When I was in the university, I always found myself in a crisis as my exam finals approached.

I used to enter into “emergency mode,” wherein I cut 40 per cent of the study material and set a month-long schedule.

This included 10 to 12 hours studying on a daily basis and culminated in locking myself up in a cheap hotel close to the exam centre for the final week.

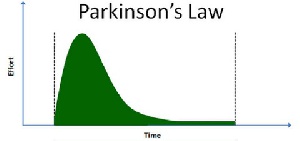

When I have too much time to complete a task, I have a tendency to procrastinate until it becomes urgent. As the deadline looms, I become hyper-productive in order to get the job done.

It’s like I drag the task out just long enough to fill the available space on my calendar.

Mr Cyril Parkinson, a British historian, first explained his now-famous Parkinson’s Law in a satirical essay he wrote for The Economist in 1955. He later went on to write a book on the subject, Parkinson’s Law: The Pursuit of Progress.

Mr Parkinson had spent much of his working life in the British Civil Service, where he observed first-hand the numerous inefficiencies caused by an expanding bureaucracy.

He found that even simple tasks became more complex to fill up the time allocated to them. Conversely, as the time drew nearer for the completion of a task, it miraculously became easier to solve.

His law doesn’t just apply to time management. All needs expand when choices increase. We may be fine living in a two-bedroom apartment, but then we move to a bigger, four-bedroom apartment and find that we somehow fill the space there, too.

The French are purportedly the healthiest people in the world because they use smaller plates and thus eat smaller portions. Contrast that with filling a massive plate at an “all you can eat” buffet.

We can use Parkinson’s Law in three principal ways to become more productive:

Create constraints

When we set constraints, we simplify our life and become more efficient. Self-imposed limitations make us much more focused—and thus better at what we do.

Intentional constraints allow us to live with clarity, enjoy the things that we love, and find meaning in our actions.

A simple lifestyle, free of excessive choices, provides peace instead of chaos and creates a structure that sharpens the mind. Within this lifestyle, we become increasingly calm, creative, and proactive.

Locking myself up in a hotel with little distractions provided the constraints I needed to focus solely on my studying.

After a few days, I started to enjoy the solitude and focus that I needed, and my successful results justified all the work I had put in.

Reduce daily decisions

We make a lot of decisions—probably between 100 and 200 every day. This burdens our life with unnecessary choices, putting us under pressure and wasting energy.

From simple and mundane decisions about what to eat at breakfast, to deciding what marketing tactic to take, each option requires attention from our overactive mind.

The result? By the time noon arrives, we are exhausted and our energy has dissipated.

Reducing daily choices takes us from decision fatigue to mental clarity and sharp decision making.

When exams were approaching, I had no television, no phone, limited clothes to choose from, and a strict schedule for breakfast, lunch and dinner that repeated itself for the week I spent in the hotel. I had no decisions to make, which liberated me and helped me focus solely on studying.

Set useful deadlines

There is magic in a looming deadline. When time is short and our backs are against the wall, we often produce our best work. Emergency mode kicks in, flooding our system with adrenaline and other neurochemicals. We now focus as if our life depended on it.

On the flipside, when we have too much time to perform a task, we become lackadaisical and make a mountain out of a molehill.

The deadline I set for my study plan was effective. It was a week before the actual exams. There was no time to take it easy, I was in journalistic mode and I had to deliver per the deadline.

Parkinson’s Law teaches us to set constraints and limit choices so that we can optimise our time, focus and actions. Without buffers to slow us down and options to confuse, we are challenged to get out of our comfort zone, push harder to get things done and become more productive.

Most of all, if we apply Parkinson’s Law in these ways, we will become calmer and our heads will be clearer. Now it will be easy to make the right decision.

Opinions of Monday, 24 July 2017

Columnist: Mohammed Issa