When Moscow and Riyadh failed to reach an agreement on 6 March in Vienna, the oil world woke up to a major crisis situation three days later.

Heavy consequences are expected for the producer countries most dependent on black gold, such as Algeria, said Thierry Bros, Associate Energy Project, Davis Center for Russian and Eurasian Studies at Harvard University and Professor at Sciences Po Paris.

The endorsement of Alexander Novak, Russian Energy Minister, was welcomed, not least by the members of the historic Opep, led by Saudi Arabia, who met under the auspices of Opep+. They hoped to develop a strategy to counter the fall in oil prices, since the coronavirus epidemic hit.

Saudi Arabia, the world’s leading crude oil producer, proposed reducing oil extraction by 1.5 million barrels per day worldwide to have a positive impact on prices. This would involve Russia cutting its production by some 500,000 barrels per day.

With no agreement, and in the face of Russia’s firm opposition, Opec member countries, including the seven African countries (Congo, Nigeria, Angola, Algeria, Libya, Gabon and Equatorial Guinea), find themselves engaged in a vertiginous price war from which only the strongest will emerge.

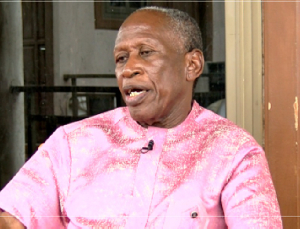

How do you explain the turn of the current Opec+ negotiations around the reduction of oil production volumes?

Thierry Bros: There was a strong chance that this kind of blockage would occur. Historically, beyond Opep+, which is a recent two or three year formation, there has never been any agreement between Russia and the Opec countries.

Because of a strategic error, over the period 2012-2014, when Russia charged high gas prices in Europe after Fukushima, the United States entered into competition. Investment projects developed in American shale gas, cancelling out the benefits of the gas revenue for the Russians in the long term.

This time, Russia did not want to make the same mistake, and preferred to launch an oil price war. Today things have accelerated with the fear of the markets linked to the coronavirus.

Why do oil producers absolutely have to agree?

Like the Saudi and Russian economies, which live mainly off their oil revenues, it is essential to block the production of others (especially the United States). And all the more so in a context of energy transition, where neither civil society nor governments want to hear about fossil fuels any more.

If interests are converging, then why is Russia opposed to the drop in production?

This is all a bit of theatre! As Sadek Boussena, former Algerian Minister of Energy and Mines, and President of Opec from 1990 to 1991, reminds us, when you are one of the biggest owners of oil reserves, as are Saudi Arabia or Russia, it is not in your interest to declare what you are going to do for the next twenty-five years. Let the uncertainty play itself out.

What the producing countries did not know was when they would be faced with this price war, in this case caused by the coronavirus epidemic. However, they already knew the strategy to adopt in the event of a crisis: not to give way to competitors.

What will happen?

In my opinion, there will be no agreement. Prices will continue to fall sharply. But both Russia and Saudi Arabia will hold up well by managing their oil revenues through their stabilization funds.

Asian stock markets plunged into Monday, March 9, after global oil prices plunged into worries that a global economy weakened by a coronavirus outbreak could be flooded with too much crude.

Which countries are the most fragile, especially among African producers?

For many member countries, the consequences will be very difficult. In Africa, Libya will suffer, as will Nigeria, and all the states where oil revenue has to be agreed upon.

For Algeria, things are very complicated because the country does not have a pro-business energy policy. The perennial issue — the hydrocarbons law — still has not been reformed. Add to that the problems of security and corruption, and you end up with conditions that are unfavourable to private investment.

Moreover, oil companies have seen billions of dollars of their value wiped out this morning, losing 10% to 15%. This will therefore limit investment.

In the long run, how far can this crisis go?

I see the price of a barrel below $20 a barrel very quickly. [Brent crude plunged 25% to $33.90 on the Asian market on the 9 March. Today, 16 March, it is under $32/barrel – Ed. note]

The only thing to limit budgetary instability is to see if the States have a sovereign fund. Very few countries in Africa have such a fund.

The first economic consequences will thus be visible in the coming weeks for these oil-producing countries. The social consequences will be felt in the coming quarters.

Click to view details

Business News of Friday, 20 March 2020

Source: theafricareport.com

Coronavirus: Why oil-dependent economies must prepare for the worst

An offshore oil platform is seen at the Bouri Oil Field off the coast of Libya. REUTERS/Darrin Zammi

An offshore oil platform is seen at the Bouri Oil Field off the coast of Libya. REUTERS/Darrin Zammi