There is no doubt in our minds that Dr. Kofi Boahene has a clear conscience about his grand vision for the interactive workings of diversity, and the implications of this line of progressive thinking for improving race relations and the human condition, for advancing the moral agency of his own social standing in the center of the universe of human complexity. This should be commended.

Then again Dr. Boahene, we should add, is an enlightened, keen and intelligent observer of the moral fallibility of human intentions, and therefore on account of this acknowledgement he does not take his perceived understanding of the cosmic reach of human behavior for granted. Our close reading of However Far the Stream Flows, naturally does not point to a Dr. Boahene who conventionally matches the designation of a classic essentialist critic of the many aberrations we have come to find in the galaxy of human character. He explains the concept this way (Boahene, p. 86):

“…like most Africans I had learned the challenges of social acceptance and personal safety. I had studied and seen the effects of tribal and colonial persecution in Africa, I had seen and heard about the treatment of Africans in Moscow, and now I was learning about the treatment of black people in parts of America.”

He notes elsewhere (Boahene, p. 210):

“In the early years of my career it was not uncommon for patients to cancel appointments when they found out that their specialist was black or from Africa, or just had a weird tongue-twister of a name. This came from both white and black patients, except one elderly African American man who, startled upon meeting me for his first appointment, declared, ‘If they let you in here, you must be good.’

“Prejudice, expressed and acted out, was familiar to me after so many years, first in Russia and then in the US. I had learned to shrug it off. Besides the color of my skin…”

Dr. Ben Carson’s Gifted Hands, likewise, offers a summary vista of the prejudicial designs of the mother of a patient—a child—who had wanted to scheme her way around his technical expertise and global fame with a view to creating an undisclosed disastrous problem for him, possibly to undermine his hard-won expertise, and to disgrace him in the process, but for the timely intervention of one of his proactive nurses who had known the said woman as, one who moved from one hospital to another hospital, harboring an insidious intention of creating unnecessary problems for providers.

We should point out that, whether Dr. Carson’s race factored into or influenced the woman’s hidden agenda is not an explicit giveaway in his memoir, Gifted Hands, but it is easy and even tempting to settle for this inference given the unpredictable nature of race relations in America. This does not in any way imply our ruling out any possible direct correlation between the two variables.

Dr. Kofi Boahene’s encounter with racism

Dr. Boahene recalls an embarrassing encounter with the long arm of racism when he, together with his American-born Indian friend and classmate, Lahar Mehhta, whose parents were born and raised in East Africa, and later immigrated to the US, stepped out to purchase ice cream in one of the most affluent Nashville neighborhoods. He writes that other customers stared at them when they communicated their order to the salespersons. The real surprise however came when, after he had paid for his order, the cashier dropped his change on the counter rather than in his outstretched palm.

On another occasion, he maintains, he and Mehta went to a shop and were browsing for clothes when he noticed he was being closely followed around “and furtively eyed by a store clerk” (Boahene, p. 128). He then concludes his unfortunate narrative: “‘They don’t do it with the others,’ I said. ‘Watch.’ Lehar was shocked.”

It is sad and morally objectionable to try to link criminality to race and ethnicity on the basis of mere suspicion, without the benefit of the incriminating indictment of proven or provable forensic evidence. We cannot but accept the fact that dysconscious racism, unconscious bias, ignorance, and institutional racism are to blame for most of these remarkable instances of outrageous acts, excluding the fact that racists and ethnic chauvinists destroy life while humanistic and philanthropic human beings—like Drs. Boahene and Carson—save and preserve life.

Yet we are quick to ignore the idea that racism (and ethnic chauvinism) is costly in economic terms, an excellent reason to fight it by making a concerted effort to realize this extremely difficult undertaking. Research findings indicate that racism costs the US a whopping $1.9 trillion annually while it cost the Australian economy $ 44.9 billion annually—from 2001 to 2011 (McCray, 2016).

Unfortunately there is no universally accepted consensus on how to approach the fight against racism. Frantz Fanon (2008) and Albert Memmi (1991) may have conceptualized the liberation of the colonizer and the colonized to benefit both parties. However, Dr. Boahene sees whites and blacks coming together in the spirit of solidarity, against racism. This is how elegantly he frames up his assimilationist methodology—courtesy of Cindy, his “American mother,” so-called (Boahene, 148):

“There we were,” Cindy said later. “I’m white and all dressed up like I was African. Derek’s mother, black as ebony, was wearing a beautiful Western dress, all white…”

Dr. Boahene is sounding more like the American-educated philosopher and theologian from the Gold Coast, Renaissance man Kwegyr Aggrey who was widely reported to have said the best cheerful sound from a piano only comes about if the white keys and the black keys are played together.

It looks as if Stevie Wonder and Paul McCartney are here with their classic hit single—“Ebony and Ivory.”

