The national discourse that has ensued over the legacy of former President JJ Rawlings following his death on November 12th 2020 is hardly surprising given his enigmatic nature during his twenty-year rule.

While even a casual glance at the media coverage will show, many a Ghanaian has commented on various aspects of Rawlings’ legacy, there is still no consensus on what exactly our former president left behind for present and future generations of Ghanaians.

My aim in this piece is to take one aspect of governance under Rawlings, that is whether or not he was tolerant to dissenting views as a leader, and in this case his willingness or otherwise to engage on a critical issue as human rights violations during his administration. This is my modest contribution to the raging national discourse about the legacy of the man.

As a preface to this write-up on the issue of human rights under Rawlings, I must hasten to mention the fact that elsewhere I have examined his rule in much more detail by examining the impact on workers’ rights of the Structural Adjustment Programme (SAP) that he superintended between 1982 and 1992. So, in this piece, I want to recount an interesting and memorable encounter I had with President JJ Rawlings, as he then was (hereafter the President) in 1995 in Dakar Senegal.

The significance of narrating this public encounter is that it sheds some light on possibly another facet of the man: As a leader who could entertain very critical views about his leadership on politically sensitive issues such as the reported cases of human rights violations during his time in office.

Since the demeanour of the man during this encounter with him was a pleasant surprise to me, the question I invite the reader to help answer is: Was his attitude and behaviour a public political gimmick or was the man very tolerant of dissenting views?

This encounter I had with the President was so momentous that a renowned Ghanaian Diplomat, Ambassador D.K Osei, in his memoir titled, Privileged Conversation: Adventures of An African Diplomat, published 2020, devotes a couple of paragraphs in discussing the implications as he saw it.

In 1995, the president was on a state visit to Dakar, Senegal. Those who accompanied him on this trip that I knew and I can recall were one Ambassador Kortei( apparently, a brother to the General Kortei, who was one of the Generals executed in 1979), Professor Kwamena Ahwoi, Ambassador D. K Osei and Dr Ibn Chambas.

The president’s visited coincided with my recruitment as a junior Visiting Research Scholar researching “aspects of application of human rights law to academic freedom in Africa” under the auspices of CODESRIA, the progressive Pan African research organization headquartered in Dakar.

I was invited to the event by a friend and a respectable Ghanaian scholar by the name of Dr Akwasi Adu, Director IDRC, who lived in Dakar at the time. When we got there the mood was very cordial and friendly; really Ghanaian.

After the usual exchange of pleasantries, the President was formally introduced after which he made a very eloquent and impressive off-the-cuff speech. Citing several specific examples to illustrate his point, he spoke about the positive developments that have taken place in the country since he assumed power in 1982. He also touched on the return to constitutional order. In fact, the speech was greeted with a standing ovation by the audience.

During the question and answer session, most of the questions and comments centred around immigration challenges faced by some of the Ghanaians residents in Senegal, while those who dared ask questions about political matters at home dealt with “low hanging fruits” that were soft and non-contentious.

As an afterthought, I suspected that having observed that the comments and questions were generally complimentary to his Excellency, the president I was readily given the chance to address him by officials of the Ghana mission when I indicated my intention to do so.

At this point, I told the President that I will make an observation and then follow it up with a question. Specifically, I began by

posing a rhetorical question as to whether his government had traded off human rights for the IMF & World Bank-inspired neo-liberal economic development paradigm. The premise of this question was his earlier account of the successes chalked by the PNDC/NDC government in the economic domain.

Following this question, I paid a glowing tribute to him for the laudable progressive principles he had introduced into the Ghanaian political economy when he initially took power. However, I added that “as a young student, Mr President, I parted company with you once there were reliable accounts of serious human rights violations, in particular, the extrajudicial executions”.

It is needless to say that I had my facts having researched the subject of human rights subject for some time. In fact, I listed and cited my sources of reported cases with figures of political prisoners, enforced disappearances, torture, extrajudicial executions.

In my presentation, I made a nuanced distinction between the violations of 1979 which as I argued there was some complicity from sectors of Ghanaian society, for example with slogans of “let the blood flow “ and others, from the post-1981 violations.

As I was building my case of human rights violations under his watch, I saw a tall officer, certainly not Senegalese security, but a Ghanaian, approaching me from behind. I paid him no attention because I knew it would be stupid for him to even touch me in the glare of the Senegalese and Ghanaian media.

When the President saw the security officer got closer to me, he shouted, “do not touch that young man, these are the bold people I need in my country”. After this admonition, the security officer shamefully walked away. However, behind me, I could hear the then Ambassador DK Osei, whisper something to the effect that I should be less critical.

With the benefit of hindsight, when I had the floor, I do not think I said anything extraordinary or anything that was not in the public domain. Rather, I suspect that the concern of the intelligence officers, political advisors and the protocol/diplomatic staff was that they did not foresee such situation to have prepared the President to deal with adequately.

In all fairness to the President, he ensured that no one disturbed me when I was raising the difficult issues and he gave me all the attention, listening attentively. In fact, the whole gathering that was noisy and chatty before my encounter with the President, went dead silent, to the extent that a drop of a pin could have been heard.

Once was I done, Dr Ibn Chambas, then Deputy Minister for Foreign Affairs, stood up to attempt to respond to me, then the President sprang to his feet like a splitter and said in his usual dramatic self with a loud voice, thus “ Chamboo, that is for me, and not you; leave it for me to respond”. After this intervention, Chambas beckoned to the President to speak.

In his answer to my question, the president began: “Young man, let me teach you some psychology. Do you know I was not in charge of the forces during the period in question”? He then disclosed that he was as often in Gondar barracks but the other ranks forced him to undertake the acts ( read violations) that I was attributing to him or his leadership.

The president then illustrated his point with the analogy of holding matches at a gas station and one is being pushed to light it but he as the holder is resisting the action. This, according to him, was what happened at the height of the revolution, and had he not resisted, the executions or the violations would have been worst.

Frankly, his response was a long winding rigmarole because I supposed my question was unexpected with no rehearsed answer by his handlers. But, his body language and his willingness to engage with the question, gave the impression of someone who spoke from the heart. Nor did he construe my analysis as impudence, nor did I intend it to be. It was, as I always do, speaking truth to power.

When he ended his long response, he looked at me and asked me loudly, “do I make sense to you, young man?”, to which I politely responded, “Your Excellency, I respectfully “agree to disagree with you”. My response led to him retorting with the exclamation, “gush”!

At this point, Professor Kwamena Ahwoi and the TV crew from Ghana asked for my name after which I saw fingers pointing in my direction.

When it was all done and the president and his entourage were about to leave for the Presidency,- (of President Abdou Diouf) one of president Rawling’s handler told me that His Excellency President Rawlings wanted to me to join him in the dinner at the said presidency. I respectfully declined this invitation because I had another engagement that evening. I sensed that the president really wanted to convince me about the truthfulness of the explanation he had given me at the event.

My encounter with former President Rawlings that day gave me the impression that Rawlings was a feared leader by many but maybe the man was tolerant of opposing views. He never construed nor did anything to suggest that he saw my observations as impudence, but rather encouraged it. The question for posterity to answer after the dust following his death has settled is: Was it his usual leadership style or was it just that day?

Opinions of Thursday, 4 February 2021

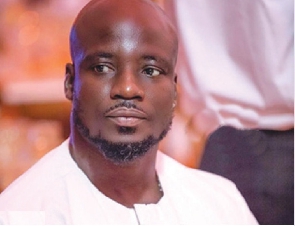

Columnist: Nana K A Busia Jr.