Ahead of the mid-year budget review proposals scheduled to be presented to Parliament tomorrow by Finance Minister Ken Ofori Atta, concerns of stakeholders, the local private sector and the international financial community inclusive have shifted from the contents of the review with regards to policy proposals, to how the inevitably enlarged fiscal deficit can successfully be financed.

Apart from the fact that government is officially targeting a fiscal deficit of nearly seven percent of Gross Domestic Product, well above the self-imposed cap of five percent imposed by the fiscal responsibility law passed in 2019, the International Monetary Fund has pointed out that the actual deficit will be far higher, at around 9.5 percent of GDP.

This means that while government is stating that it will need gross deficit financing of about GH¢16.1 billion for 2020, (based on projections made earlier in the year), the IMF reckons that deficit financing needs could go as high as GH¢22.2 billion, of which only GH¢18.1 billion has been locked in.

Government and the IMF have disagreed on the size of the public debt, and the size of the fiscal deficits that have contributed to the debt levels over the past couple of years, because government has insisted that two major debt components – energy sector debts and financial sector bailout costs – be treated as exceptional costs which are effectively “off balance sheet items”.

However the IMF disagrees, and has come up with parallel figures as contained in its review of Ghana’s fiscal situation in response to its request for a Rapid Credit Facility (which it subsequently granted to the tune of US$1billion).

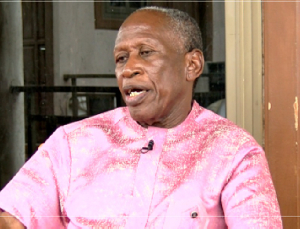

Critics of government’s position in its disagreement with the IMF’s position – led by immediate past finance minister, Seth Terkper – point out that no matter how government chooses to classify those debts, they still have to be financed and by taking them off the public balance sheet, the government is pretending to ignore a cost it is nevertheless having to meet.

So far government has creatively used exceptional sources of deficit financing to relieve pressure on the domestic financial markets that would otherwise have resulted in a sharp increase in local interest rates.

These include GH¢10 billion in direct emergency funding from the Bank of Ghana, GH¢500 million from the sale of non-marketable securities, US$1 billion from the IMF itself, and major further financing from the World Bank.

Ghana is also enjoying savings of some US$500 million this year from the suspension of debt servicing payments on debt from bilateral creditors, although acceptance of this offer arranged by the G-20 closes the door to any further Eurobond issuance this year.

This strategy has been largely successful so far, with treasury bill rates remaining more or less stable through the second quarter of 2020.

However the sheer size of the deficit to be announced tomorrow – coupled with the fact that the real financing need will be considerably higher – could easily push interest rates significantly upwards.

Seth Terkper himself points out that the government needs to raise somewhere between 60.22 percent and 65.84 percent of its financing needs from a “relatively weak domestic market.” Importantly this does not include financing roll overs of maturing debt if the holders of the maturing debt securities decide to exit.

In April, government came to an agreement with the Ghana Association of Bankers that commercial banks lower their lending rates by 200 basis points on current and new loans while COVID-19’s impacts persist. This came on the back of 150 basis points cut in the BoG’s key Monetary Policy Rate from 16 percent to 14.50 percent.

The worry now is that an excessive domestic financing needs going forward will force interest rates upwards anyway.

Click to view details

Business News of Wednesday, 22 July 2020

Source: goldstreetbusiness.com