BBC world affairs correspondent Mark Doyle travels to Ghana and Malaysia to compare the development experiences of nations that were roughly on an economic par 50 years ago.

I often have a familiar conversation with friends from Ghana. It goes something like this:

Ghanaian friend: "Oh, this country! Nothing works in Ghana! Why are our politicians so useless? Why are we so poor?"

Ghana got independence in 1957, as did Malaysia |

Me: "Hey! don't do yourselves down! You've got peace and democracy. You're miles better off than most other Africans. What's more, this country is full of really friendly people! "

Ghanaian friend: "Come off it, Mark. You can't eat democracy or friendly people! Anyway, why should we compare ourselves with other African failures? We want to compare ourselves with the best! We won independence in the same year as Malaysia, in 1957! How come we're not as rich as them?"

British colonial records show that in the early 1950s, Ghana and Malaysia were on an economic par - equally poor and equally dependent on the export of raw materials.

Today, Ghanaians get by on an average of about $300 per year, while Malaysians earn over $3,000. Ghana is still exporting raw products like cocoa and gold, Malaysia makes its own cars and boasts skyscrapers that rival anything in New York or London.

Stability crucial

The development of one product - palm oil - tells part of the story. Ghana grows and processes the rich red oil to make soap and cooking oil.

| Mahathir Mohamad former Malaysian leader |

Malaysia - which imported its first palm oil trees from west Africa in the 1950s - has not only become the largest palm oil producer in the world, but has also developed a high-tech industry which makes sophisticated chemicals and food additives from the raw berries.

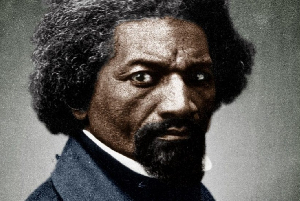

The main architect of the economic boom years for Malaysia - the 1970s and 80s - was the recently retired Prime Minister, Dr Mahathir Mohamad.

"Political stability is extremely important", Dr Mahathir told me. "Without political stability there can be no economic development. People are not going to put money into a place where there is no certainty".

Malaysia's skyscrapers rival anything in New York or London |

Mahathir Mohammed is well qualified to talk on this subject - he held power for an unbroken 20 years.

Economists and business people I spoke to in Malaysia agreed - the Malaysian state had established a solid framework of laws that allowed entrepreneurs to flourish.

The comparison with Ghana could not be more stark. In 1966, just nine years after independence, there was the first of a series of military coups which plunged the country into two decades of instability.

President John Kufuor of Ghana may have broken that pattern. He was elected in 2000 in multi-party polls which were a model of fairness and free debate, then re-elected last December to another four-year term.

Unhappy history

President Kufuor received me in the former slave and trading fort that is today the Ghanaian Presidency - an impressive white seaside building called 'The Castle'. I asked him why the coups were allowed to happen:

| MODERN GHANA  1957: Gained independence from Britain 1966: President Kwame Nkrumah deposed 1981: Flt-Lt Jerry Rawlings seizes power 1992: Rawlings voted president in multi-party poll 2000: Kufuor elected president |

"It's part of our history - our unhappy history," he replied.

"Ghana has been pushed through all types of regimes and now we've come to the point where we're saying we've tried them all and the best is democracy. Perhaps our development may not be as fast as we might want it, but with patience and persistence, life under democracy will be far better," he said.

When President Kufuor visited Malaysia recently he told Dr Mahathir about his four year terms of office.

"Four years?" the Malaysian replied, according to Kufuor; "Just four years? You can't achieve much development in four years!".

The general rule in Malaysian elections is that the government always wins. The ruling party has established a sophisticated system of coalitions (also known to detractors as 'buying off the opposition') which has given the business community the continuity it thrives on.

What Malaysia does not have, and Ghana does, are freedoms like freedom of the press.

I asked Dr Mahathir if there was a trade-off between democracy and development:

Enabling development

"Democracy is about the right to change government through the ballot box", the retired Prime Minister told me; "Liberal democracy of course goes to the extent where individuals can do anything they like. If they want same-sex marriage, well why not? If they want to walk around stark naked, that is their right.

Ghana still relies on producing primary products like palm oil |

"We don't go that far. We think the most important thing about democracy is the right to change government through the ballot box... Freedom to destabilise the country is not something that we consider as a part of democracy."

When I mentioned to Dr Mahathir that, in fact, government had not been changed in Malaysia through the ballot box, he shot back;

"That, too, is democratic, because that is the will of the people".

The sort of political stability achieved in Malaysia is not just an end it itself, but also creates conditions for other aspects of economic development - such as building roads and railways, and an education system. These various factors have re-enforced each other in Malaysia.

| |

Another critical aspect of Malaysia's development has been a large indigenous entrepreneurial class mainly made up of dynamic ethnic Chinese businesspeople. The majority ethnic Malays dominate politics and the civil service, while the ethnic Chinese tend to drive the economy.

In Ghana, by contrast - as in much of the rest of Africa - the industrial sector is dominated by the subsidiaries of multinational companies and much of the retail trade is run by immigrant Indians or Lebanese.

The relative lack of an indigenous business class means that some of the profits from these economic sectors are siphoned out of the country. The "Virtuous Circle" of substantial savings leading to investment, and so increased productivity - which in turn can lead to more savings - has yet to be established in Ghana.

Some people in Accra say that now Ghana has democracy and political stability it may start the long haul to catching Malaysia up economically.

But even the most optimistic say that if that happens, it may take a generation to achieve.