Prior to Covid-19, the situation in Ghana looked bright. The central bank was successfully pursuing a single-digit inflation target, the currency was stable and much of the financial system had been reformed and recapitalised. With hindsight, were there any steps prior to Covid that you would do differently, if you had the opportunity?

On hindsight, I would say we took the requisite prudent policy measures to stabilise the economy as well as the financial sector before Covid struck. At the time I came into office in April 2017, the country had inherited an International Monetary Fund programme that was off track. We put it back on track, and successfully completed the programme in April 2019.

The financial sector clean-up was very high on the agenda. The issue of resolving the first, two [insolvent] banks came very early on – I had been in office for barely three months. This was a prior action that was required to proceed to the next stage of an IMF board approval for disbursements to Ghana in August of 2017.

Then, barely a year after that, based on the work of the supervision department of Bank of Ghana, we had to close five more banks that were insolvent. Contextually, these banks had previously received excessive liquidity support from the Bank of Ghana, some of which was misused. By the end of 2018, we had closed down nine banks, 23 savings and loans institutions and 347 microfinance institutions. That was the context.

It was clear these banks were not viable and just giving them liquidity support was not going to change anything. We needed to go ahead and resolve them, put them into receivership and then transfer the positive elements. In the case of the first two banks, we transferred the good assets and liabilities to a larger commercial bank. And then, in the second instance, we had to create a bridge bank, putting all the good assets and liabilities of the five banks in one new bank.

Given the circumstances or the time, we couldn’t have done it differently.

On the macro side, we started off with a robust fiscal stance. From 2017 through to 2019, central bank financing of the budget was zero, even though the Bank of Ghana Act pegged it at 5% of the previous year’s tax revenue. In that context, inflation declined very quickly. Therefore, the monetary policy rate also came down, and growth rebounded strongly. This was the context for the first three years of the current administration.

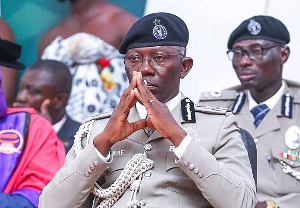

Ernest Addison was appointed governor of Bank of Ghana in April 2017 and secured a four-year second term in 2021. He has spent over 25 years working in public service, with a focus on economic development, monetary policy formulation and implementation, and macroeconomic surveillance.

Addison served as the chair of the board of governors of the IMF and World Bank at the 2020 annual meetings in Washington, DC. He is currently a co-chair of the Financial Stability Board’s regional consultative group for sub-Saharan Africa, chairman of the Ghana International Bank and a member of the Ghana Cocoa Board, among others.

Addison holds a degree in economics from the University of Ghana, a master’s degree in economics and politics from Cambridge University and a PhD with specialisation in monetary economics and economic development from McGill University.

The early stages of the Covid-19 crisis also seemed manageable, growth was robust, but debt built up and restructuring was a challenge. The Bank of Ghana also engaged in monetary financing at a time when many central banks adopted accommodative policies. What were the conversations like at this time between the central bank and the government?

By the end of 2019, the financial sector clean-up was completed. The main banks had been strengthened and the weaker banks were out of the system. The banking sector was poised, with the additional capital through the recapitalisation process, to support financial intermediation. Then, out of the blue, we had Covid-19 pandemic. The government’s response to the pandemic, was captured by the president’s famous quotation that “we know how to bring the economy back, but we don’t know how to bring human lives back”. This was the philosophy behind the government’s approach in dealing with Covid.

Therefore, government spending was ratcheted up to support several intervention schemes that were put into place to mitigate the impact of Covid. Obviously, with revenue shortfalls, the financing of these large-scale expenditures became a challenge.

Prior to that, we had not done any monetary financing, that is financing of the budget had been zero. Therefore, providing financing support to the government was not an easy transition for us to make. We had some good discussions going into it. The finance minister went to Parliament and requested for a suspension of the Fiscal Responsibility Act due to the pandemic. This enabled us to trigger emergency provisions in the Bank of Ghana Act to provide exceptional financing for the government budget. And that’s what we did.

For me, it was a big reawakening, because I did not foresee that the central bank would be drawn into budget financing. But, given global developments especially with central banks in advanced economies, it seemed like monetary accommodation of fiscal policy to meet Covid expenditures had become part of the norm.

In addition, the IMF itself allocated additional SDRs, which are assets held by central banks, and designated these SDRs to help governments meet their Covid expenditures. This meant the central bank could automatically lend on these additional resources to meet the needs of the budget. This changed the psyche – having to on-lend IMF resources plus triggering the emergency provisions to provide central bank financing to the budget. This was difficult for me.

