Here are some possible words to grade Ghana’s recently announced 5G policy: Fumble, Falter, Flounder, Flop, and Fail. They all share one letter: F. 5 Fs, to be precise. And a clear stop short of “G”. More to the point, they represent a series of mistakes of escalating significance and danger.

The Minister responsible for the policy has in recent comments accused critics of perpetual pessimism and naysaying. I think the Minister is not being fair to her critics. At least, on this website, we have been very clear and sincere in stating our challenge with her approach. Let’s also hasten to add that we have very specific suggestions for the government about how the situation may be improved.

Far from being cynics, we are interested in a constructive debate for the purpose of improving the policy and enhancing the welfare of telecom consumers in Ghana. We simply want the right thing done for Ghana.

New 5G Policy Rationale is hard to grasp

The entire policy is premised on bringing in a consortium to build the 5G network so that what happened to the earlier generations of telecom infrastructure in Ghana (from 1G to 4G) would not happen again. In the Minister’s thinking, previous government policies, strategies, and regulatory decisions led to a monopoly, namely MTN, that led to the undercutting of rivals, and suppressed competition. The secondary effects of that outcome were lower innovation, higher prices, and poor service.

Each of these points are contentious. According to the government’s own views of ITU rankings and assessments that the Minister herself constantly touts to buttress claims of superior national performance, Ghana’s digital performance is higher than that of many other African countries. It would be hard for that to be true if the country’s telecom landscape was that bad.

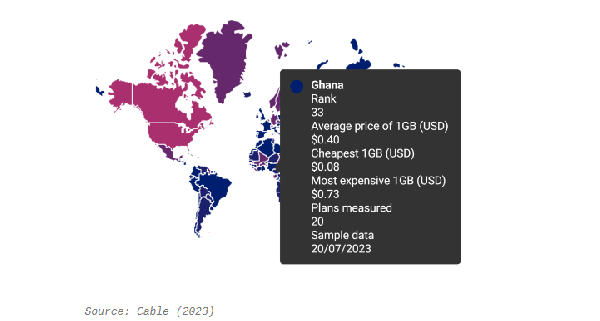

For example, in a recent report by well-known comparisons research outfit, Cable, Ghana ranked third behind Nigeria and Malawi in Africa for the cheapest mobile internet (data) prices. Globally, it ranked 33rd, beating countries like Rwanda, Kenya, the United Kingdom (UK), Singapore, Hong Kong, Estonia, South Africa, and the Netherlands.

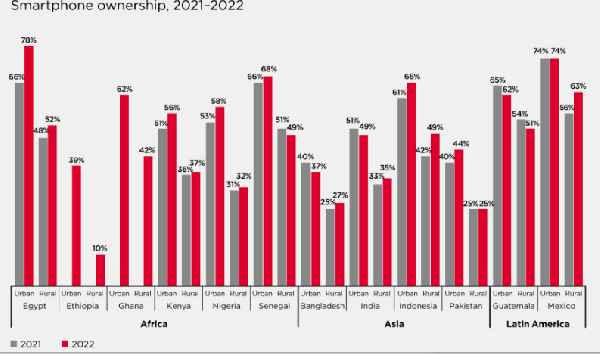

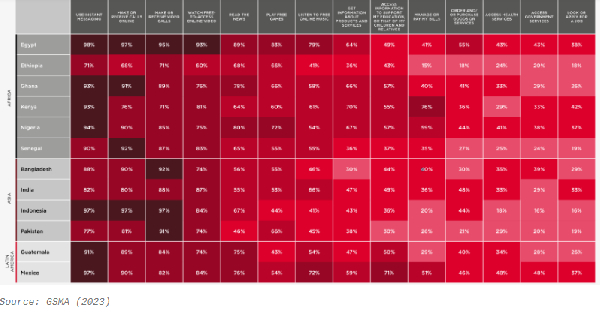

Regarding coverage, the GSMA ranked Ghana third In 2019 for mobile connectivity. In 2023, the country scored commendably in various dimensions surveyed by the GSMA, such as in rural smartphone penetration and digital engagement.

When some of us express caution about viewing some of these nice-looking, international, portrayals of Ghana with nuance, it has been the duty of government spindoctors and affiliates to dismiss us as killjoys. Why the about-turn now? Anyway, let us look homewards.

According to the NCA’s own monitoring results (see example here), the pass-rate for the telecom operators in Ghana for quality of service is usually in the 99% range.

