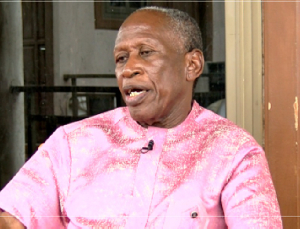

Government’s monetary policy interventions aimed at easing the negative effects of coronavirus on the economy seems risky and might become a liquidity trap because of weak investor sentiment and a slowdown in economic activity, Dr. Jerry Kombat Monfant – a global strategist and economic consultant, has warned.

The Bank of Ghana (BoG), in response to economic disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, announced a reduction in policy rate by 150 basis points to 14 percent, and a drop in regulatory reserve requirements from 10 percent to 8 percent to increase supply of credit to the private sector – with commercial banks being persuaded to provide a syndicated credit facility of GH¢3billion to support key industries.

They are also to grant a six-month moratorium on principal repayments for selected businesses.

While Dr. Monfant, who is also the President of MBIC Group – a global management and strategy consulting firm, sees this as an important step by the Bank of Ghana, he warned that in the current situation it could easily become a liquidity trap as the economy is faced with low growth: “Encouraging banks with the bait of policy rate reduction and setting up a liquidity trap is dangerous.

“Banks should not fall into a trap by using runnable deposits of customers to grant up to the tune of GH¢3billion and offer a moratorium of six months while deposits are declining. This policy intervention could paralyse Ghana’s banking sector, and the non-performing loans will surge,” he said.

Conventionally, he said, banks are limited by profitability considerations which determine their willingness to grant loans and not monetary policy decisions. They also base lending decisions upon perceptions on the risk of return/trade-offs, and not reserve requirements.

Buttressing his point, he said in the prevailing business climate investment will be very unresponsive, including the banks, since demand for investment at this crucial moment is not dependent on interest rates reduction.

The question any economic pundit will ask is: “What is the demand for goods and services while domestic and global economies are slowing down?”

Businesses will have to be very cautious because business confidence is very low. Therefore, despite the low interest rates, firms don’t want to invest. If the financial institutions grant such facilities, there is more likelihood of financial diversion because they have low expectations of future profits,” he said.

To him, the only way commercial banks can increase their lending capacity is to secure new deposits. “The truth, however, is that the reserve requirements do not act as binding constraints on banks’ ability to lend and consequently create money. The reality is that banks first extend loans and then look for the required reserves later. So, if the central bank intends to reduce the banks’ reserve requirement from 10 percent to 8 percent as a tool of easing lending, that could just be an ‘impotent’ position.”

Whereas the central bank holds the view that fractional reserves in these circumstances are effective, Dr. Monfant believes this is not fool-proof as it can also fail. Explaining further, he said during a bank-run, panic will allow depositors of all classes to demand all their money at once – which would exceed the amount of reserves at hand and lead to potential bank failure.

“Government should be aware that monetary policy is not the only tool for managing aggregate demand for goods and services. Fiscal policy, taxing and spending are others; government taxes have fallen, and this has reflected on business growth and the purchasing power of citizens.

“While foreign countries are using Quantitative Easing (QE) as a tool to influence spending through the capital markets, doing the same using the banking system could be dangerous,” he concluded.

Click to view details

Business News of Wednesday, 3 June 2020

Source: thebftonline.com