Even in 2021, the government was able to successfully issue nearly $3 billion in debt. That helped to ensure the central bank didn’t have to provide financing.

But it helped to the extent that Ghana weathered the Covid-19 experience much better than most countries in Africa. Our mortality rates were relatively low, and the economy did not suffer as much as it did in other places. We had a positive growth rate, when others recorded recessions.

So, the fiscal impulse worked in keeping the economy stable and saving lives. But, by the end of 2020, we had recorded a very large fiscal deficit, debt had jumped to 80% of GDP and debt-servicing had become a major constraint for the budget. Nonetheless, the central bank returned to zero financing and did not provide additional financing in 2021.

That wasn’t an easy task because the red flags had started emerging. We had to work very hard to ensure that from 2017 to 2021, there was only one occasion in which the central bank provided financing.

Before moving on to 2022, was there anything you or the government could have done differently – perhaps seeking fiscal support earlier from the IMF, although this may not have been simple given the other debtors?

It wasn’t a simple task. We were already active in the capital markets and had issued several sovereign bonds. Investors were interested in the Ghana story and were following economic developments closely. Even in 2021, the government was able to successfully issue nearly $3 billion in debt. That helped to ensure the central bank didn’t have to provide financing.

But then we had reached a point where the additional borrowing was just helping to facilitate debt-servicing payments. So, I’m not sure if there’s anything we could have done differently, because the markets were still open to Ghana despite the fiscal stance after Covid.

Then, in early 2022, Ghana lost access to the capital markets, inflation shot up to 54% and the cedi lost around half of its value within a year. Can you describe what happened and the actions Bank of Ghana took to try to address them?

At the end of 2021, inflation was at 12.7%. We had started tightening monetary policy rates in 2021, far ahead of the US Fed – and at a time when a lot of other central banks were still in accommodative mode and not tightening policy. We raised the policy rate by 100 basis points in November of 2021. But in February 2022, we had a rude shock when Moody’s followed by Fitch and S&P downgraded Ghana’s creditworthiness.

That immediately led to a loss of market access, and it became clear to everybody who knew the Ghanaian economic indicators that this was going to be a difficult period. As a result, the central bank had to provide some accommodation. But, even then, we managed it quite well. For the first three months of the year, the access levels were not significant.

By the second quarter, however, things began to change. The currency took a severe hit because of significant portfolio outflows and heightened speculation about an IMF programme. Because of the strong stance of not going to the IMF, we began to lose reserves and government spending was far in excess of its revenues, including debt-service payments – we had to continue to service debt even though we had lost access to the market.

This is why the central bank lost close to $3 billion reserves in 2022. The foreign exchange market became disorderly, and the cedi depreciated sharply. Once you get that type of exchange rate depreciation in a country like Ghana, the pass-through to price level changes is rapid and becomes quite significant.

By the middle of the year, it became obvious to the government that the only way out of the crisis was to approach the IMF.

When the IMF came in, the issue was how to solve the problem in an orderly manner. So, we had to continue to service the debt, continue to refinance the budget, so that salaries could be paid, and government payments continue, knowing very well that there was a solution down the line with an IMF programme. By then, Parliament had not restored the Fiscal Responsibility Act.

Together, with the IMF mission that came, we agreed that, given the situation as it was, the central bank had to provide the financing until we could reach an IMF staff-level agreement by the end of the year – and hopefully get IMF board approval, so the IMF programme could kick in. We all agreed that it was a sub-optimal policy outcome but the most efficient way to handle the crisis to prevent a disorderly collapse.

This meant Bank of Ghana had to stand in as a lender of last resort until the IMF programme was in place. It also meant the country continued to service its debt to both domestic investors and foreign investors throughout this period. The only way we could meet those foreign currency payments was to use the reserves buffers we had accumulated over the years.

So, the IMF was supportive of that?

Yes, the IMF was supportive, as there wasn’t any other way. But as we approached the end of the year, and the discussions with the IMF had progressed significantly. It became clear that the only way Ghana could proceed with the programme was to conduct debt restructuring. This restructuring by the government was announced in November 2022. This negative news hit the value of our currency and created quite a bit of tension and disorderliness, which only stopped when we reached a staff level agreement with the IMF at the end of the year. Thus, the staff level agreement restored some degree of certainty about the economic outlook for Ghana.

But the disorderliness we saw in the Ghanaian economy between November and December could have started at the beginning of 2022, had it not been for the Bank of Ghana’s financing support. Bank of Ghana postponed the disorderliness by using central bank financing. And we would never have known what the consequences of a disorderly adjustment would have had on the Ghanaian society and politics?

