When Ghana discovered oil in 2007, some observers predicted "Dutch Disease" as likely to hit the country in the following years.

“Dutch Disease”, a term coined in 1977 by economists as a variant of the broader concept of “resource curse”, is often used to describe the situation where a country suffers various harms, instead of the expected prosperity, after discovering and commencing production of a large stock of natural resources.

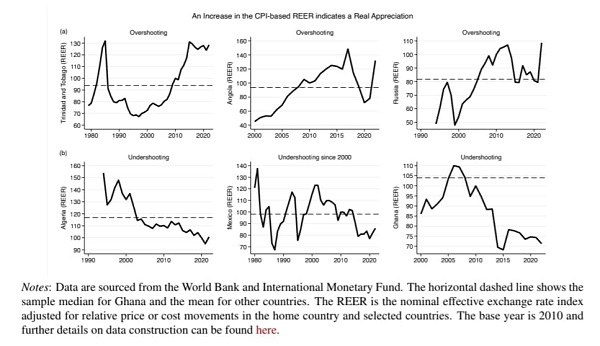

In new research by Professors Colin Constantine of Cambridge University (UK) and Tarron Khemraj of NCF (USA), evidence brought to light show that the classical Dutch Disease has not manifested in Ghana after nearly 15 years of oil production.

The classical Dutch Disease proceeds as follows:

- Country X discovers oil (or other major tradable natural resource); - A sudden surge of exports generates massive forex inflows; - Country X’s currency strengthens; - Imports become cheaper, undermining some local industries; - There is a shift of resources and emphasis to the new oil sector; and - Legacy industries suffer bringing the economy under pressure, and even to the brink.

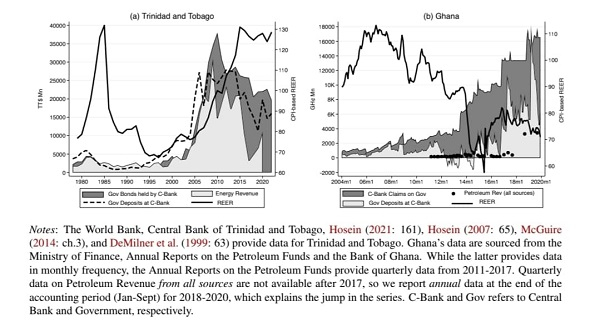

Constantine and Khemraj provide elaborate analysis in their new preprint (https://www.researchgate.net/publication/381954243_The_Monetary_Aspects_of_the_Dutch_Disease) to show that this sequence doesn't apply in the case of Ghana. It does fit the case of Angola though. As well as Trinidad and Tobago's.

Whilst the analytical reasoning applied in the paper is relatively complex, and for reasons of space and the general audience at which this brief comment is targeted, can only be massively and crudely summarised, the key insights are fascinating nonetheless.

For instance, Constantine and Khemraj argue that in a liberal economic setting where imports can flow without too much friction, a surge in forex inflows from resource exports should ordinarily not trigger the first step in the sequence: over-valuation of the currency.

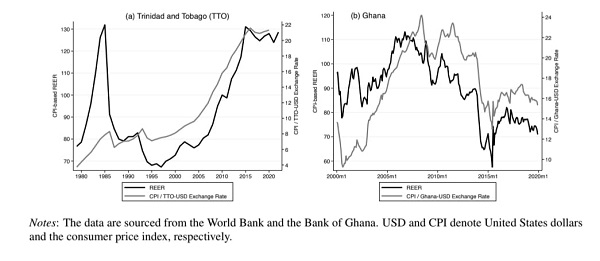

In Ghana’s case, however, very high tariffs, persistent devaluation, and consistent current account deficits (sometimes complicated by improving terms of trade) all regularly sit side by side confusing the picture of what is going on.

What is amply clear in the paper, nonetheless, is the fact that in Ghana's case (as also in Algeria and Mexico), new oil finds have coincided with a protracted record of exchange rate depreciation. Ghana's situation, even compared to other countries in a similar boat, is truly alarming. Since it became an oil producer in 2007, the national currency has fallen by over 93% in value.

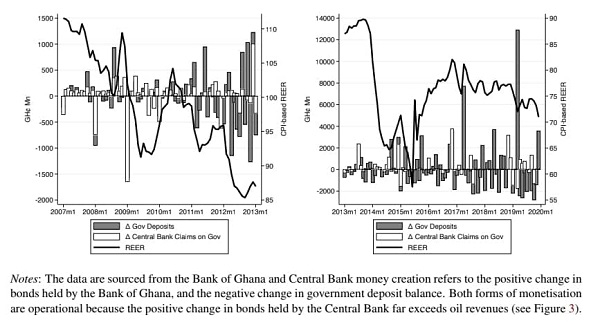

The Constantine & Khemraj paper spotlights one important cause of the Cedi's precipitous decline: the role of the Central Bank in the "monetisation" of the fiscal deficit.

Fiscal deficit monetisation came up in the discussions during 2022 when the Ghanaian currency lost more than 50% of its value in less than a year. However, this paper is one of the few empirical investigations into the interconnected variables at the root of the phenomenon, even if its focus was not on the acute factors that precipitated Ghana's debt default, runaway inflation, and currency near-death spiral in 2022, and is instead on the long-term currency movements linked to the fiscal and current accounts.

Whilst the paper does require a careful analysis of the relations among such important macroeconomic indicators as bank credit, government deposits, and resource rents, the emphasis on central bank behavior will find perfect resonance with the mood of analysts and activists in Ghana who have been sceptical of the policy conduct of the Bank of Ghana.

My personal view is that the scale and maturity of the oil industry in case study countries could also have an interesting role to play in whether monetary outcomes result in distortive appreciation or depreciation of the currency in the wake of oil finds. Still, any rigorous work that shines much needed light on the Bank of Ghana’s role in these times is a vital contribution to the conversation.

Opinions of Sunday, 14 July 2024

Columnist: Bright Simons