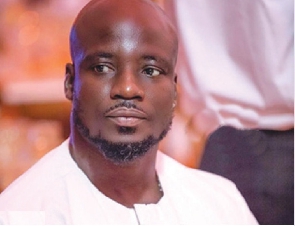

Benjamin Aidoo has brought his dancing pallbearers to more than 200 funerals in Ghana, easing loved ones to their final resting places to the strains of everything from reggae to gospel music. “Customers say, ‘Papa loved dancing when he was alive, let him dance one more time,’?” says 27-year-old Aidoo, who charges as much as 800 cedis ($387) a ceremony.

“This is a new business where we dance the coffin to the grave instead of marching solemnly,” he says. Aidoo founded his business in 2010 and is now having to turn customers away.

Funerals, among Ghana’s most important social gatherings, have become a large and growing industry that stretches far beyond traditional services offered by mortuaries. Today, entrepreneurs are in high demand to supply everything from local drummers to the intricately—and often whimsically—carved coffins that are a staple of Ghanaian send-offs. And since costs for the elaborate affairs can easily exceed the annual earnings of an average resident, the country’s biggest insurers, including Enterprise Life Assurance and SIC Insurance, have seen funeral coverage become a major source of business.

Fueling the fast-growing spending on funerals is an oil-production boom that boosted Ghana’s yearly economic growth rate to 15.9 percent in 2011, from 3.1 percent in 2007, and increased gross national income per capita almost fivefold, to $1,550 in the last decade.

Stretching over days, funeral ceremonies, called celebrations in Ghana, involve church services, receptions, and burials. Families spend thousands of cedis on food and drink, shaded seating, a disc jockey or band, traditional drummers, brochures, posters, photographers, and often a videographer to capture mourners filing by the casket.

“Our funerals have become a big drain on families,” says Vicky Wireko, who writes the Reality Zone column for the Daily Graphic, Ghana’s biggest-selling newspaper. Its classified pages are filled every day with full-color obituaries that list “chief mourners” and far-flung relatives. “No wonder families are turning to the banks to seek funds,” Wireko says.

While relatives have traditionally contributed to meet funeral costs, those donations are no longer enough. “When the burden to finance funerals became so high that people began taking out bank loans, we saw there was space for insurance,” says C.C. Bruce, executive director of Enterprise Life, a unit of Enterprise Group.

Enterprise Life’s funeral insurance policy is now the company’s “flagship product,” accounting for more than 65 percent of revenue, Bruce says. Lump sums of as much as 5,000 cedis are paid out. Enterprise’s shares, which more than tripled this year, posted the second-best performance on the Ghana Stock Exchange Composite Index, which has gained 65 percent. “Funeral costs are high,” says Anastacia Arko, an analyst at Accra-based Databank Financial Services. “People are becoming sensitized to take up?…?policies.”

Stanbic Bank, the Ghanaian unit of South Africa’s Standard Bank Group (SGBLY), introduced funeral insurance plans last year, offering a lump sum of 1,000 cedis at monthly premiums of as little as 2.50 cedis. (Ghana’s minimum daily wage is 5.24 cedis, or about $2.45.)

But the country’s biggest insurer, SIC Insurance, plans to increase the maximum payout of its funeral policy as customers complain of rising expenses, says Alfred Ankrah, SIC’s funeral policy manager. “We have a policy targeting the so-called upper class that pays out 10,000 cedis, but still people say it’s not enough,” Ankrah says. “There is a call from society to prevent expensive funerals, but it’s not working because people want to make sure that the person they lost sleeps in peace.”

Funerals have always been extravagant, with coffin carvers on the streets of the capital Accra charging up to 2,500 cedis for caskets in shapes ranging from a catfish to a soccer shoe, but many locals say they’re now being stretched beyond their means. “Ghanaians spend too much on funerals,” says David Dogbe, a 30-year-old business-development specialist at a telecom company who had to borrow 2,000 cedis from a friend to meet his 5,000-cedi share of a 20,000-cedi funeral for his father-in-law in March. “It’s because of the social pressure.

People will come and look at the funeral and say, ‘Oh, he didn’t want to pay for this or that,’?” says Dogbe, who spent two weeks traveling between Accra and the eastern town of Ho to organize the event.

Death and money are inextricably linked in Ghana because funerals are meant to both celebrate the life of the deceased and show the success of a family, and flamboyant funerals carry more social prestige than any other ceremony, says Marleen de Witte, an anthropologist at the University of Amsterdam who’s studied Ghana’s funeral economy.

“Most Ghanaians agree that they are spending too much money on funerals, but as soon as somebody in their own family dies, the social pressure to hold an impressive funeral proves very hard to resist,” she says. To curb costs, tribal chiefs have issued funeral guidelines ranging from prohibiting all-night wakes to restricting the number of drummers. But their pleas haven’t been heeded, De Witte says.

Deliberations on the date and location of a ceremony and the subsequent preparations mean that bodies spend an average of two months in a mortuary, says Jacob Konlan, a clerk at the Korle-Bu Hospital mortuary, the country’s biggest morgue, as dressers in scrubs apply makeup and cotton wool to corpses on cement slabs. Outside, groups drum and wail while relatives wait to retrieve the bodies.

With the arrival of refrigerated morgues, even the body’s length of stay has become an indicator of a family’s wealth, he says. The cost of storing a body is 400 cedis a month. “People boast about how much they spend on a funeral,” says Aidoo, the dancing pallbearer. “They say with pride: ‘I spent 10,000 cedis.’ Ghanaians spare no expense because we care more about the dead than the living. Just die and you will see how many loved ones you have.”

Business News of Saturday, 24 August 2013

Source: Bloomberg