Broken subsea cables and poor internet notwithstanding, Ghana’s social media space has been set ablaze these last few days by rumours of politically exposed persons moving large amounts of money to the United Kingdom and elsewhere, and setting off some red flags in the process.

It seems that I have found myself right in the eye of the storm by tweeting about a situation that everyone in the country’s vibrant “public affairs” community has heard being discussed in the grapevine. Even though my tweet was emphatic about the need for corroboration by trusted sources, some ruling party activists seem to think that merely by mentioning “politically exposed persons”, I am somehow putting important party-affiliated big bosses in a tight bind.

I did not tweet to provoke needless controversy. Nor was my interest in the grapevine banter merely for thrills or to sate an appetite for salacious gossip. My interest in the speculations does indeed stem from a serious policy context about politically exposed persons moving funds from Ghana overseas, not always for justifiable reasons.

The FATF Bogey

Some might recall how Ghana’s Finance Ministry celebrated when on 25th June 2021, the country was removed from the FATF grey-list, an international watchlist of countries failing in their duty to check money laundering and terrorism financing.

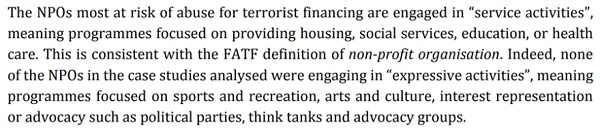

Ghana was placed on that list in 2019 because of failures to address, among others, recommendation 8 of the FATF checklist, which deals with how a jurisdiction regulates services-delivering Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) and the risk they can pose as conduits for shady money. The NGOs being referred here are those that offer social services like health, education and economic development, rather than those classed as “expressive” (such as think tanks or advocacy institutions).

To quote from the relevant FATF document:

Note: “NPOs” = “Non-Profit Organisations” (also known as, Non-Governmental Organisations)

Upon showing substantial progress during site visits in 2016 and 2018 by GIABA, an ECOWAS-affiliated body that conducts FATF audits in West Africa, Ghana was declared “partially compliant” with Recommendation 8, largely compliant with several other recommendations, and was subsequently removed from the grey-list. Another site visit was scheduled for May 2023, but no information is publicly available about the country’s latest performance on the FATF scorecard.

This is not the full account of Ghana’s FATF story, anyway.

The Politically Exposed

On 22nd June 2012, Ghana was first placed on the FATF grey list. GIABA’s initial assessment in 2009 had shown extensive failings in managing the risks of Anti-Money Laundering/Counter-Terrorism Financing (AML/CTF) as a jurisdiction. One of the country’s principal weaknesses was in the area of managing the risks posed by Politically Exposed Persons (PEPs).

The FATF system draws on Article 52 of the UN Convention Against Corruption (UNCAC) to define PEPs as:

“Individuals who are or have been entrusted with prominent public functions both in [Ghana] or in foreign countries and people or entities associated with them. PEPs also include person who are or have been trusted with a prominent functions by international organization.”

PEPs include:

i. Heads of State or government; ii. Ministers of State; iii. Politicians; iv. High ranking political party officials; and v. An artificial politically exposed person (an unnatural legal entity. belonging to a PEP); vi. Senior public officials; vii. Senior Judicial officials viii. Senior military officials; ix. Chief executives of state owned companies/corporations; x. Family members or close associates of PEPs. xi. Traditional Rulers

Because such powerful individuals easily find fronts for their nefarious activities, the term is also officially understood to cover their “relatives and close associates”.

When in February 2012, Ghana was first placed on the FATF list, as one of just 12 countries in the world to receive this dubious honour, very little by way of policies, laws, and guidelines had been put in place to regulate the risks that PEPs pose to governance of the country’s financial system. Some of the key gaps identified in the original 2009 GIABA site visit were as follows:

Securities, insurance and stock exchange regulated entities are not subject to requirements to assess the political status of their clients.

Requirements to put additional risk management systems in place to determine whether a potential customer or a customer or the beneficial owner of a customer is PEP.

