Journalist Umaru Sanda Amadu rightly asserted his rights the other day when he refused to be bullied by police officers who abused the uniform in the name of conducting a search on him.

We must all submit to law enforcement, for in doing so, we secure our own and collective security and protection. In fact, we are expected to do the good-citizen duty by alerting police and assisting them to rid our communities of criminal elements.

We must, however, not allow any person in uniform to resort to degrading and unlawful means while on a frolic and seeking to abuse our human rights in the name of law enforcement. If we allowed such unlawful arrests and searches, we will soon regret it. Misguided elements in uniform would plant contrabands on innocent persons so they could turn to arrest, search and implicate them.

Criminal elements in uniform and their collaborators would embark on a robbery mission, enter our homes, offices, shops and cars in the name of conducting searches. Terrifying stories have been told of some who allegedly ransacked homes and offices, seized, stole and even shot at helpless people and bolted without a trace, all in the name of a security operation.

There is a good reason why the police power to search without a warrant from a court is not the norm but an exception. This exception guided by the law is that there must be “reasonable cause” but not any flimsy, whimsical or malicious motivation. One definition of reasonable cause is a state of facts warranting a reasonably intelligent and prudent person to believe that a person has violated the law.

It must be based on objective and articulable facts. Our law says a police officer can search you without a warrant only where he or she has reasonable cause to believe that something that has been stolen or unlawfully obtained or about which a crime has been, is being or about to be committed, is being conveyed, concealed, etc (Section 93 of Act 30).

There is a reason, by our Constitution (Article 18(2), you lose the privacy of your home, property, correspondence or communication only under circumstances including for the prevention of disorder or crime. It is a standard procedure that the police must approach and deal with you politely as the search could result in arrest and seizure.

I was glad to hear the head of education, research and training of the police MTTD, Supt. Alexander Obeng confirm this and that people have a right to record the encounter. Sadly, here in Ghana, police conduct searches leaving their fingerprints on everything they touch. Recently, the Ontario Court of Appeal made nonsense of two cases by reversing convictions because police failed to follow the basic procedure of informing a suspect of his rights before questioning him even with a search warrant in hand.

He made self-incriminating statements, was arrested and questioned despite asking to first see a lawyer. This other person was stopped over a broken license plate. But smelling marijuana, he was searched and several cell phones, cannabis and ammunition found on him. He admitted to carrying a gun. He was stripe searched, arrested and questioned.

Prosecution admitted they breached his charter rights by their conduct and searching his phone without a warrant. The Canadian law and procedure is the same as pertains in Ghana. Cooperate with lawful searches with or without a warrant, but is not a crime to insist on the standard protocol and dignifying treatment as required by the Constitution (Article 15(1)). That’s your legal light.

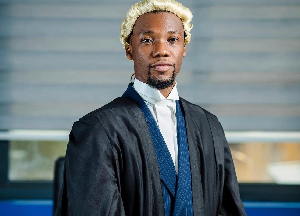

Samson Lardy ANYENINI

January 23, 2021 – Issue #2

Opinions of Sunday, 24 January 2021

Columnist: Samson Lardy Anyenini