It comes to a point in every discerning person’s life where you begin to feel in the core of your being that some things are simply not right. Hence, the agitation for fairness, equality etc. – all summed up in one word, Freedom; that is, the attainment of independence through which a nation and its people could attempt to chart their own course – for better or for worse.

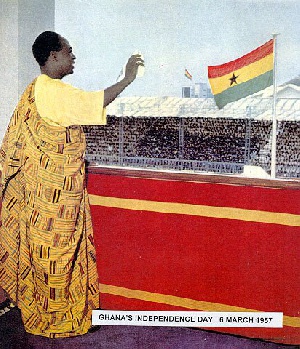

Having led the successful struggle for the independence of Ghana in 1957 – and many parts of Africa following his example – Nkrumah could not conceive of the day when he would cease to be identified with Africa, and Africa with him. It was a tall order, but history has borne him out.

Kofi Annan reflects on Nkrumah

Kofi Annan was to reflect in his memoirs “Interventions: A Life in War and Peace” that “As in many other African colonies, it was soldiers returning from the Second World War, who had served in the British army, who began to question more fundamentally the iniquities of colonial practices. They witnessed white British soldiers alongside whom they had fought and bled receive generous pensions, land, and other benefits in Africa – none of which were available to Africans. Together with leading members of Ghana’s professional classes – lawyers, doctors, and engineers – these veterans began a campaign for independence.”

The group formed “the United Gold Coast Convention (UGCC) as their party, and decided to appoint as secretary a fiery, courageous activist, Kwame Nkrumah. A member of one Ghana’s smaller tribes, and the son of a village goldsmith who had gone on to educate himself in the United States and Britain, Nkrumah brought to the cause an impatience and a passion that could not, in the end, abide the gradualist tempo of Ghana’s elite. He broke away from the UGCC to found the Convention People’s Party.”

Annan asserted that “Nkrumah possessed more than just impatience, however; he had a keen strategic mind and an ability to organize people that far surpassed that of his former colleagues. He soon became the indisputable driver of Ghana’s independence.”

Annan himself was deeply influenced by Nkrumah and wrote, “I was emotionally drawn to the passion and urgency of Nkrumah’s calls for ‘Independence now.’ Some of the statements that he was making – that we must stand on our own, that we must have our destiny in our own hands – resonated deeply with me.”

The sparkling visions of Nkrumah

In citing Nkrumah’s genius in modeling Ghana for the larger African continent, I wrote in my book, “Leadership: Reflections on some movers, shakers and thinkers”, that, “Today, the sympathies of the modern world, including many of its advanced thinkers, are powerfully attracted to the sparkling visions of Africa’s key philosopher and freedom fighter.”

In hindsight, some discerning Ghanaians may remember that “in lieu of the huge food import bills consuming Ghana’s foreign exchange today, Nkrumah had back in the day made bold allowances to make Ghana self-sufficient in grain, meat, vegetables, sugar, and important staples; in lieu of the mass youth unemployment he had initiated a workers brigade to spur young people for the world of work.”

And “to advance functional education he had initiated free compulsory education, mass education, teacher training, and science and technology; to lift high the flag of Ghana, he had originated the Ghana Airways and the Black Star Shipping Line; in short, whatever mattered, he had thought, planned, and taken direct action. Here was a leader, prescient, selfless and committed; when comes another?”

I noted that “The life of Nkrumah is modern Africa’s history. He was the battle hardened mover and shaker and the cornerstone on which the continent’s future depended. African and Pan-African issues were his issues. No matter what lightnings flashed, he knew exactly where he stood with every thunder that jolted any part of the continent.”

The Autobiography of Kwame Nkrumah

As one noted historian put it, there are certain things that can’t be stated simply: they must embody a living force in situation, character, and theme. Only a literary giant could illuminate for the modern eyes the witty scenes, dialogue and gestures appropriate for dramatizing subtle aspects of “Ghana: The Autobiography of Kwame Nkrumah,” especially the scene where Nkrumah – finally – paced into the Christiansburg Castle and met the outgoing colonial governor, Sir Charles Arden-Clarke, eye to eye, jaw to jaw.

The two had been opposing each other for so long, and were now unhinged to pluck it out. The mutual feelings of suspicion and discomfort filled the inner spaces between the British Goliath and the African David. Only a literary giant could render the vanities of mighty nose-in-the-air figures who float upwards only to be borne crashing down by the winds of change, in sync with Bob Marley’s lyrics: “If you’re the big tree, we’re the small axe, ready to cut you down.”

Fighting the reactionaries

From the very beginning, Nkrumah had to fight on four fronts. Firstly, the colonial governments which he called imperialistic parasites sucking the life blood of the African continent. Secondly, the educated elite whom – he noticed – were more British than the British themselves and could hardly feel the pain of their poorer uneducated compatriots. Thirdly, the traditional chiefs who sold the nation’s natural resources for a pittance and kept their people uneducated, and whom he threatened “would run away and leave their sandals behind them.”

Lastly, he was incensed by the religious bodies whom, he held, were so saturated by the trials and tribulations of ancient biblical characters, but paid no heed to the trials and tribulations of their own kith and kin in real time. For Nkrumah, heaven could wait so that Ghana could seek first the political kingdom.

Email: anishaffar@gmail.com

Opinions of Tuesday, 18 September 2018

Columnist: anishaffar.org