There is no requirement to obtain senior management approval prior to opening an account for a PEP;

No sectors are subject to a requirement to obtain senior management approval to continue a relationship when an existing customer is discovered to have been or to have become PEP.

Insurance, Securities and Stock Exchange regulated firms are not subject to a requirement to establish the source of funds of a PEP;

No sectors are subject to a requirement to conduct enhanced due diligence should they decide to provide services to a PEP.

A 2010 follow-up report said that these problems still persisted. Following the grey-listing action in 2012, Ghana began taking steps to correct this, eventually leading to the country’s removal from the FATF grey-list on 22nd February 2013.

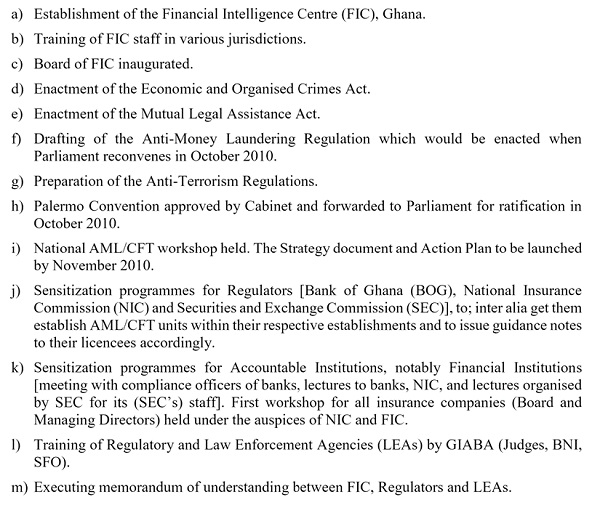

By 2017, the FATF was reporting progress made in developing a bunch of regulations and policies to tackle the risks posed by PEPs, as well as other critical shortcomings identified in the 2009 initial site visit. A list of some of the actions taken by Ghana to impress the GIABA FATF auditors is below.

If the reader has been paying attention so far, he would have noticed that 6 years later, on 22nd February 2019, the country was back on the list. Since, these international ratings are dynamic, Ghana could find itself back on the list should the authorities slack in complying with the spirit and letter of the 40 recommendations.

At the time that I posted the tweet, I was in the middle of reviewing a number of critical shortcomings in Ghana’s PEP management regime. I had been having conversations with a variety of people. It is in that light that when someone passed information from compliance professionals in the UK suggesting that Ghanaian PEPs have been flagged in the UK and that in some instances their transactions have been defended on the grounds of Ghanaian government interest and/or national security, I started to take the grapevine speculation more seriously.

Because our work involves the cultivation of sources, it is sometimes necessary to alert the public about ongoing work, even at an early stage, so that other “whistleblowers” and “tippers” will be motivated to get in touch. In the circumstances, this difficult, careful, and skill-intensive work continues unabated, but we are under no illusions that we can obtain results easily or overnight. We persist because we must.

Ghana’s broken Politically Exposed Persons (PEPs) financial Risk Management System

Since posting that tweet, I have noticed a serious lack of understanding of the basic facts of AML/CFT and cross-border financial controls.

Some commentary assume that all suspected AML/CFT incidents automatically lead to criminal action or law enforcement investigations. Whilst others mistakenly assume that every PEP-related cash transfer incident must automatically be dealt with by law enforcement agencies as a matter of suspected crime. Problematic PEP-related AML/CFT activity however span a wide spectrum, and many are dealt with at the level of the financial institutions involved.

In my ongoing review, I have noticed that the Ghanaian authorities have made massive, commendable, improvement on the ECOWAS-managed FATF assessments in the last ten years (with periodic slippages, such as in 2018 – 2020) by creating a plethora of policies, guidelines, and new institutions. Actual compliance with certain key recommendations, particularly the ones dealing with PEPs (such as recommendations 12 and 22), however, remains severely lacking.

For example, the Bank of Ghana – Financial intelligence Center guidelines on the subject (December 2022) for instance requires as follows:

“Financial institutions shall take reasonable measures to establish the source of wealth and the sources of funds of customers and beneficial-owners identified as PEPs and report all anomalies immediately to the FIC and other relevant authorities.”