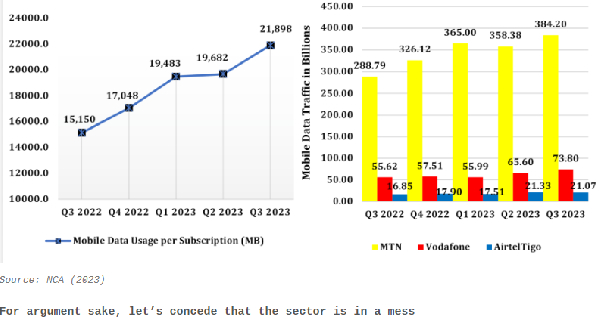

Mobile data/internet traffic and subscriber (per capita) usage have been increasing steadily, implying broad consumption growth.

Still, let us, for the purpose of this analysis, accept this opportunistic position of the Ministry of Communications & Digitalisation that the telecom situation in Ghana is terribly bad due to longstanding policy and regulatory mistakes, which have led to an abusive monopoly.

We readily accept that most consumers of telecom services in Ghana would definitely like to see a major improvement in price, quality, and coverage. While the lead regulator, the National Communications Authority (NCA), does not conduct consumer satisfaction surveys with any regularity, there is substantial anecdotal evidence of consumers demanding far better service and prices than what is currently on offer.

Furthermore, there is also evidence of decreasing mobile internet penetration, even as the market share of the market leader, MTN, inches towards the 80% mark.

The pullout of Tigo and Airtel from Ghana, and the effective collapse of Globacom and Kasapa, as well as the devastating failure of the specialised broadband companies like Broadband Home, Busy Internet, Surfline, and Blu Telecom (with only Telesol hanging on for dear life), all clearly also underline serious structural issues at an industry level even if some international reports and indices say that consumers in Ghana are better off than those in some other African markets.

Let us not delve into any of the various causes mentioned by close observers of the industry as being responsible for some of these structural challenges. Talk about cost of doing business, macroeconomic turbulence, regulatory inflexibility, over-licensing, etc. should all be skipped for now.

Let us also not fret about the fact that in the fixed voice and broadband internet subsegment of the industry, where MTN has no historical advantage, and where Vodafone/Telecel dominates, decline and stagnation has been much more worrying. Fixed voice subscriptions have collapsed to a figure below 1% of the population whilst fixed data subscriptions are stuck below 0.4% of the population.

Nor do we need to draw any insights from the fact that Vodafone/Telecel’s considerably more total monopoly status in the fixed internet and voice space has not paved the way to massive profiteering or growth, even though 99% of that submarket still remains uncovered. Rather, Vodafone/Telecel has struggled to find the resources to deepen investment to leverage its overwhelming advantage.

For now, let us assume that the only, or at least only significant, problem in the telecom sector is MTN’s monopoly position, which, in light of its SMP (Significant Market Power) designation, we can assume it has been abusing.

We will also for the sake of simplicity accept that even though the Ministry’ claim of 4G penetration being stuck at 15% is false since the NCA’s own data show that, as far back as January 2023, penetration stood at nearly 30% (meaning it is presently around 40% judging by recent mobile internet shift trends), monopoly is the cause of this relatively low penetration rate.

We won’t look at the coverage map analysis that suggests that the relatively lower penetration rate is most likely due to handset capabilities (i.e. the physical mobile phones many subscribers have are not always 4G-enabled) rather than to network capabilities. In fact, we will take a cue from the Communications Ministry and dismiss MTN’s claims that more than 99% of its cell sites are aleeady 4G-capable as baseless lies. Just another scheme of deception by the great and evil monopoly.

All these concessions notwithstanding, we are still left with the question: is the government’s new 5G policy the right way to fix the structure of the industry, break the real and perceived MTN monopoly, enhance competition, and thus improve on pricing, quality, and coverage? The answer from where we sit, is unfortunately, no.

Here are five key reasons why critics like the author of this essay oppose the 5G policy in its current form.

1. There is no “consortium” worth its name in place (fumble)

We must start from scrutinising the Communications Ministry’s solution: the consortium. According to her, a “world-class” consortium has been formed that will ensure a level playing field for all market participants so that MTN does not dominate the 5G market.

How exactly the consortium will prevent MTN from leveraging its existing subscriber base to dominate in 5G is not explained. Since, presumably, this new consortium will sell 5G connectivity to all telcos, it is completely unclear why MTN wouldn’t simply buy connectivity for its current ~80% share of the mobile internet subscriber base and continue to hold on to them. After all, its price leadership as far as data costs are concerned has already been curtailed by anti-SMP policies and yet it continues to lead.

