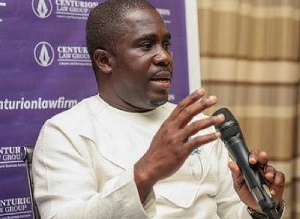

By Kwame Okoampa-Ahoofe, Jr., Ph.D.

In his brief but quite eloquent New York Times opinion piece and tribute captioned "Mandela Taught a Continent to Forgive" (12/5/13), Ghana's President John Dramani Mahama recalls a chance encounter with Africa's greatest freedom fighter and democratic leader in the twentieth century, in which the then-Minister of Communications under President Jerry John Rawlings found himself literally rooted to the spot with awe.

This is how Mr. Mahama told his story in the New York Times' opinion page: "I was relatively new to politics then, a member of Parliament and minister of communications. It was my first time in Cape Town. I had stayed out late with friends and was waiting to take the lift [or elevator] up to my hotel room. When the doors opened, there was Mandela. I took a step back and froze. As he exited, Mandela glanced in my direction and nodded. I could not return the gesture. I couldn't move, not even to [sic] blink. I just stood there in awe, thinking: here was[sic] the man for whom we had marched, sung and wept; the man from the black-and-white photograph. Here was the man who had created a new moral compass for South Africa and, as a matter of course, the entire continent."

I would extend Mr. Mahama's aptly pointed observation even further by observing that in actuality, The Madiba had created a new moral compass for the world at large. My closest encounter with this global political legend was, however, not this mesmerizing. It was not mesmerizing because in 1990, by the time that he emerged out of prison and onto the global political podium, the future of The Madiba as the first elected Black-African premier of a post-apartheid South Africa seemed to be far well into the future. And it was not even clear that it would actually come to pass.

At 76 years old in 1994, President Nelson R. Mandela would become the oldest denizen of the proverbial Cradle of Human Civilization to be democratically elected premier by the sacred tenets of the universally accepted suffrage principle of one person, one vote. The general world-wide belief was that, somehow, The Madiba would quietly and peacefully recede into the leaden twilight of history, after having successfully negotiated with the DeKlerk regime to pave the way for the presidency of a much younger Black-African citizen of that country.

Fortunately, that was not to be; having, in the quite memorable words of Mr. Mahama, "created a new moral compass for South Africa," Mr. Mandela had to logically hold up the lantern of democratic enlightenment ahead of his people into the psychological and philosophical New Canaan that was the South Africa of 1994.

Well, all in all, I had four close encounters with The Madiba in 1990, during his first post-prison tour of the United States. It was the proudest moment to be an African, regardless of one's heritage and/or nationality. This was the one moment that the hitherto sharp geographical, geopolitical and geocultural distinctions among global Africans appeared to have effectively receded into oblivion. We were now one Mega-African Family Unit, with The Madiba and his apartheid-harried - and some even claimed, apartheid-savaged - wife, the beautiful Winnie Madikizela Mandela, respectively, as the Paterfamilias and the Materfamilias.

Consistently and authoritatively, also, Mr. Mandela would demonstrate that he was not in anyway, whatsoever, beholden to the cunning and cynical operatives of any Western or Eastern superpower geopolitical entities. He would unreservedly and uninhibitedly express his profound gratitude to such incontrovertibly "reliable friends" of the Black South African cause as Cuba's President Fidel Castro and Libya's Col. Muammar-El-Gadhafy. Such effusive show of gratitude predictably staggered and flabbergasted such renowned American media heavyweights as Mr. Theodore (Ted) Koppel who, on the widely watched ABC-TV newsmagazine talking heads "Nightline," kept reminding and cautioning Mr. Mandela that he was rather recklessly and dangerously stepping on the toes of those who reserved the greatest power and influence to seriously hurt his cause and that of Black South Africans.

"Your enemies are not our enemies," The Madiba would snap at Ted Koppel and in turn remind the latter that during the nearly three decades that he spent on Robben Island and in the Pollsmoor Maximum-Security Prison doing hard labor as a prisoner-for-life, the same supposedly benevolent and generous allies of his were busy supplying the globally discredited apartheid regime with the most sophisticated of modern weaponry, to pelt and pick off the noggins of his people like bull-eye targets on a shooting range.

Mandela was completely unlike Ghana's first president, Mr. Kwame Nkrumah who, confronted on network television with White-racist segregation (or Jim Crow) in the United States, while on an official tour in 1958, or thereabouts (See Mahoney's JFK: Africa Ordeal), cynically claimed that the very existence of this most primitive and vicious violation of the human rights of African-Americans was unduly exaggerated. And here ought to be promptly recalled that Nkrumah was in search of U.S. funding for the construction of the Akosombo Dam. Mandela, on the other hand, knew how to call a spade a spade and to literally let the chips fall where they may.

___________________________________________________________

*Kwame Okoampa-Ahoofe, Jr., Ph.D.

Department of English

Nassau Community College of SUNY

Garden City, New York

Dec. 13, 2013

###

Opinions of Sunday, 5 January 2014

Columnist: Okoampa-Ahoofe, Kwame

My Madiba Moment - Part 7

Entertainment