During a recent visit to Ghana, I travelled on the Accra-Kumasi road on several occasions. My observations on the reconstruction section between Achimota and Ofankor have obliged me to share some thoughts in these pages. As a precursor to the issues to be discussed, I would digress into worth-mentioning aspects on road infrastructure reconstruction that may aid in the appreciation of the subject matter.

Infrastructure is the bedrock of development and comprises the fundamental facilities and systems needed to sustain economic growth. Ghana’s private and public infrastructure such as roads and highways, communication systems, commercial and residential properties are undoubtedly booming. Growth prediction in this sector is positive and the possible injection of capital from the emerging oil industry has the potential to provide additional resources to accelerate the pace of growth.

There is a genuine determination to redevelop our ageing road infrastructure to match future aspirations. However, in carrying out these works, stakeholders have the moral obligation to cater for the needs of the existing road users.

In the past new roads were constructed on green fields with little or no disruption to road users. Road builders simply built roads from Town A to Town B with no reason to implement plans to cater for existing road users during construction. In recent times, road construction is merely incremental additions to the existing infrastructure with the view to increase capacity and facilitate traffic flow.

New road schemes may involve improving or building junctions on existing roads, widening or increasing the number of traffic lanes, installing pedestrian crossings, building over-bridges, installing communication equipment or upgrading underground utilities and services, etc. It is not practicable to have possession of a section of highway or render a road link virtually impassable in the name of improvement works for long periods without major disruptions and knock-on effects on the local community. Hence, traffic management techniques have evolved globally over the past few years to combat the problems of safety, congestion and environmental pollution, and to enable road works coexist with existing traffic and other forms of road users with limited disruption and discomfort.

My experience on the Ofankor-Achimota road in Accra, however, tells a different story. Our country has witnessed an explosive growth in car ownership and this has resulted in extensive traffic congestion on major roads within the big towns and cities, even in areas where no evidence of road works exists. This should make traffic management an essential planning tool for the construction projects we undertake. However, it appears this concept is non-existent in our construction vocabulary, as can be seen on the reconstruction works between Accra and Ofankor.

In brief, the proposal is to construct a 5.7 kilometre three-lane dual carriageway, incorporating three grade-separated junctions and service lanes by utilising an existing urban road and its corridors. The reconstruction works commenced in the last quarter of 2006 and was scheduled for completion in 36 months on a budget of 400.4 billion (Old Ghana) cedis. From what I saw in respect of the amount of work completed, it is most probable that the scheme will overrun the deadline by several months.

Most construction contracts include penalty clauses, otherwise referred to as “liquidated damages” that set out what compensation will be payable if one party fails to fulfil their contractual obligations or when delays occur. Incentive clauses are also available, specifically to enhance project success by rewarding contractors with an agreed percentage of the savings that accrue for early completion. I doubt if there is any interest in making someone accountable for the state of affairs on this road.

Having used the same road two years ago, I am able to state with absolute certainty that except for some retaining walls, a short length of concrete crash barrier in the central reservation and some isolated bridge columns and abutments; there have been virtually no progress in reaching the completion milestone. It is easier to describe what the contractors have achieved to-date as follows:

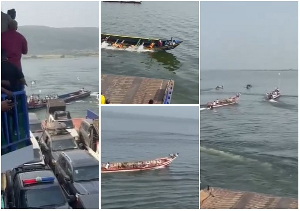

1. They have dug up the road from Achimota to Ofankor with no definitive route for road users. Drivers have to find their own way on an unbound, heavily deformed road with gaping pot-holes that are as impressive as Lake Bosomtwe, when it rains.

2. Pedestrians, including roadside hawkers and those crossing from one side of the road to the other, construction plant and equipment, long distance and local traffic, all compete for authority on the same road space. The contractors have successfully created a state of anarchy on the road with public money (or loans they have sold to us)

3. Particulate emissions – a mixture of dust and exhaust fumes dominate the air space during dry periods. The cost of prolonged exposure to polluted air on the local community (residents and businesses) may outweigh the benefits of the scheme well into the future. Is this good value for money?

4. Longer journey times, coupled with wear and tear of mechanical parts and depreciation in the value of vehicles may be a hidden component of the overall cost. Factor in driver fatigue and the natural tendency of drivers to change behaviour to compensate for lost time, and we are looking at a very high cost indeed.

Carrying out road reconstruction works in the centre of town without respecting the interests and welfare of road users and the local community is unfair. It is tantamount to social torture – taking advantage of the unwillingness of Ghanaians to challenge the status quo.

Why mess up the full stretch from Achimota to Ofankor if resources to complete the works are unavailable? It would have been easier to complete the works in smaller/shorter sections. What prevents one side of the dual carriageway from being constructed first and using traffic management techniques to control both north and southbound traffic to maintain a decent speed and riding comfort?

Elsewhere in the world, infrastructure reconstruction is a complex business. Apart from acquisition of funding, land issues, contractual and statutory procedures, there is usually the need to overcome organised opposition from environmental pressure groups and NIMBY reaction (Not In My Back Yard – term given to local opposition to development proposals that are perceived as a threat).

Infrastructure redevelopment for a nation involves capital intensive schemes, and these must be planned in a fastidious and painstaking manner with emphasis on minimising environmental and construction impacts. Such schemes must be sustainable and encourage social progress which recognises the needs of everyone. With no intention to sound like the prophet of doom, my crystal ball tells me that unless we tread carefully, NIMBYism would take root in our communities.

Albert Kontoh UK based Chartered Civil Engineer

Opinions of Monday, 7 September 2009

Columnist: Kontoh, Albert