But let’s assume that somehow, crazy as that sounds, the Consortium will sell poorer-quality services at a higher price to MTN and sell best-quality alternative offerings at a lower price to other operators to help them outperform MTN. Or even that MTN will refuse to buy 5G connectivity from the consortium and so will be stuck on its current 4G network. While, of course, its competitors surge forward towards the 5G Nirvana.

The question that then arises is whether the consortium has the capacity to build a parallel (standalone) network or take over the network of one of the other operators (telco or tower lessor), deliver infrastructure upgrades to ensure 5G capabilities, and assure excellent connectivity to telecom operators for the ultimate benefit of Ghanaians. That depends precisely on the companies backing the Consortium and the people running the Special Purpose Vehicle setup to operationalise it, Next Gen Infraco.

Our research establishes clearly that the global companies – Radisys, Nokia, Microsoft, and Tech Mahindra – mentioned by the Minister as constituting the Consortium are not legally members. Next Gen Infraco’s incorporation documents and submissions to the regulator, the NCA, establish clearly that there is a local clique in charge, and no global companies.

The Directors of Next Gen Infraco are as follows:

According to Next Gen Infraco’s incorporation documents, Amina Maina of MRS Holdings, a Lagos-based corporation, and Tenu Awoonor, formerly of the pre-merger Tigo, are the initial Directors of the entity.

Whilst the well-known K-Net owns 5% and the two Directors own ~0.35%, the overwhelming shareholders of the entity are Ascend Digital and Integrated legal Consultants, with ~94% of all shares.

More saliently for this discussion, there is a single beneficial owner:

Ms. Olusola Ogundimu is the Chief Executive of Integrated Legal Consultants, and the Corporate Secretary for Ascend Digital. In law, therefore, the entity as currently structured is ultimately controlled and set up for the benefit of a partner of a law firm that is widely known to be nominee and trust-holder for a wide array of companies. So much so that the tax status of Ms. Olusola Ogundimu became a matter of serious contention at the Ghana Revenue Authority between 2014 and 2017.

Our contention is that Ms. Olusola Ogundimu is not some kind of super-investor whose standing can be said to be synonymous with the equity interests of Radisys, Nokia, Tech Mahindra, and the like.

Furthermore, in our previous essay on this topic, we went to great lengths to show that Ascend Digital is a mushroom entity with no serious heft in the industry.

Whilst K-Net is well-established, its recent entanglement in another “imposed monopoly” saga involving the same Ministry of Communications’, in the case of the management of the Digital Terrestrial Television (DTT) migration process in Ghana, raises concerns of it having joined the same clique complained of above. At any rate, it only holds 5% in Next Gen Infraco.

Extract from lawsuit writ by Ghanaian television operators against the government for imposing K-NET as a monopoly service provider to handle, and charge for, all connections to the national DTT platform

2. This “consortium” has no committed financing or serious financial backing and will struggle to raise funds (falter)

When the government gave the “consortium” – Next Gen Infraco – a bill of $125 million for this grand strategy, it said it could not raise that kind of money. The government then decided to spread the fee over nearly ten years for it to pay in tranches.

Next Gen Infraco’s license application dossier for the 5G license, which we have painstakingly examined, showed that the entity lacks the full complement of a management team, committed financing, and skilled large-scale infrastructure capacity. Our due diligence uncovered serious issues in the backgrounds of the few key personnel the entity has been able to attract to date.

All of these findings lead us to a very worrying conclusion: Next Gen Infraco will struggle to raise adequate financing to build a parallel 5G network or to commercially take over and upgrade an existing network.

And, mind you, 5G rollout isn’t cheap. Most of the cost drivers anticipated by McKinsey six years ago have not significantly abated: high power costs, greater need for fiber to connect cell-sites (with all the right-of-way issues that requirement implies), newer and more expensive antennae, a higher density of “filler” micro-cells in-between the main macro-sites, and higher capacity links to the backhaul, among others.

Whilst 5G equipment vendors continue to double-down on the hype, and some industry evangelists lap it up (cooing about 5.5G despite weak global 5G penetration), more independent observers have noted disappointing (sometimes barely 5% of predicted throughput) – even declining -performance, and concluded that in markets with economic circumstances similar to Ghana, such as Bangladesh, financial viability is far from assured in the near future.

With such uncertain bankability, it is rather incredibly naive to expect that a consortium formed by financial upstarts will be able to deploy nationwide 5G in Ghana within 6 months.

