Recent incidents of vehicle-pedestrian collisions on the main Madina-Aburi Highway have brought to the fore the long-muted conversations around footbridges on our highways.

Our thoughts and prayers are with the families, friends, and acquaintances of all those who have for reason of sheer neglect, recklessness and irresponsibility lost their lives on this stretch of road.

We also remember all road users in different parts of the country who have for similar reasons lost their lives. May their gentle souls find solace in eternal rest!

No life should be lost under any such circumstance; a life lost this way is one too many and should be that which challenge our collective consciences and resolve to do more to prevent such happenings.

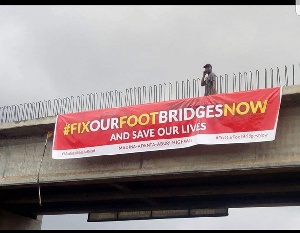

It is precisely for this reason that the recent spate of fatal vehicle-pedestrian collisions on the Madina-Aburi highway was met with spontaneous and near-violent reactions which very aptly reflected people’s indignation. Build Our Footbridges now! was the battle cry during those days of melancholic agitations and the cry has since become a mantra which the government has, seemingly, responded to with some urgency.

To build or not to build is no longer a question; it is matter of when and as we wait for the eventual completion of those bridges, it is also important that we, as a people, have some honest conversations around some underlying socio-cultural issues that make footbridge patronage such a problem in Ghana.

The current expectation is that government will fulfill its obligation and complete all the abandoned footbridges on the Madina-Aburi stretch to possibly end the rampant incidents of tragedies we have been witnessing.

While this is a welcome expectation, it is important also to recognize and acknowledge the possibility that, perhaps, the fixing of the bridges may not necessarily signal the end of vehicle-pedestrian collisions on these roads. This is because of a combination of factors which includes habits, cultures and attitudes which, somehow, are often ignored or misjudged in engineering processes and in broader discussions around footbridges.

Habits, Culture and Footbridges

Footbridges and other road crossing facilities everywhere in the world have underlying sociological and cultural factors that are critical to the success or not of patronage.

Here in Ghana, it is fair to say that the idea of the footbridge is alien and relatively recent addition to our road usage culture.

Even though most people living in busy urban communities have accepted their presence on some roads, patronage of such facilities has been worryingly low and it is not without reasons.

With the exception of the Kaneshie footbridge which is one of the earliest in the country and one that has seen relative success in patronage, most of such facilities in and around Accra have been poorly patronized.

Low patronage of footbridges is not simply because pedestrians do not want to use them, it is also not because the bridges are not conveniently located, but mainly because most people are yet to come to terms with the usefulness of footbridges as a road safety mechanism.

Pedestrians’ decisions on whether to use footbridges or not and also on where to cross a road usually involve a combination of judgment decisions.

These decisions are usually steeped in personal habits, attitudes, cultures and situations and most often comes with trade-offs between safety, convenience and risk.

The option for pedestrians to cross away from designated footbridges increase the risk of vehicle-pedestrian collisions. This is a fact that has tragically been proven many times on the Aburi-Madina stretch and on many roads in the country.

It is also a fact that suggests that the choices and decisions pedestrians make regarding where and when to cross on these roads depend not only on the convenience of the location of footbridges but also on other factors.

As a people, it is our cultural habit to carry heavy loads either on our heads or on other parts of our bodies. Women, in particular, carry children at their backs while carrying other loads on their heads.

These are cultural practices that are deeply entrenched in our everyday behaviors. They are practices that one way or the other make the choice of going up on flights of stairs and onto elevated footbridges not only tedious but also a deterrent.

For most people, climbing onto footbridges to cross a road is seen more as a punishment than a safety issue; they will rather make the obvious risky choice than to subject themselves to what they may consider an ordeal.

It is inherent in these factors and of course the judgement choices that pedestrians make with regard to road crossing that the reality of how habits and cultural behaviors impede people’s abilities and willingness to patronize footbridges become apparent.

It is also the reason the mere fixing of those footbridges on the Madina-Aburi highway may not necessarily end vehicular assaults on human lives on the roads.

The bridges will undoubtedly help; they will challenge changes in social behaviors and attitudes of people and if that ultimately reduce or eliminate such horrendous tragedies on our roads fair enough.

However, it is important that as we shout out to government and city authorities to fix our bridges now, we should not lose sight of other socio-cultural imperatives that undermine the social purposes footbridges are to serve.

Any serious conversation around the safety assurance and effectiveness of footbridges on our roads cannot ignore some of our social behaviors and attitudes.

These attitudes, ultimately, become an engineering issue which requires that our engineers who design and construct these footbridges should necessarily consider some of these socio-cultural factors not only in the design and construction of the bridges but also in the search for culturally-responsive alternatives.

Footbridges or Underpass?

It is clear, therefore, that there are cultural dimensions to our appreciation (or not) of the benefits and convenience of footbridges as a road safety facility.

It is also clear that even though the current expectation is for government to fix the numerous uncompleted footbridges within the shortest possible time, this might not necessarily be the ultimate solution to vehicle-pedestrian collisions on our roads such as the Madina-Aburi stretch.

This, however, is not to downplay the usefulness or importance of footbridges on our highways but to suggest that we may need to look at alternatives beyond our rigid engineering obsession with footbridges.

The position here is to support current government efforts to complete the long-abandoned footbridges. That said, it is also the position that such efforts should not be driven hastily by emotions and a desire to respond to people’s agitations, but by an honest commitment to do what is right for the people.

Completing the footbridges is the right thing to do, but we could also begin to explore other innovative alternatives such as under-road tunnels and pedestrian underpasses.

Pedestrian underground tunnels have been used in other jurisdictions with significant successes in preventing or reducing pedestrian-vehicular accidents. They provide the much-needed convenience and confidence needed to avoid risky choices.

Undoubtedly, tunnels or pedestrian underpasses may also come with their unique set of risks and challenges, but that should not be a reason not to at least explore their suitability to our context.

Our cultural circumstances and social attitudes will forever make the patronage of footbridges problematic and in underpasses, we may at least have an alternative.

Any argument about cost of construction of such a facility should be secondary and immaterial. The real cost of losing a life, and in the Madina-Aburi case numerous precious lives, should almost immediately mute that argument. Let the engineers tell us how possible (or not) this is.

The author is an Environmental Learning and Climate Adaptation Specialist and a Research Fellow at the Center for Climate Change and Sustainability Studies at the University of Ghana. bobmanteaw@yahoo.com.

Opinions of Sunday, 6 January 2019

Columnist: Dr. Bob Offei Manteaw

![NPP Flagbearer, Dr. Mahamudu Bawumia [L] and NDC Flagbearer John Mahama NPP Flagbearer, Dr. Mahamudu Bawumia [L] and NDC Flagbearer John Mahama](https://cdn.ghanaweb.com/imagelib/pics/869/86902869.295.jpg)