Until mid-December last year, Strategic Mobilisation Ghana Limited (SML) was like any ordinary business in the country – judiciously deploying its skills and talents in the concerted effort of nation building.

Except for a few publications, mostly on its numerous corporate social responsibility (CSR) activities, the indigenous business quietly worked with state agencies to account for and guard the state’s interest in refined petroleum products as part of a wider government policy to ensure every tax revenue in the downstream petroleum sector is duly identified and collected for national development.

Then on December 18, 2023, a news report around aspects of its operations made SML a national topic – triggering whirlwind discussions that have been more emotive, presumptive and political than factual, exhaustive and research-based.

While the audit directed by President, Nana Akufo-Addo continues, it is important to properly examine the issue in a way that forces the discussion back onto a path of facts instead of assumptions.

This is even more important because as various ‘experts’ fall over each to throw mud at the company, SML and its management have been measured by what they say – partly in deep regard for the due processes that have been rolled out by government.

The danger with that measured silence, though, is a deepening of the information gap and rise of disinformation on an issue as technical as revenue assurance in the downstream petroleum sector.

Experience, not hearsay

Over the past 10 years, my professional journey has led me into the intricate realm of Ghana’s petroleum downstream sector – offering first-hand experience in a dynamic industry that plays a pivotal role in the nation’s economic landscape.

To help with discussions on the issue, I share my encounters, observations and insights during my days as auditor and currently as operational manager for one of the biggest bulk oil distribution companies in Ghana.

The sector is run in parallel by the National Petroleum Authority (NPA) and Ghana Revenue Authority (GRA). The NPA regulates and supervises ordering products between the OMCs and BDCs by basically being in charge of compliance. GRA, on the other hand, plays the role of tax regulator by ensuring taxes are billed and collected based on traded data volume received.

BDCs’ Products Imported and Deferred Taxes

Ghana’s petroleum downstream sector is a multifaceted ecosystem, and at its core lies the BDCs – which are responsible for importing, storing and distributing petroleum products.

This exploration delves into the products imported by BDCs and the intricacies of deferred taxes, shedding light on the financial and regulatory dimensions of this crucial industry.

The deferred tax system allows BDCs to import products and defer the payment of Customs duties and taxes until the point of sale, which shifts the tax and other duties responsibility to the Oil Marketing Companies (OMCs) – thus providing financial flexibility for the BDCs.

While deferred taxes offer financial flexibility, effective cash flow management becomes paramount for BDCs to meet their obligations when due; GRA on the other hand loses tax and duties receivable through this chain of complexities.

Depots and Custom Bonding Operations

Ghana’s imported finished petroleum products have their first interactions with the depots, a vital component of its energy infrastructure involving a complex interplay of processes.

Depots serve as logistical hubs where bulk quantities of petroleum products are stored before distribution. These facilities play a pivotal role in ensuring a steady and reliable supply chain.

Custom bonding operations add another layer of complexity to the downstream sector. These operations involve the storage of imported petroleum products under a Customs bond before they are released into the domestic market.

NPA Traded Volumes and GRA Taxable Volumes

The interaction between volumes managed by the National Petroleum Authority (NPA) and those subjected to taxation by the Ghana Revenue Authority (GRA) stands as a critical element. My exploration into this dynamic revealed the delicate balance required to ensure both efficient energy management and fiscal responsibility.

The NPA has put up a system required by BDCs and OMCs to trade finished petroleum products by initialising orders to successfully release actual products from the respective depots. These volumes must be wholly transferred to GRA, so as to ensure execution of the Special Petroleum Tax Act for revenue mobilisation.

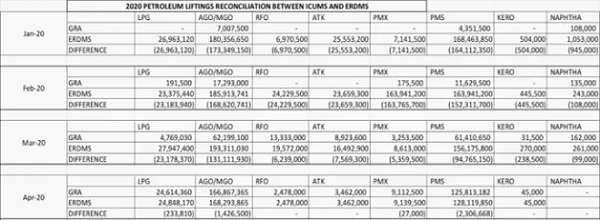

Over the years, GRA has suffered suppression of traded volumes for tax purposes – as shown in Figure 1 below.

For more elaborate evidence that challenges the GRA in its quest to fully bill and collect downstream petroleum taxes, Figure 1 depicts the gap between the NPA traded volumes and GRA taxable volumes for the period January 2020 to April 2020. The element ‘DIFFERENCE’ shows the unaccounted-for volumes due the GRA.

Figure 1 – Traded (NPA) and Taxable (GRA) Volumes – Jan to Apr 2020.

SML Bridging the Gap

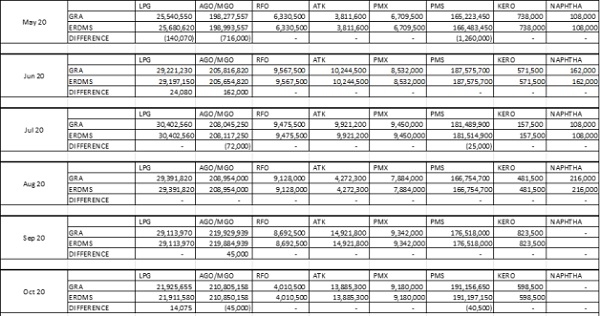

My investigation has shown that SML’s revenue audit and assurance control measures. implemented during May 2020 in the petroleum downstream sector, closed the gap between NPA traded volumes and GRA taxable volumes. The analysis here as shown in Figures 1 and 2 clearly show that the assurance implemented by SML played a pivotal role in the performance of taxable volumes and, by extension, revenue performance.

Figures 1 and 2 also show clearly the gap-bridging of NPA traded volumes and GRA taxable volumes for the previous loss to gains after the assurance and audit.

Figure 4 – Traded (NPA) and Taxable (GRA) Volumes – May to Oct 2020

With the above disclosures, which are verifiable with the NPA and GRA, let well-meaning Ghanaians seek better clarity as to who wants SML out of the audit and assurance services they render to GRA.

While at it, there are key questions that must also be asked:

1. How many BDCs own OMCs?

2. Does the NPA have its own meters or do they rely on depot meters?

3. Before SML, which meters was the GRA relying on at depots?

4. Before SML, how was the GRA keeping waybills?

Why, with the NPA-ERDMS system in place, was the GRA experiencing under-declarations and concurrent OMC monthly indebtedness that led to court cases which remain unresolved?

Before SML, why did the sector experience at least one OMC running away with collected tax revenue?

Genuine answers to these critical questions will lead to the realisation that SML plays a crucial role in revenue assurance and collection of taxes due the state.

Click to view details

Business Features of Tuesday, 30 January 2024

Source: Matthew Alorvi, Contributor