The Paradigm of Historical Consciousness

This brings us to the question of historical consciousness. What is it? Historical consciousness is a painstaking process, a continuous education, and not something one acquires in a fit of serendipitous momentariness. Historical consciousness is an endless journey toward a continuously evolving destination of heightened self-awareness. Historical consciousness is a heightened state of mind in that it imbues human dignity with a proactive sense of agency and location in a relativized existence borne out of the Sisyphean weight of cultural globalization.

To wit, historical consciousness is a self-correcting and self-regulating immunity mechanism against the virulent pugilistic feints of cultural imperialism. Historical consciousness is therefore a precondition for the optimal actualization, and hence attainment, of cultural and social justice in a confused world of self-perpetuating moral and ethical errancy. Dr. Molefi Kete Asante is right when he suggested that we shift the focus of public discourse from overemphasis on social justice to the paradigm of cultural justice in race relations, pedagogy and critical theory (Asante, 2017).

Dr. Asante is not however saying we cannot pursue both. We hope to see Dr. Boahene take up this challenge in his subsequent publications—the challenge of developing a more formidable historical consciousness as he extends the already-expanding sphere of his humanism and medical expertise to race relations. This comes with a better understanding of social and cultural justice.

Finally, pursuing the aims of historical consciousness means that he must become culturally sensitive to the language of public discourse and academic socialization (Asante, p. 2003; Allimadi, 2003). Some aspects of his auctorial language make him look and sound like a pampered apologist of colonialism and cultural imperialism. Here are a few notable examples, some paraphrased, others verbatim: “Ashanti” instead of “Asante,” “tribal jungle village,” “black mark,” “British colonialism was relatively benevolent,” “one positive aspect of British colonial rule,” “sub-Saharan Africa,” and “tribalism.”

The derogatory tone of his otherwise remarkable memoir is deeply worrying since, in one sense, it perpetuates the racist, Eurocentric stereotyping of Africa and its people. His is the type of language that even contemporary Western anthropology is trying so hard to distance itself from, thanks to the sound activist scholarship which Dr. Asante and others represent. Thus his writing exemplifies the elitist bias of Eurocentric paternalism. Dr. Boahene has to take a close at Chinua Achebe’s brilliant essay “An Image of Africa: Racism in Conrad's Heart of Darkness” and Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. He may also want to read Ayi Kwei Armah’s Osiris Rising for a change if, indeed, he has not done so already.

Sadly, Dr. Boahene is still imprisoned in the firm grip of the slowly dying Mesozoic era of Tarzan filmography. Perhaps he needs some grounding in postcolonial criticism and Afrocentric theory.

Dr. Kofi Boahene’s moral and historical dilemma

We are at pains to conceptualize the character of Dr. Boahene as one that is seriously conflicted. Our close reading of However Far the Stream Flows offers a striking detour into this possibility of his being seriously conflicted, one way or the other, once we noticed that his auctorial pen had attempted to rewrite or rearrange the terms of the historiography of race relations, quite apart from the underlying psychopathology of certain human behaviors. This questionable instance of historiographic schizophrenia is uncharacteristic of a rather progressive and visionary leader such as Dr. Boahene. The following statement underscores our point (Boahene, p. 87):

“I do not mention this history, and the sense of danger at the time, not to denigrate any people or communities, nor am I ignoring that things have gotten better in the past two decades. I bring it up because African American history meant something to me personally. I had grown up keenly aware that the region I come from was a slave-trading center and embarkation point to the Americas (our emphasis).”

What do we make of this internally conflicted statement? Our view is that the statement should not dissolve into a question of standing by the African-American community or by the White-American community—per se. It is rather standing by the moral weight and conscience of history that one is certain to enjoy the guarantee of absolute freedom from the demoralizing constraints of ignorance given that true, correct history does not need mortal defense of any kind before it can exert the influence of its moral conscience over the cosmic soup of human behavior. Mortals, we should add, do not write history—as a matter of fact. It is the moral conscience of humanism and social justice that we can say epitomize the true authorship of history.

We are not, however, implying that Dr. Boahene is ignorant—lest we are misunderstood, for we have made a repeated claim that he is not the kind of public intellectual that one can convincingly say is trapped in a revolving loop of endarkenment—thereby cementing his moral authority, academic credibility, and important contributions to medical knowledge. Granted, what do we make of the line “the largest single market in West Africa” (Boahene, p. 55) which also appears verbatim in the entry for the Kejetia Market in the pages of Wikipedia? Perhaps, and this is very important, we are constrained in our efforts to understand him fully or to plumb the depths of his historical consciousness by the mischievous obscurantism of his authorial erudition and medicalese.

