, despite a push this week by South African President Cyril Ramaphosa, and an inclusive idea fronted by the East African Community that all parties be involved in dialogue this time.

This week, the Facilitator of the Nairobi Process, former Kenya president Uhuru Kenyatta, hinted all groups were back to the table.

And Ramamphosa, on a trip to Kinshasa on Thursday urged Tshisekedi to open talks with the rebels.

“We need to find a framework for negotiation. And President Tshisekedi has never been against negotiation,” he told a joint press briefing.

But President Tshisekedi was adamant: “Everybody knows that Rwanda is backing the M23, despite its denials and the various documented reports by United Nations experts; this country lives off this war of aggression against the DRC to feed its economy. Rwanda’s strategy consists of pushing the DRC to negotiate with M23, while foment dissidence.”

Kabila and allies-turned-foes

There is another problem. With five months to go, political tension is already running high across the country, particularly among supporters of Moïse Katumbi, the presumed contender against the incumbent. Katumbi and Tshisekedi were allies but now shows signs of a bare-knuckled political contest.

Katumbi became an ally of Tshisekedi after falling out with Kabila in 2015. Lately, his close allies have been arrested and detained for offences seen as part of punishment for siding with him.

Mike Mukebay, an MP, is detained for inciting tribal hatred.

Another close associate of Katumbi, Salomon Kalonda Della, has been held since May 30 by the military intelligence, who accuse him of “illegal possession of weapons and plotting a coup d’état”. Authorities also accuse him of colluding with Rwanda and the M23.

The military announced that Katumbi’s adviser had been preparing a putsch to replace Tshisekedi with someone from Katanga, Katumbi’s stronghold, where he was once governor. Other former allies have also become adversaries and they include former president Kabila.

Tshisekedi succeeded Kabila and subsequently weakened the former president’s party, Parti du Peuple pour la Reconstruction et la Démocratie (PPRD), and his coalition, the Front Commun pour le Congo (FCC).

As a former president, Kabila still has influence within and outside the countryand he has reportedly been in talks with some Western and regional entities where he has spoken of a dangerous plot on elections.

Other lost friends, some who were behind his victory in the 2018 presidential election, include Jean Marc Kabund, a former leader of Tshisekedi’s party, Union pour la Démocratie et le Progrès Social (UDPS), who is now in prison.

Military chiefs and senior security advisers have also been removed from the President’s entourage. These include Fortunat Biselele, who was confidant of Tshisekedi, and François Beya, one of his kitchen cabinet members.

Yet, Tshisekedi also netted some former MPs and former ministers of Joseph Kabila.

Under the law, Tshisekedi will be seeking his second and last term of presidency. Propelled to the leadership of the UDPS party in March 2017 to replace his late father Etiene Tshisekedi, Felix quickly assumed the stature of a presidential candidate by first leading a loose opposition coalition, Rassemblement, in 2017.

Yet, unlike his father, he was more inclined to compromise and was less radical. He forged an alliance with Vital Kamerhe on the eve of the 2018 elections.

According to some experts, his election victory against Emmanuel Shadary (the candidate of Kabila) and Martin Fayulu is the result of a skilful mix of day and night alliances. He had been supported by his UDPS party, but also managed to negotiate a secret alliance with Kabila, according to several of the former president’s advisers, who have since made the claims in public.

That surprised the DR Congo and the world, including Western allies in Belgium and France.

Catholic Church

After the 2018 election, Paris and Brussels alleged rigging and the Catholic Church joined in to demand probes. After sometime, the Catholic bishops became the source of heat and coolant on his administration. They criticised Tshisekedi on corruption and insecurity. But they also praised him when he targeted external enemies of the Congo.

With a huge following, the Catholic Church could sway the vote. But the counting of the vote may matter more.

The Church seemed to have sat on its hands last time, only being shocked with the result. Perhaps they will keep an eye on it this time.

History

The son of veteran opposition leader Étienne Tshisekedi, who fought Mobutu after serving as his minister of Interior and Security in the 1960s, Felix Tshisekedi’s political apprenticeship took place in his father’s shadow.

Born on June 13, 1963, Félix only became a major national political figure after his father’s death on February 1, 2017.

Félix grew up as the son of a young minister in the immediate aftermath of Congo’s independence in June 1960. When post-independence events plunged the country into chaos, just a few days after the proclamation of independence, Joseph Mobutu “neutralised” the politicians and installed the College of Commissaires-General, a provisional government that functioned from September 19, 1960 until January 1961. The senior Tshisekedi was part of the government.

The family lived in the opulence of power, but fate changed in 1982, when Étienne challenged Mobutu to the throne.

The all-powerful Mobutu relegated Tshisekedi to his village in Kasaï in central DRC. Felix dropped out of school as the battle became fierce as senior Tshisekedi fought against the one-party system and Mobutu’s dictatorship.

In 1985, Mobutu authorised the Tshisekedis to leave Kasaï and Félix found himself in Brussels. To date, he describes Belgium as his “other Congo.” He studied and worked odd jobs, he has claimed.

He began his life as an activist with the UDPS in Belgium. Félix naturally identified Mobutu as the country’s enemy. Mobutu would be weakened by illness and was ousted from power in May 1997.

The UDPS, meanwhile, continued their fight against the Kabilas, Laurent Kabila and son Joseph.

In 2016, with Tshisekedi Senior’s position weakened by illness, Félix prepared his way to take over. He made important contacts in Western countries. At the UDPS, he became responsible for external relations, with the help of some of the party cadres. Above all, he counted on the support of his mother Marthe Kasalu. She is still seen as one of his closest confidants. He also started to draw closer to Kabila, once an arch-enemy.

Africa News of Saturday, 8 July 2023

Source: theeastafrican.co.ke