As I sit in my study in Melbourne, Australia, on this crisp autumn morning in 2024, my thoughts drift back to Ghana, the land of my birth. The debate raging there about the true founder of the nation has reached even these distant shores, prompting me to reflect deeply on my homeland's journey.

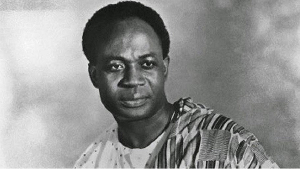

Every 6th of March, without fail, I find myself glued to my television screen, watching grainy footage of Kwame Nkrumah declaring Ghana's independence. "At long last, the battle has ended! And thus, Ghana, your beloved country, is free forever!" His words, even through the crackle of old recordings, never fail to send shivers down my spine. It's a bittersweet moment, filled with pride in how far we've come, yet tinged with thoughts of what might have been.

The Ghana I see today, through the lens of news reports and conversations with family back home, is a nation still grappling with the legacy of its first leader. Nkrumah's vision, his triumphs, and yes, his missteps, continue to shape our national narrative in ways both obvious and subtle.

Nkrumah's achievements were, without doubt, monumental. He not only led Ghana to independence but did so with a pan-African vision that inspired liberation movements across the continent. His famous declaration, "The independence of Ghana is meaningless unless it is linked up with the total liberation of Africa," resonated far beyond our borders.

In a world still dominated by colonial powers, Nkrumah dared to dream of an Africa united and strong, capable of standing toe-to-toe with global superpowers. I often wonder how different our economic trajectory might have been had Nkrumah opted for a more balanced approach. Perhaps a mixed economy, blending state planning with market dynamics, could have provided the stability and flexibility needed for sustainable growth.

The sight of abandoned factories from Nkrumah's era, now being repurposed by innovative start-ups, serves as a poignant reminder of both the aspirations and limitations of his economic vision. Yet, it's in the implementation of this vision where the cracks begin to show. Nkrumah's embrace of socialism, while understandable in the context of the time, led to economic policies that would haunt Ghana for decades.

The state-controlled economy, designed to rapidly industrialise the nation and free it from neo-colonial influences, instead created inefficiencies and stifled the very entrepreneurial spirit that might have driven genuine economic independence.

The economic legacy of Nkrumah's policies is particularly complex and deserves closer examination. His ambitious industrialisation programme, symbolised by projects like the Akosombo Dam, aimed to transform Ghana from an exporter of raw materials into a modern, diversified economy. However, the focus on large-scale, state-run enterprises came at a significant cost.

The agricultural sector, the backbone of Ghana's economy, was neglected in favour of rapid industrialisation. This led to a decline in cocoa production, Ghana's primary export, and created food shortages that the country had not experienced before independence. The government's control over pricing and marketing of agricultural products discouraged farmers and led to a drop in production.

Moreover, the emphasis on import substitution industrialisation (ISI) proved problematic. While it initially led to the creation of new industries, many of these were inefficient and relied heavily on imported inputs. This strategy, combined with expansionary fiscal policies, led to severe balance of payments problems and mounting external debt.

The nationalisation of foreign-owned companies, while popular at the time, deterred foreign investment and deprived Ghana of much-needed capital and expertise. The state-owned enterprises, often run more for political than economic reasons, became a drain on the nation's resources.

By the time Nkrumah was ousted in 1966, Ghana's economy was in dire straits. Foreign exchange reserves were depleted, inflation was soaring, and the country was deeply in debt. The economic challenges born in this era would plague Ghana for decades to come, necessitating painful structural adjustment programmes in the 1980s and beyond. Yet, it would be unfair to lay all of Ghana's economic woes at Nkrumah's feet.

His policies must be understood in the context of the time – a period when many economists believed that state-led industrialisation was the quickest path to development. Furthermore, some of his projects, like the Akosombo Dam, have provided long-term benefits to the country.

Politically, Nkrumah's legacy is equally complex. His transformation from champion of independence to authoritarian leader is a cautionary tale that continues to resonate in African politics. The Preventive Detention Act, which allowed for the imprisonment of political opponents without trial, cast a long shadow over his democratic credentials.

Yet, it's overly simplistic to paint Nkrumah as a typical dictator. His actions were driven not by mere self-interest but by a genuine, if misguided, belief that only through centralised control could Ghana achieve the rapid development it needed. This tension between visionary leadership and authoritarian tendencies is one that Ghana, like many African nations, continues to grapple with.

When I look at our political landscape today, I see echoes of Nkrumah's approach—both positive and negative. The desire for strong, transformative leadership often clashes with the need for robust democratic institutions and checks on power.

As I reflect on this complex economic and political legacy from my home in Australia, I'm struck by the parallels with other post-colonial nations. The challenge of transforming an economy shaped by colonial interests into one that serves the needs of the newly independent state is one that many countries have struggled with.

Looking at Ghana today, I see a nation that has learned hard lessons from its past. The shift towards a more market-oriented economy in recent decades has brought significant growth. Yet, the debate over the appropriate role of the state in the economy continues, echoing the tensions present in Nkrumah's time. What's particularly fascinating, and perhaps troubling, is how the debate over Nkrumah's legacy has become a proxy for larger discussions about Ghana's identity and future direction.

Those who champion Nkrumah as the sole founder of Ghana often advocate for a more state-led approach to development and a foreign policy emphasising pan-African cooperation. On the other hand, those who insist on recognising the Big Six collectively tend to favour more market-oriented economic policies and a more balanced approach to international relations.

This polarisation, I fear, does a disservice to the complex realities of our history and the nuanced approach needed for our future. The truth is, Ghana's founding was neither the work of a single messianic figure nor a simple committee effort. It was the result of a broad movement, with leaders playing different but crucial roles.

Nkrumah's dynamism and vision were essential, but so too were the foundational efforts of figures like J.B. Danquah, Edward Akufo-Addo, and others. As Ghana continues to evolve, facing new challenges from climate change to technological disruption, the real honour we can pay to Nkrumah and all those who fought for our independence is to approach nation-building with the same courage and creativity they showed, but also with the wisdom gained from their experiences.

From my vantage point in Australia, I see a Ghana that has the potential to be a leader in African democracy, innovation, and sustainable development. To realise this potential, we must be willing to engage critically with our history, learning from both the successes and failures of our founding fathers.

As I conclude these reflections, watching the sun rise over Melbourne's skyline, I'm filled with a sense of both nostalgia and hope for my homeland. The challenges Ghana faces are significant, but so too is the resilience and creativity of its people. It is this spirit – the same spirit that drove the independence movement – that will write the next chapters of our national story.

Click to view details

Opinions of Saturday, 17 August 2024

Columnist: Yaw Ofosu-Asare

Did Nkrumah's dream derail Ghana's future?

Opinions