3. The exclusive license awarded to Next Gen Infraco is a major impediment to investment in the telco industry (flounder)

The Ghanaian telecom landscape already features infrastructure companies that are not telecom operators. Two, in fact. One of them, ATC was already mulling a 5G infrastructure buildout before deciding to hold on.

There is a range of other broadband connectivity companies that have been contemplating deploying wholesale 5G solutions, including enterprise-level “mobile private networks” like Huawei has been offering to large customers like Bui Power (using a 4G eLTE solution, true, but upgradeable to 5G).

By deciding to award a 10-year exclusive license to Next Gen Infraco, the government has thrown a major spanner into the spokes of investment planning across the industry, and scared off potential new entrants and financiers.

4. The government has thus created a “hustler monopoly” that can only become an “extortion racket” (flop)

The clique represented by Ascend Digital and Integrated Legal Consultants is also the directing force behind the national Common Platform, the World Bank – funded e-Transform national infrastructure, the Smart Workplace system, and AT, the state-owned telecom operator.

Clearly, someone has been steadily, grindingly, and relentlessly assembling a behemoth to dominate the telecom sector, but using raw and brute state power. The award of the 5G license to this clique is founded on a belief that these disparate pieces can then be integrated as the backbone of a dominant operator that will force the current tower companies to capitulate, and ultimately leave MTN and Telecel no choice than to rent 5G towers from the new entrant.

The risk to this “clever-diabolic” strategy is that financing for these kinds of escapades in Africa at the level required is hard to obtain because those who can put up such amounts shy away from the political risks involved. Secondly, there are massive operational risks that are not easy to surmount.

In the end, therefore, the fabricated monopoly will turn into a hustler extortionist leveraging an undeserved license for a quick buck. Such short-termist incentives will mean de-scaling, fragmentation, talent retrenchment, value balkanisation, and ultimately profit-attrition for all industry players, except for the racketeer. For consumers, the result will be a far worse service level at a considerably higher cost than they have become accustomed.

5. Consumers will be worse off for it (FAIL)

Should the sequence above materialises (and our hope is that it tumbles at floundering stage and that national rollout doesn’t happen), the telecom industry in Ghana will be saddled with the chronic effects of underinvestment in the latest technologies for many years to come.

Lower investment and outdated technology will exacerbate the very problems the government claims it aims to address: uneven telecom coverage across the country, higher pricing, lower quality, and stifled innovation.

Way forward (avoiding the 5 Fs)

Any half-attentive reader should by now have realised that the situation in Ghana’s telecom sector is far more complex than the simple diagnoses and self-serving prescriptions offered by the government to date. Despite regulations meant to advance competition, market forces in the current climate have not led to benign outcomes.

Understanding how to engender sound competition requires a thorough study of why current regulatory models have failed. Only then can the proper role of government in fixing the deep, structural, issues at play be discerned and incorporated into policy.

There is much that Ghana can learn from countries like the Philippines that are economically more advanced than it is in certain respects but still confront similar challenges. The Philippines’ Open Access policy framework lays out nearly identical challenges as those bothering Ghana with dominant incumbents and high barriers to entry and scaling for smaller players.

The strategies for dealing with these challenges, as specified in the Philippines’ model, however, include strong enforcement of rules requiring incumbent telecom operators and tower owners/lessors to grant access to base/backhaul/backbone infrastructure on fair, reasonable, and non-discriminatory grounds. Outmoded spectrum rules that fail to recognise the technological convergence underway in telecommunications are also identified as requiring urgent changes.

It is a shame that in Ghana virtually no policy debate along such lines is even taking place, and that the government is instead jumping straight into creating a new monopoly infrastructure provider with absolutely no public documentation on exactly how this entity will address any of the specified causes of the current industry challenges.

As the GSMA has strenuously warned, national single wholesale infrastructure strategies are neither popular nor proven.

The few global experiences studied by industry experts similar to what Ghana is attempting, with much less savvy to be honest, do not inspire confidence.

In fact, five years after attempting this experiment, Rwanda, the country that went the farthest down that path, backtracked.

There are multiple approaches to promoting healthy competition for consumer benefit and industry progress, the challenge is the right calibration of the right tools for the right moment. The complexities of modern technology have thrown wide open many of the old questions about monopoly, market competition, and how to define them. Policy thinkers around the world are grappling with these difficult realities and scratching their heads for solutions.

One thing is however for sure. Half-baked, crony-empowerment, schemes are, definitely, not a substitute for the hard work required.

Opinions of Monday, 10 June 2024

Columnist: Bright Simons