What are the key components related to the IMF programme? And what elements involve reaching agreement with Chinese creditors?

IMF programmes are meant to be the country’s own programmes that the IMF then supports. I am referring to Ghana’s post-Covid programme for economic recovery. The key ingredients are standard measures to increase revenues to the budget and ensuring there is cost recovery in the utility sectors – for example, related to electricity, water – looking at state-owned enterprises for efficiency gains, and reducing fiscal risks to the budget. So, it’s quite heavily focused on fiscal measures.

A key policy on the monetary side is meeting our inflation target. This includes a monetary policy consultation to ensure the monetary policy rate keeps focused on bringing down inflation. Another element is to have a floor for the accumulation of reserves. And then there is zero financing of the budget.

For the financial sector, we have had issues about the restoration of capital to some of the banks because one of the impacts of the domestic debt restructuring had been huge losses for banks and therefore banks have to rebuild their capital.

Did that involve haircuts?

Nobody took a haircut on the domestic front, except the central bank, that served as the loss absorber by taking a 50% haircut on all non-marketable holdings of government instruments, to meet the debt thresholds for the approval of the IMF programme by the board.

Would you please explain that?

Most of the savings came from the restructuring of domestic bonds into ones with longer maturities that required lower immediate interest payments. Most of the investors, especially the pension funds, strongly resisted the significant losses. It is fine to have technical advisers who will look at spreadsheets and calculate the savings you need to generate and tell you how to get these amounts of savings from a certain group; it is quite another matter implementing these measures in real life.

The political economy was such that after three to five months of negotiations a lot of the stakeholders managed to get away without any significant haircut, instead lengthening the maturities of their debts in return for lower interest payments. Therefore, the central bank had to take an effective 50% haircut to enable Ghana to meet the debt threshold required for the IMF programme approval.

Presumably, you weren’t very happy about that decision?

We were not. We did raise the matter with the IMF. The IMF brought in central bank balance sheet experts to look at our accounts who, by the time they were done, were of the view that despite the haircut, we were policy solvent and we could still operate.

The issue of reviewing the central bank’s accounts would have to be revisited in another three years. Obviously, this was a time we needed to make progress to ensure the Fund’s board meeting took place. The central bank had become almost the last obstacle to getting Ghana’s programme approved at the IMF. Therefore, it was difficult to spend too much time on further discussions.

So, the central bank was hit harder because the other parties negotiated so strongly?

The other parties – pensions funds – probably do not accept they did not take a hit because they are all complaining. But I think they got off relatively easier than they would have if the initial permutations had been followed. We had to take an additional haircut because of that – from 35% to 50%.

Has the Bank of Ghana determined whether it would need to be recapitalised? If so, have talks begun with the Ghanaian government or will that be delayed for three years?

It is the recommendation of the IMF technical assistance mission to review the situation in three years. But we will be asking for early recapitalisation.

When will you ask for it?

We will see. I have said on many occasions that, even if you had the most perfect law, what happened in 2022 would have been no different. Because you had a major economic crisis on your hands, we would have had no other option than to recourse to central bank financing to survive.

Have you had any signal that early recapitalisation would be something the government would be amenable to?

It’s a complicated matter because it’s a vicious cycle. Under the terms of the debt restructuring, any additional bonds issued by the government will defeat the objective of dragging down the debt-to-GDP ratio. The fund is struggling to recommend when would be the most appropriate time to issue debt to recapitalise the central bank.

The Bank of Ghana has ended monetary financing of the state. Do you think the laws/rules surrounding monetary financing require reform?

Definitely, I have said on many occasions that, even if you had the most perfect law, what happened in 2022 would have been no different. Because you had a major economic crisis on your hands, we would have had no other option than to recourse to central bank financing to survive. If you look at the history again, we have operated with this law successfully for five out of six years. To say the law is weak is not really the issue.

Will there be a legal change happening any time soon?

We have advised that the timing of reviewing the BoG Act must be appropriate. The thing about laws is that when they go into parliament, they might not come out as expected. You need to be concerned about what finally comes out. This is really the issue.

Will Ghana be able to manage tight fiscal consolidation, especially with an election year coming up?

Ghana doesn’t have a choice but to do so, because we have all seen what an economic crisis can do. The lessons are fresh on everybody’s mind. And the need to keep the currency stable is paramount going into the election.

Given your experiences, do you believe central bank independence is possible in Ghana moving forwards?

Central bank independence is relative. We have acted independently for most of the time that I have been in office. I have not had to consult anybody to set interest rates. Bank of Ghana is relatively independent. We have an inflation targeting framework. We have a Monetary Policy Committee that sets interest rates. Independence is all about operational independence. Once you have the structures and the tools to do that, you are there.

