Nostalgia is a child of memory – and memory: is a priceless function of experience. Only one who has seen a lot will have tales aplenty to share.

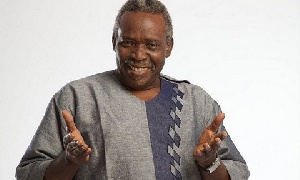

In the time Olu Jacobs has been involved in the world of make-believe, many wars have come and gone, several legends have been made and a handful of nations have risen and failed.

It’s been over fifty years and the giant of African cinema is still standing, still working and quite active.

Nostalgia express

Having schooled in Lagos state model college, Badore (situated at the tail end of Ajah), going to interview Olu Jacobs in Langbassa, a neighbouring community, already had a deep nostalgic connotation for me.

The school shaped me and the area exposed me to a lot of what I know today.

Arriving his home of many years and delving into a conversation where he took me down his memory lane was fitting – having been earlier immersed in my own reverie.

We were in mutual nostalgic mode.

Jacobs, having lived over seven decades, has witnessed changing fads, the extinction of old technology and emergence of new creations.

Despite his powerful presence and an aura of authority, Jacobs is now demure with age, gentled by the years.

Softly, with varying pitches, he talked about the fascinating things of old.

“One has been so involved that you don’t think of how bizarre things are. There was a time we used to carry big boxes around as telephones and you would not be able to make or receive calls in some areas.

“Television came to Nigeria in 1955 during the Western government headed by Obafemi Awolowo. It was fantastic that we could see them and hear them talk immediately.

“I was in Abeokuta and by 5am, we used to race all the way to Ake because there was a public viewing centre there – so you had to rush to get a position,” he recounted with the excitement of a child.

Jacobs says he was pulled into the arts by watching the likes of Julie Coker and Ted Mukoro perform live.

Their performances, which he described as captivating, struck a chord in him and ignited his fire of filmmaking.

With a smile plastered across his freckled face, he paused as if to catch a fleeing memory.

Then he smiled again, this time, from ear to ear — like one who just received a good piece of information.

And he blurted out: “They were magical. They dragged me into it until I settled and accepted that this is my life.”

The faithful epiphany

Jacobs had always been an innate art aficionado but he never felt a connection until a certain day when he was “sent on an errand” by his mother.

“I saw a lorry, people sitting, playing music and the music was good. They were giving out leaflets, I got one and showed it to my mom at home.”

But like the typical Nigerian mother, she was concerned about his chores.

“She said: ‘Ehn, go where? Have you done all I asked you to do? Do it and let’s see what happens’.”

A condition had been placed on his attendance and he was determined to surmount it.

“I went to my brother and we quickly finished all my chores, my mother couldn’t believe it then she said she would allow me.”

“On the day we got there, there was a long queue, luckily for us, I was at the foot of the stage. All of a sudden, the lights went off, Hebert Ogunde’s music started and the lights came back on.

At that point, Jacobs had his epiphany and realised that he was among kindred souls.

“I sat there and I told myself that this is what I will do. There is nothing better than making people feel good. From there, I featured in all church productions even the ones that were supposed to feature only girls.”

Father's death and the journey to England

Actualising his dream of becoming an actor was a bittersweet process.

Jacobs had wanted to travel to England to pursue his ambition but his father opposed him – for mainly two reasons: because he was the closest to him and would surely miss his companionship, and secondly, he said he may die before his son returns to Nigeria.

The latter happened — and it shattered the actor who was perceived as his father’s right-hand man and listening ear.

“My dad used to enjoy his Star beer and I was the only one who had the courage to ask for some. I am the fourth child but I was his favourite,” he said, with nostalgic fondness.

His first acting gig in England came by happenstance.

Jacobs had tagged along with a friend — a fellow wannabe actor — to audition for a movie. While there, he was urged to audition and he impressed.

As fate would have it, he got the role.

“I went to England in 1964. Then, every black actor I knew were based in London and there were too many actors chasing too few jobs and outside London, there were no blacks. Then to get a role, you had to be a union member, to be a union member, you had to have a job. You would go to castings and they would say ‘sorry, your name is not on my list’.

“One of my friends who had gone to England before me was a member. He was going one day and I asked if I could go with him. We got there and I read to the director. He said go and meet the production manager. By the time a bigger agent took over, I was one of the top actors my former agent recommended.

“Then I told my agent that I wanted to start taking jobs outside London because there were no jobs in London,” Jacobs recounted.

Return yo Nigeria

After two decades of working as an actor in England, thoughts of home clung to his heart and he made the decision to return, if not for anything, but to help develop the Nigerian movie industry.

“I looked at everything after 20 years and then I saw where I was and all the things I had been doing and if I could do half of them in Nigeria, I would have been able to help a lot more people,” he said.

Returning to a structureless movie industry wasn’t exactly the most inviting of decisions, but he took it and journeyed back to Nigeria.

Upon arrival, reality danced in his face like a mosquito hovers around a sleeping prey – but he was sure that coming back was the right decision.

“When we started, we were sure we were going to make it,” he said.

A year after he came back, he met a lady who would eventually become his wife, best friend and life partner.

Jacobs said that when he laid eyes on Joke Silva, he immediately knew she was the one.

“I met after a year that I got back. When these things happen, they just happen. I was invited, we were having a production and I saw a beautiful lady, I just consulted our director.

“When it happens, it happens. She’s my best friend, it’s her natural position,” he quipped.

Together, they have charted the path and blazed the trail for today’s generation of filmmakers and actors.

From inception, they were both certain that the sweat of early days will build a structure, an industry that would birth a generation of actors and thespians, Jacobs said.

“When I retire, the one thing that will make me feel fulfilled is when I can watch the new generation and say yes, we did it,” he declared, partly triumphant, partly expectant.

Entertainment of Tuesday, 4 April 2017

Source: thecable.ng