As the discourse on copyright infringement in the Ghanaian music industry reaches its peak, an Intellectual Property Rights lawyer has illuminated the issue of artistes' music being used without proper authorization in political campaigns.

It could be recalled that back in 2020, Ghanaian artiste Worlasi Langani lodged a complaint against the National Democratic Congress (NDC) for using his song 'One Life' in a documentary without his permission.

Although promises were made by the party that the issue would be resolved, in a 2022 interview, Worlasi revealed that he had never been compensated.

Fast-forward to 2024, another musician, DJ Azonto, requested substantial compensation of $10 million from Dr Mahamudu Bawumia, the flagbearer of the New Patriotic Party (NPP), for the unauthorized use of his hit song 'Fa No Fom' during campaign events.

Although his complaints had yet to be addressed at the time of publishing this article, questions have arisen about the use of songs, royalties, and authorization in the music industry.

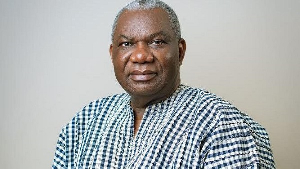

Intellectual Property Rights lawyer, Emmanuel Kantam Duut Esq, in a conversation with GhanaWeb’s Isaac Dadzie, explained the intricacies of the matter regarding songs being used during campaigns, as well as who should be held responsible for such infringements.

According to Duut, the law remains largely silent on the specifics, leaving much to interpretation and expertise in the field.

The crux of the issue revolves around whether a politician can be held liable for the unauthorized use of a song during their campaign.

Thus, if a claim is to be made, the question should first be asked: whose decision was it to use the song? The producers of the campaign video? The DJ at the rally? Or the politician himself?

"You have to be very sure, or you have to be able to prove whether or not the use of your song during the political campaign was under the instruction of the politicians, or the DJ personally used it on the campaign rounds.

"You cannot hold the politician directly liable for dancing to your tune if he/she didn't call for it, especially if it is a campaign rally or a campaign programme where a DJ has played the song," he said.

Thus, to be certain of who to sue, the artiste in question has to determine the party responsible for the decision.

In the case of DJ Azonto, if Dr Bawumia denies having any involvement in the decision for the song to be used at his rallies, the case could be dismissed.

But if the right parties are discovered, what next?

If it is determined that the DJ at the event or the producers of the documentary were the ones behind the unauthorized use, the responsibility, as Duut points out, falls on the party responsible for paying what is known as 'public performance rights'.

These royalties are collected by performance rights organizations (PROs) on behalf of the artistes.

In Ghana, the Ghana Music Rights Organization (GHAMRO) is the main PRO tasked with this role.

"Once your music is subject to registration in the catalogue of songs being registered under GHAMRO, clearly GHAMRO is responsible for the collection of your royalties, not necessarily the person that is using that song or the DJ.

"So you have to follow up with GHAMRO to institute actions for whether or not there has been compensation made to the artiste for the public performance of that song or for the airplay of that song in that regard," he added.

For artistes seeking compensation for the public performance or airplay of their music during political campaigns, the path forward is clear. And it's not through press releases and warnings on social media.

They must engage with GHAMRO to initiate actions and ensure that due compensation is made for the use of their creative works.

ID/BB

Watch the latest episode of E=Forum here

Entertainment of Monday, 24 June 2024

Source: www.ghanaweb.com

Can artistes sue politicians for unauthorized use of their songs?

0 seconds of 52 minutes, 15 secondsVolume 90%

Press shift question mark to access a list of keyboard shortcuts

Keyboard Shortcuts

Shortcuts Open/Close/ or ?

Play/PauseSPACE

Increase Volume↑

Decrease Volume↓

Seek Forward→

Seek Backward←

Captions On/Offc

Fullscreen/Exit Fullscreenf

Mute/Unmutem

Decrease Caption Size-

Increase Caption Size+ or =

Seek %0-9