Inflation has fallen to around 35%. When do you think it will be possible to get it down to your target of 8% ± two percentage points?

We are looking at a three-year horizon under the fund programme to get it back to single digits. The October inflation was 35.2% and the advantage we have is that we had very large price jump in November 2022, so the base-period effects will come into play in November 2023. We expect to see a very significant fall in inflation by the end of the year.

That would mean, if you looked at a graph, we’ll be returning to our trend. You saw the spike in 2022 and then we will trend back to 12–14%, which is where inflation was hovering for the last few years before the crisis. So, I don’t think the inflation record is as bad as it sounds.

Do you see the Israel-Hamas war as an upside risk to inflation forecasts? What about conflicts in other parts of West Africa or high US dollar interest rates?

The implications from the Israel-Hamas war during the past few weeks for our region are linked to oil prices, which so far have remained relatively low at around $80 per barrel. It is an area we need to keep an eye on because of the implications that transportation, food and other costs have for inflation. So far, we have not seen the turmoil in West Africa as a major risk. But security spending in the budget could come under enormous pressure and complicate the fiscal management process. The European Union has donated some military equipment, so we have received some help. On the federal funds rates, the main risk is of higher rates prompting further outflows from emerging markets, which always puts a lot more pressure on local currency and then on imported inflation.

Ghana’s gross international reserves (excluding encumbered assets and petroleum funds) were equal to one month’s imports at the end of August. Where are they now, and when might Ghana hit the three-month threshold?

I believe in October, the reserve equivalent was 1.1 months of import cover, better than they were in August. But the three months’ reserve target is again part of the three-year horizon. What I can say is that our domestic gold-purchasing programme has put us in a better situation than before. This year alone, we have been ahead of our reserve target by almost a $1 billion. So, we plan to continue with the domestic gold for reserves programme. And that should help in terms of building reserves going into 2024.

How did the gold programme develop?

We had never focused on the gold part of reserves, always holding the same 8.7 tonnes or so for the last 40 to 50 years. We realised we were producing a lot of gold. There is a lot of activity out there. So, the question then came up as to why not buy more gold to increase our reserves. It was one of those moments when an obvious policy that could have been implemented several years ago appears to make a lot of sense, especially during the post-Covid period when we were looking at several ways to manage the crisis. We started it in 2021.

Has it had a material impact on helping to stabilise the currency, or is it mainly due to the IMF programme?

Yes, it has a material impact in helping to stabilise the currency, especially this year. That’s because the gold reserves programme has raised over $1 billion, compared with the IMF’s $600 million disbursement since the start of 2023 – with another $600 million due in November/December. So, it is a significant amount.

What is the status of Ghana’s CBDC pilot, which I believe includes an offline operational capacity?

The central bank did a lot of things due to the favourable conditions at the end of 2019. The economy had stabilised, inflation was low, so we started thinking about enhancing the digital economy. The government was keen to digitise everything, so we thought it was a good time to research the feasibility of an e-cedi central bank digital currency. We cooperated with technology providers and established a fintech office at the central bank, staffed with very sharp young innovators.

Within six months, they developed a concept and conducted a pilot in some of the remotest parts of the country, due to this offline feature of the digital currency. It appeared to have worked very well, both in offline and online modes. The Ghanaian population is used to mobile money, so the concept of a digital currency was easily absorbed – it’s not an alien concept to people.

The e-cedi came in the form of tokens on mobile phone applications. Participants were given up to a certain value to spend within their locality. They were very enthusiastic, to the extent that some of them exhausted their budget and had to use their own resources to buy more tokens. Because this was central bank money, there was a lot more trust in dealing with a digital form of the e-cedi, helping to improve the perceptions of those that participated in the pilot. The results were very positive.

After the pilot concluded, we started serious discussions on the commercial side but then we had Covid and the economic crisis, which reordered our priorities between 2020 and 2022. We thought that was not the time to digitise a currency which had lost 50% of its value. So, we have slowed down on it, but hope to return to it when the situation improves.

But, as I speak, there is an e-Cedi Hackathon taking place and there is a sandbox. I understand the enthusiasm from the fintech community is so great that the original shortlist had to be tripled. There are some very interesting ideas coming up in the hackathon.

When do you think you may be able to revisit what to do with the CBDC project – will it also be at the end of the three-year period?

Probably it will be earlier than that. As I mentioned, we have reached the point of trying to understand the commercials a little bit more.

Business News of Thursday, 14 December 2023

Source: centralbanking.com