Emma Hardelin and her group, Triakel, revive Swedish Christmas songs - “It is not all depressing. I promise.”

My grandmother likes to ask me: “What is a nice Jewish boy like you doing running around the world looking for Christmas music? Don’t you get enough of it at the mall?” In fact, it was songs such as Barbra Streisand’s over-caffeinated version of Jingle Bellsthat compelled me to pack my bags and begin a quest to see if the rest of the world substituted their rich folk traditions for cheesy pop songs.

The answer came in Venezuela, where I found Jesus.

Not that Jesus. Jesus Rondon is the fiftysomething founder of a group called Vasallos del Sol (Servants of the Sun), whose music is dedicated to the folk traditions associated with Venezuela’s two solstice festivals (St John the Baptist in June, and Christmas).

The Venezuelan Christmas certainly isn’t white, but its streets are decked out with the familiar Nativity scenes, Santas and ornamented trees. “I think we’ve been watching too much television,” Rondon says.

The Christmas songs, though, are different. Venezuela’s most popular style of Christmas music, parranda, has origins in the Christmas aguinaldo singing tradition, where villagers paraded from door to door singing and asking for gifts and drinks. Many parrandas have branched out into secular themes. The most notable example of this is President Chavez’s favourite band, Un Solo Pueblo, whose hit, Viva Venezuela, is a virtual anthem. Musically, the parrandais a fusion of African, Spanish and indigenous roots.

Christmas music is alive in the carol-filled streets, especially in the villages, where tiny chapels are packed and filled with music that borders on the ecstatic. Along the Caribbean coast, these structures often are little more than shacks with a few photos of Christ. There is no organ, but lots of drums.

That trip marked the beginning of my decade-long, global quest to find out what happened to Christmas folk music. The next stop was West Africa. On the flight, I was seated next to a white American businessman called Bert, who explained how he was going to convert the “voodoo-loving Africans” to Christianity. I tried to smile as he played me a film on his laptop of a group of Africans learning Jingle Bells, but kept quiet about my quest to learn how Africans combine “voodoo music” with Christian spirituals.

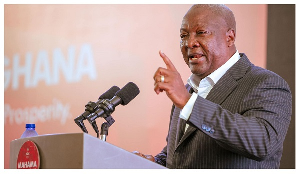

The most popular style of music in Ghana is “highlife”. It incorporates Western genres, fusing jazz, swing, military brass music, Trinidadian calypso, Cuban son and older West African rhythms. Ghana’s Christmas celebrations are a mix of East and West, with stilt walkers and masqueraders dancing to large highlife carolling ensembles.

The Ghanaian Theo Boakye (who now lives in Toronto) created a pan-African Christmas anthem with his group, the African Guitar Summit. Their infectious Afe Hyia Pa darts between four languages – Swahili, Malagasy, Kinyarwanda and Ghanaian Fanti – and, like the Christmas music I heard on other continents, it unifies folk and religious traditions.

By contrast, in Scandinavia the streets are quiet during the long winter nights. They weren’t always silent. Emma Härdelin, who leads the revival trio Triakel, says, “In the 19th century, it was a custom for musicians to just show up on strangers’ doorsteps in December, saying, ‘We’d like something to eat.’ ” Sweden once had a carolling tradition in which musicians would parade through villages, but that custom died out several generations ago. Härdelin didn’t want the music to disappear as well. “Most of Sweden’s traditional songs are forgotten, and now everyone sings Silent Night and other American standards,” she says. Härdelin and her group began digging through archives to find material to produce a recording entitled Wintersongs.

One of the most captivating is the sombre recording of Torspar-julaftas-vaggvisa. To a nonSwedish speaker, the arrangement with fiddle and harmonium paired with Härdelin’s touching vocals gives the impression of an old spiritual. In fact, the song is a recent composition about a poor family: the father runs off and leaves his seven children together in one bed in a cold house with a holiday feast that consists of one mouldy biscuit. “Not all of Sweden’s Christmas music is this dark,” Härdelin says. “Actually, our holiday music is cheerful. This song is more like the rest of our music – most of which I’d call pretty depressing.” Triakel is now getting ready for a series of evening performances of acoustic Swedish Christmas songs in small churches and at the Stallet Folk Centre in Stockholm.

A subdued Swedish church seems a world away from the raucous Venezuelan chapel-shack. However, both houses of worship are filled with people searching for a spiritual, rather than a commercial, Christmas. I found similar scenes in the Louisiana Bayou, Caribbean street parties, Hungarian dance halls and the Canadian Arctic.

My album Think Global: World Christmas is the result of my journey. While I doubt that these songs will end up in shopping centres, it shows another kind of Christmas music. My grandmother even likes it. She’s now complaining how irritating Chanukkah music is. “Maybe that can be your next project?” she says. My suitcase is already packed.