At least a million mourners turned up for the funeral of Nigerian musician, and voice of the downtrodden, Fela Kuti, his manager Rikki Stein remembers.

“The road was filled with people as far as the eye could see,” he says looking back to that August day in Lagos in 1997.

The King of Afrobeat, who was revered by the people but feared by those in charge, had died at 58, reportedly of complications from Aids.

But Stein believes that Fela, who had been repeatedly arrested for speaking out against successive military regimes, actually passed away because of a much deeper cause.

“Fela died of one beating too many. His body was covered in scars and his mind and spirit had to cope with 200 arrests. The system can only take so much,” Stein tells the BBC in an interview to mark the publication of his memoir – in part about his 15 years managing arguably Nigeria’s most influential musician.

Throughout his long career Fela defiantly criticized those in charge, notably a succession of military rulers, lampooning them in albums such as Coffin for Head of State.

His music had the power to grab people from the inside and help them start to imagine another world.

“I was gob-smacked,” Stein, now 81, says as he talks about first coming across Fela’s albums in the 1970s.

“The music spoke to me in a way I’d never encountered, exuding warmth, intimacy, excitement, and a constant feeling of anticipation. Every word spoke directly to my inner being, vividly describing life under a totalitarian regime, but I saw clearly how the message could be applied to any country.”

It is perhaps unsurprising that managing someone with such charisma and vision was unpredictable and hectic.

Their first encounter in a hotel room in London in 1982, when Stein was hoping to persuade Fela take part in a music festival, hinted at what was to come.

“As I entered a wave of intense heat hit me.

“It was winter and extremely cold. I was wearing a hat, a coat, a scarf and a sweater. Fela, I learned, always carried additional heaters when on tour to approximate a temperature that he was used to.

“Fela was sitting on a couch, dressed in just a pair of Speedos [swimming trunks]. We shook hands and he invited me to join him on the couch.

“I commented on the heat and began removing some layers of clothing, although I didn’t get down to my Speedos. Suddenly we both laughed, beginning a friendship that endured for the rest of his life.”

Later that year Stein travelled to Lagos to discuss becoming Fela’s co-manager. Very early on, he had a sense of how much influence he had in his home country.

Stein was stuck in passport control while those in charge, behind some smoked glass, were idly checking the documents.

“Suddenly there was a commotion in the baggage hall. It was Fela Kuti, climbing over the carousels and heading towards us, shouting ‘Rikki!’. When he reached me, he gave me a hug.

“’What are you doing, standing there?’

I indicated the smoked-glass window. He walked over and clicked his fingers above the glass. The passport appeared. ‘C’mon Rikki, let’s go’.

“Fela drove us off. He was a great driver but, man, he drove fast, much as he lived his life.”

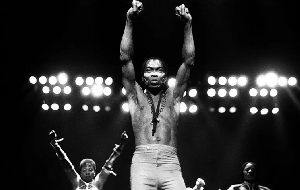

Over subsequent years, despite the intensity, Stein never tired of experiencing Fela performing on stage at full throttle.

“Fela reigned supreme.

“He was everywhere at once; playing keyboards, soprano or alto sax, the occasional drum solo, a sinuous dance from one side of the stage to the other and then it was time to sing, the ever-present spliff held in his elegant fingers.

“For sheer mastery, panache, style and guts, nobody could or can beat this guy.”

His performances were not mere concerts they were events – none perhaps weirder than an infamous show in Belsize Park, north London, that involved a simulated death and a surprise resurrection.

In 1984 Fela was appearing on stage with his mystical guru, a Ghanaian man known as Professor Hindu.

On the morning of the London show, Stein got a call from the publicist who was at the venue.

“’The Professor is here, digging a grave just outside.’ I called Fela, asking him if he knew why. ‘He doesn’t ask me why I play saxophone and I don’t ask him why he digs graves.’

“That night the Professor appeared on stage in a short skirt, a bib and the lampshade. His assistant, Emmanuel, joined him and sat down on a chair.

“The prof began sharpening a huge meat cleaver on a stone, then grabbed Emmanuel and began hacking away at his throat. Blood flew in every direction.

The club was in pandemonium. A limp Emmanuel was carried outside and placed in the grave.

“Come Sunday a large crowd gathered around the grave. Suddenly, the earth began to move and a hand appeared! I pulled Emmanuel out. His hands were warm.”

That year was also when the authorities in Nigeria had obviously had too much of the musician’s outspokenness.

Fela and the band returned to Lagos for a break before embarking on a US tour. Stein had given him a large amount of cash to cover food and hotel bills.

On his arrival in the country, the security officials made out that Fela had failed to declare the money, which was required at the time.

He was detained and then appeared before a military tribunal which sentenced him to five years in prison.

Stein believes this was never about the money. The military saw him as a thorn in their side and wanted to silence him.

But it had the opposite effect. His arrest caused a worldwide furore, Amnesty International declared him a prisoner of conscience and his music became more widely known with radio stations devoting whole days to his work.

A new album – Army Arrangement - had been recorded before Fela went to prison and Stein was hoping to release it.

Short of cash, he accepted a deal that the tracks would be remixed with reggae drum and bass to make it more commercially appealing.

“Someone smuggled a copy to Fela who, mortified, said that hearing it was worse than being in jail,” Stein says. The remix was never released.

Looking back at their time together, Stein feels that it was wild and unpredictable, and yet Fela inspired him with his energy, bravery and philosophical outlook.

“People used to say to me: ‘Wow, it can’t be easy managing Fela.’ I’d explain that I never had any difficulty with him because we were friends. You can say anything to a real friend, so we never had a problem.”

But in 1997 Fela became gravely ill.

When Stein learned of his friend’s passing, he immediately boarded a plane to Lagos to join the mourners.

“On 11 August 1997 Fela was to be laid in state in Tafawa Balewa Square.

“The family arrived at the morgue to collect his body. I’d brought my electric razor and attempted to shave him and comb his hair. A big spliff was put in his right hand and he was placed in a glass coffin and carried in a hearse.

“He was laid to rest in front of his house, Kalakuta, in Ikeja on 12 August.

“His son, Femi, played a plaintive sax solo. A gentle rain fell like perfume. During those days no crime took place in Lagos.”

Entertainment of Wednesday, 26 June 2024

Source: bbc.com