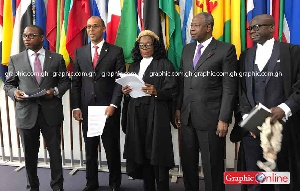

QUOTE: Ghana and Côte d'Ivoire have jointly agreed to abide by the decision of the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (ITLOS). The tribunal [had]on Saturday, September 23, 2017, unanimously held that Ghana has not violated the sovereign rights of the Ivory Coast [by carrying out] oil exploration activities [along the maritime boundary between the two countries]... At a joint press conference, the Attorney General of Ghana, Ms Gloria Afua Akuffo and the Ivory Coast's Minister of Petroleum, Energy and Development, Mr Thierry Tanoh, read out the following joint communique in English and French respectively:

“The Special Chamber of the International Tribunal of the Law of the Sea (ITLOS), constituted on 3rd December 2014 to delimit the maritime boundary between the Ivory Coast and Ghana in the Atlantic Ocean, [has] just rendered its decision this Saturday 23rd September 2017 [in Hamburg, Germany]. Our two countries... are united in the expression of our gratitude to the Special Chamber. Cote d'Ivoire and Ghana accept the decision, in accordance with the Statute of ITLOS. The Ivory Coast and Ghana seize the opportunity to reiterate the mutual commitment of the two countries to abide by the terms of this decision from the Special Chamber and to fully collaborate [on] its implementation. The two countries affirm the strong will to work together to strengthen and intensify their brotherly relationships”. UNQUOTE

When I read the words above, a song I learnt in my Presbyterian Primary School immediately came to mind. Its words, translated from Twi to English, are: “How abundantly good it is, and how beautiful it also is, that brothers should dwell together in peace!”

We used to sing this whenever we were about to engage in a competition between the school “sections” – Red, Gold, Blue and Green. The song was meant to remind us that despite the intensity of the competition, we should remain brotherly towards one another, no matter who won or lost.

Indeed, it is of spectacular significance that Ghana and the Ivory Coast have reached an amicable settlement on an issue that could not only have ruined their diplomatic relations but caused them to deploy military forces against each other. For the dispute was not just about the maritime boundary as such but the OIL AND GAS that lie in presumably large deposits beneath the waters that constitute the maritime boundary.

Ghana discovered oil and gas in commercial quantities in the disputed area in 2007. Shortly afterward, the Ivory Coast also staked a claim to portions of the area, west of Cape Three Points.

These claims were renewed in 2010, after Vanco, an oil exploration and production company operating in the Ivory Coast announced the discovery of oil in a nearby deep-water well called “Dzata-1”

It was after this discovery that the Ivory Coast petitioned the United Nations, asking for the completion of the demarcation of its maritime boundary with Ghana.

Ghana responded by setting up a “Ghana Boundary Commission”, which was charged with the responsibility of negotiating with the Ivory Coast towards finding a lasting solution to the boundary issue. However the negotiations bore no fruit, and Ghana then took the Ivory Coast to the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (ITLOS) and asked the Tribunal to adjudicate over the issue.

ITLOS’s first ruling [in 2015] placed a moratorium on new projects (exploring and/or drilling for oil], with old projects continuing. This was after the Ivory Coast had requested preliminary measures ordering Ghana to suspend all activities on the disputed area until the definitive determination of the case.

The dispute caused increasing unease in both countries, for oil can often be a dangerous trigger to political and even military hostility between neighbours.

Even within a particular country, the presence of oil in one or more regions but not in others can create tensions that threaten the unity of the country concerned. A notorious case in point is Nigeria, where (in the eyes of many commentators) the Biafran civil war of 1967-70 was caused, in large part, by the presence of oil in the areas of Nigeria that got enmeshed in the conflict.

Usually, each party in a quarrel between neighbours over oil (and in some cases, water resources) proclaims that it would abide by the decision of any international arbitration process that is set in motion to find a peaceful solution to the dispute. But quite often, such professions of faith in arbitration hide an ugly reality – each side has strong internal lobbies which desire that force should be used to impose a solution!

Here again, Nigeria provides a good example: sections of Nigerian public opinion are still opposed to the handing over, to neighbouring Cameroon by Nigeria, of the “Bakassi peninsular”, over which the two neighbours had been in dispute for quite some time. The International Court of Justice at the Hague ruled in Cameroon's favour in October 2002, but that has not cut much ice with those Nigerians who believe that Bakassi should belong to Nigeria.

Currently, areas of real or potential: conflict over borders in Africa include: the Ilemi Triangle between Sudan and Kenya; the Nadapal boundary between Kenya and South Sudan; Lake Malawi between Tanzania and Malawi; the Mingino Islands between Kenya and Uganda and the Badme territory dispute between Eritrea and Ethiopia;.

Other areas of dispute are the Island of Mbanié between Gabon and Equatorial Guinea; the frontier between Burkina Faso and Niger; as well as on the Benin–Niger frontier. In North Africa, contested territory include Moroccan claims over [Spanish territories] Ceuta and Melilla and the long-lasting Morocco and Mauritania struggle against the Polisario Front. which also affects Libya and Algeria.

In Southern Africa, Namibia and South Africa are in dispute over the Orange River; while there is also tension between Swaziland and South Africa over territory claimed by both; Namibian exploitation of the Okavango River has been a source of disagreement with Botswana; and unresolved boundaries are in dispute over portions of the Namibia, Zimbabwe and Zambia borders.

Finally, in Central Africa, there are problems concerning the boundary in the Congo River between the Republic of Congo and the DRC; Uganda and the DRC continue to claim the Kwanza Island in Lake Albert for themselves, and areas on the Semliki River with hydrocarbon potential, are capable of bringing future trouble.

In the light of all these disputes -- thankfully fairly well-contained for the moment by the African Union and the UN -- Ghana and the Ivory Coast deserve high praise for not only choosing the course of international arbitration but actually affirming – jointly – that they accept the result of the arbitration. Usually, such affirmations only pay lip service to international settlements. However, this one appears to be a real breakthrough that can serve as an example to the rest of Africa.

Let us all heave a sigh of relief, then, and hail the two countries – as was done in Hamburg on 23 September 2017. Yes, long live the brotherhood between Ghana and the Ivory Coast.

Opinions of Thursday, 28 September 2017

Columnist: Cameron Duodu