But, why was he being naively apologetic about what is supposed to be irrefutable facts of history, though it is our understanding that one does not denigrate any community by stating the obvious? What is more, being unnecessarily apologetic about an obvious historic truth makes him look like a sneaky intellectual, although, once again, he manages to gather enough courage to fault some communities through his subtle language of diplomacy—in parts of his memoir. In this sense there appears to exist a trace of hesitant neutrality in his critical tone, and how he employs that critical tone in his critique of social and historical injustices. Dr. Boahene is one to carry the “big stick” of Malcolm X and the “carrot” of Martin Luther King, Jr. Both were critics of the establishment—the American state—and of its arbitrary deployment of the instruments of state power against defenseless citizens!

And what should we make of his “slave-trading center” reference, a reference thrown about without the benefit of a quantifying mechanism duly expressed as a function of his overt apologetic bias? A nostalgic or romantic allusion to ancestral brotherhood? Perhaps. Here he is absolutely correct in his claims to Pan-African solidarity, unless of course he is scandalously towing the questionable claims of authorial subjectivity conceptualized as a normative methodology of revisionist negationism (Gyasi, 2007; Asante, 2010). How difficult it is to accept the fact that an 18th-century Dutch-educated gentleman from the Gold Coast, now Ghana, Jacobus Captein, would use his hard-won education to support slavery, making specious arguments that Christian principles did not contradict the institution of slavery (Captein, 1999)!

It is therefore our impression that Dr. Boahene appears to have an unsettled—or unresolved—conscience on the basis of his schizophrenic approach to the troubling historiography of race relations in America. Certainly, he is torn between the lasting generosity and moral genuineness of some of his benefactors and the undeniable facts, moral weight and conscience of history (Asante, 2011). Dr. Boahene therefore faces a serious moral dilemma. It is clear also which community he does not want to denigrate. In this case he is being merely economical with the historical truth with his mischievous revisionist twist of historical facts and contemporary events—and his tactical failure to reveal the anonymous identity of this community which, we are afraid, could be his prized target niche audience. Let us snatch a glimpse of what he actually meant by the phrase “this history” (Boahene, p. 86):

“Marshall is in a remote, backwood-sy pocket of the country that, during the early 1900s, had been ethnically cleansed of African-Americans by anti-black race riots, lynchings, and the destruction or seizure of black-owned properties. In Harrison, anti-black harassment and violence between 1905 and 1909 drove all but one of its black residents out of town and out of that part of the state…”

What has happened to his location and agency? Then he writes (Boahene, p. 68): “Cindy wondered how big a problem the color of my skin might be in a town associated with the most virulently racist group in America, the Ku Klux Klan.” Dr. Boahene is clearly caught between the deadly fangs of Rudyard Kipling’s “The White Man’s Burden” and Edward Morel’s “The Black Man’s Burden.” Dr. Boahene’s skeptical optimism about—and subtle language of temperate response to entrenched problems of race relations—certainly makes for his cautious yet defensive avoidance of difficult social problems. It is the larger society, but mostly the African American community, that loses in the end.

Our impression is that it is likely he prefers to sit on the fence, although our reading of this indispensable aspect of his memoir could still be wrong, rather than wallow in the stenchy mud of race relations. But that is not how it should be! Privileged persons of his caliber should be bold to use their position of authority and influence to help reset the dial of a national conscience that has gone askew, to, as a matter of fact, benefit the larger society irrespective of creed, religion, race, and gender, and to promote humanism as well. Not too ago, for instance, the Ku Klux Klan chased one of America’s and the world’s most vibrant and promising mathematicians, Dr. Jonathan Farley, from Tennessee, even though Vanderbilt University had tenured him in 2005. Harvard’s Prof. Samuel Allen Counter, Jr., late, had this to say about Dr. Farley (Jet Magazine, 2004):

“Jonathan Farley is one of the world’s most impressive young mathematicians…He is a model of excellence for young people of all backgrounds, but especially African-Americans who may see their intellectual potential in him. Harvard is proud to honor his achievements and acknowledge his fine example.”

SPECIAL NOTE TO OUR INTERNATIONAL READERS

Readers should watch Dr. Boahene’s CNN interview here https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P_8kt6kCnLk

REFERENCES

1) Asante, M.K. (2010). Henry Louis Gates is wrong about African involvement in the slave trade. Retrieved from http://www.asante.net/articles/44/afrocentricity/ —(2011). Rooming in the master's house: power and privilege in in the rise of black conservatism. Philadelphia, PA: Routledge. —(2017). Revolutionary pedagogy: primer for teachers of black children. N.Y., N.Y: Universal Write Publications LLC. —(2000). The Egyptian philosophers: ancient Africa voices from Imhotep to Akhenaton. African American Images. —(2003). Afrocentricity: the theory for social change. African American Images, Inc.

2) Bauval, R., & Brophy, T. (2013). Imhotep the African: architect of the cosmos. N.Y., N.Y.: Disinformation Books. —(2011). Black genesis: the prehistoric origins of Ancient Egypt. Rochester: VT: Bear & Company.

