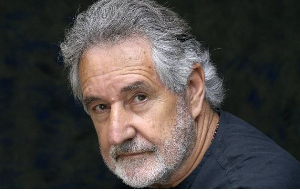

A financial sector specialist with the World Bank, Juan Costain says lack of proper access to banks in most African countries could be a contributory factor to the low level of saving culture among Africans.

Speaking to the dailyEXPRESS via telephone from his Washington office, Mr. Costain said most banks operating in Africa are located only in major cities, making it difficult for people, especially those in the rural areas to have access to them.

“Geographical location is important because people would like to have banks that operate more closely to them because it makes it convenient for them to have access to their money,” he explained.

The dailyEXPRESS called Mr. Costain following a publication in the UK financial magazine, Economist that only 20% of families in Africa save with banks.

The report published under the headline “on the frontier of finance… Taking advantage of more stable economies, banks are venturing deep into sub-Saharan Africa,” said the almost 80% who do not have accounts prefer to save in other family ventures. This is however coming at a time financial analysts on the continent appear to be enjoying what is said to be a good and sustained economic expansion since the post colonial era. For example, the magazine quoted the IMF as saying that “real GDP growth is expected to rise from 5.7% in 2006 to 6.1% this year and 6.8% in 2008.”

This performance, according to the IMF, is partly driven by the rise in commodity and oil prices. Prudent economic management, more openness and more stable politics as well as foreign aid also helped. The resounding policies however mean banks will only not work harder, but will be supported to make them grow.

But Mr. Costain said the saving culture is also poor because people do not have the financial capacity to cater for families let alone save with the banks. According to him, the salaries of most workers are so meagre it will be difficult for people to channel part of their earnings into the banks where they are not even sure of how much interest they’ll make on it.

He also identified the concentration of about 80% of the country’s workforce in the informal sector as part of the reason. Mr. Costain said most economies on the continent are purely cash based and this makes it difficult for the formal sector to attract the needed workforce in its fold. He however identified Ghana as one of the countries that appears to be doing well with more and more people now eager to operate bank accounts. Juan Costain attributed this to the emerging competition in the country’s banking sector, especially with rural banks adding to the swelling numbers of banks operating in the country.

A World Bank report however stated that a positive access to financial services in Africa should be a major priority, because it boosts country’s economic growth while helping to reduce the income gap between rich and poor. But the saving culture amongst most African families still remain the same, with families preferring to put their monies under mattresses or susu collectors.

In a continent where majority of the population operates businesses at the small and medium scale levels, the derived income is re-invested into the business after taking what the family will survive on.

The Economist report mentions that Small and medium-sized firms struggle to borrow; private credit accounts for 18% of GDP in Africa—and less than 5% in Angola, Chad, Congo, Guinea Bissau and Sierra Leone—compared with 30% in South Asia. Ethiopia, Uganda and Tanzania have less than one bank branch per 100,000 people.

“Opening an account in Cameroon requires $700—more than many of its people earn in a year. In Swaziland, a woman needs the consent of her father, husband or brother to open an account or take a loan, and 75% of adults do not have a verifiable address. Even in South Africa, where The report however identified Ghana as one of the shining examples when it comes to the culture of saving. The decision of government to grant licenses to private banks to operate is seen as a healthy seen.

Most of the banks on daily basis continue to increase the growing numbers of customers with innovative measures. Some even operate cashless accounts, something that was unheard of a couple of years ago.

For example, Barclays Bank is working with Susu collectors, who gather money from small-scale market traders and keep it safe for them for a fee. The collectors' clients are typically too small for high-street banks, but Barclays reckons that they collectively represent a market worth £75m ($154m). The bank offers savings accounts, loans and training to the susu collectors, and says they have helped it reach 200,000 market traders. In two years, there have been no defaults.

But the progress to rope in more customer base has been minimal as banks still have to build up necessary scale, cut costs and manage risks better. The continent’s vulnerability other than weather conditions, unstable donor support, and volatile commodity prices, have also contributed to the latest trend.

Countries such as Zimbabwe and Sudan also show that political stability cannot be taken for granted. This residual uncertainty and the lack of confidence in local banks help explain why those who can often prefer to keep their money abroad and why most private finance in Africa is short-term. “Many African countries still have to develop and enforce policies and laws allowing banks to compete and operate more easily, while making sure they are financially solid—and customers are protected.”. The report mentioned a strong regional integration as a panacea for the existing problem.

Business News of Tuesday, 4 December 2007

Source: Mathias AMOAH