3) Bernal, M. (1987). Black Athena: the Afroasiatic roots of classical civilization (the fabrication of ancient Greece 1785-1985, Volume 1). New Brunswick: NJ: Rutgers University Press.

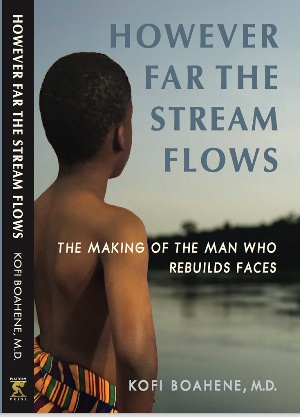

4) Boahene, K. (2016). However far the stream flows: the making of the man who rebuilds faces. Doylestown, PA: Winans Kuenstler Publishing, LLC.

5) Brown, T. (2015). The shift: one nurse, twelve hours, four patients’ lives. Chapel Hill, NC: Algonquin Books.

6) Captein, J.E.J. (1999). The agony of Asar: a thesis on slavery by the former slave, Jacobus Elisa Johannes Capitein, 1717-1747. 231 Nassau Street Princeton, NJ: Markus Wiener Publishers.

7) Carson, B., & Murphey, C. (1996). Gifted hands: the Ben Carson story. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan.

8) Chinua, A. (1977). "An Image of Africa: Racism in Conrad's Heart of Darkness." Massachusetts Review. 18. 1977. Rpt. in Heart of Darkness, An Authoritative Text, background and Sources Criticism. 1961. 3rd ed. Ed. Robert Kimbrough, London: W. W Norton and Co., 1988, pp.251-261. Retrieved from https://polonistyka.amu.edu.pl/__data/assets/pdf_file/0007/259954/Chinua-Achebe,-An-Image-of-Africa.-Racism-in-Conrads-Heart-of-Darkness.pdf

9) Chinweizu. (1975). The West and the rest of us: white predators, black slavers, and the African elite. N.Y., US: Vintage.

10) Diop, C.A. (1989). The African origin of civilization: myth or reality? Chicago, IL: Chicago Review Press. —(1991). Civilization or barbarism: an authentic anthropology. Chicago, IL: Chicago Review Press.

11) Dompere, K.K. (2017). The theory of philosophical consciencism: practice foundations of Nkrumaism in social systemicity. London, UK: Adonis & Abbey Publishers Ltd.

12) Du Bois, WEB. (1979). The world and Africa. N.Y., N.Y.: International Publishers Company Inc.

13) Fanon, F. (2008). Black skin, white masks. N.Y., N.Y: Grove Press.

14) Finch, C. S. (2000). The African background to medical science: essays on African history, science, & civilizations. Karnak House Publishers.

15) Gyasi, Y. (2017). Homecoming. N.Y., US: Vintage.

16) Haber, L. (1992). Black pioneers of science and invention. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

17) Jet Magazine. (July 19, 2004).

18) Kwarteng, F. (2005, October 8). Nkrumah’s name & birthdate are not set in Moses’ tablets of stone 1. Retrieved from https://www.modernghana.com/news/647864/1/nkrumahs-name-birthdate-are-not-set-in-m.html —(2017). Theresa Brown’s The Shift, A Review. Retrieved from https://www.modernghana.com/news/795191/theresa-browns-the-shift-a-review.html

19) McCray, R. (April 10, 2016). How racial discrimination costs billions. Retrieved from http://www.takepart.com/article/2016/04/10/cost-racial-discrimination

20) Memmi, A. (1991). The colonized and the colonizer. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

21) Milton, A. (2003). The hearts of darkness: how white writers created the racist image of Africa. N.Y., N.Y.: Black Star Books.

22) Obenga, T. (2004). African philosophy: the pharaonic period: 2780-330 BC. Senegal, West Africa: Per Ankh.

23) Raju, C.K., & Lal, V. (2009). Is science Western in origin? Penang, Malaysia: Multiversity and Citizens International.

24) Raju, C.K. (2013). Euclid and Jesus: how and why the church changed mathematics and Christianity across two religious wars. Penang, Malaysia: Multiversity & Citizens International.

25) Sertima, I.V. (1996). Golden age of the moor. Piscataway, N.J.: Transaction Publishers. —(1991). Blacks in science: ancient and modern. Piscataway, N.J.: Transaction Publishers.

26) Soyinka, W. (2013). Of Africa. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

27) Thiong’o, N.w. (2009). Something torn and new: an African renaissance. N.Y., N.Y: Civitas Books.

28) Zimmerman L., & Veith I. (1967). Great ideas in the history of surgery. Mineola, N.Y.: Dover Publications.

Opinions of Thursday, 11 January 2018

Columnist: Francis Kwarteng