FATF’s expectations of compliance with such measures rest on this assumption:

“Many countries with asset disclosure systems have provisions in place on public access to the information in the disclosures, and make disclosures available on-line. While in many cases only a summary of the information filed by officials is made publicly available, the information that can be accessed sometimes includes categories such as values of income, real estate, stock holdings sources of income, positions on boards of companies, etcetera. Often, financial institutions and DNFBPs must primarily rely on a declaration by the (potential) customer.”

The truth is that in Ghana, this arrangement is a bit of a charade. The asset disclosure regime is widely regarded as ineffective. It is neither transparent nor easy to draw upon to hold any PEP accountable for their wealth.

The exhortations to financial institutions such as the one immediately following are thus quite naïve.

“If the PEP‟s net worth has grown substantially in a short amount of time, do you have a clear explanation for the sudden growth? Check source of wealth and source of funds.”

Every Ghanaian knows many PEPs who have become wealthy overnight and freely utilises the financial system without any hard questions being asked of them by anyone. The requirement that all transactions by PEPs should be reported to the Financial Intelligence Center (FIC) is also widely known to be regularly flouted because the mechanisms for identifying “relatives and close associates” are lax and poorly maintained.

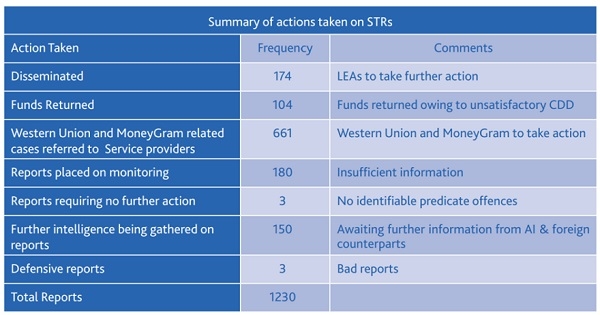

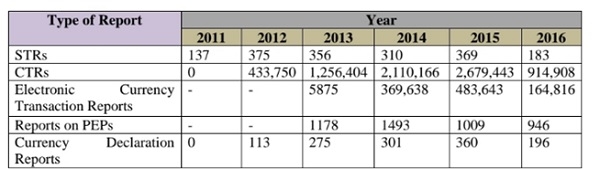

The FIC itself has not published its annual reports for nearly 5 years now, in contravention of the hallowed transparency regime of the FATF. But in its last publicly available report, issued in 2019, there is nothing whatsoever to show that even Suspicious Transaction Reports (the highest-risk category for reporting) relating to PEPs are receiving priority attention.

No information is provided whatsoever about any investigations involving PEPs, creating the impression as if all has been calm on the front. But that is far from the reality. In fact, despite expert opinion that things have been worsening, the volume of Suspicious Transactions Reports actually fell consistently until Ghana was shoved back onto the FATF grey-list again in 2019.

This is NOT just some theory

The whole country was seriously embarrassed when it was revealed that Ghana International Bank (GIB), a Bank of Ghana owned entity based in London, was seriously lax in enforcing standard anti-money laundering provisions involving its corresponding banking partners, most of whom are Ghanaian banks. GIB was fined nearly £6 million for these infractions by the UK’s Financial Conduct Authority (FCA), and only because it essentially “pled guilty” and was thus graced with a discount. Virtually none of these AML infractions became the subject of law enforcement action in the UK, but that does not mean that they were not grave.

A few years before GIB’s fine, evidence came to light in an employment tribunal hearing that a PEP had flown to London with his suitcases stuffed with nearly £200,000 and a further ~$200,000. The PEP had no trouble getting a senior GIB banker to pick up the cash, deposit some in his London account, and transfer the rest to FCA. This matter did not attract an FCA sanction, much less the attention of the UK law enforcement authorities. Yet, the GIB banker was fired for AML-related misconduct.

The point here being that Ghanaian PEP abuse of AML safeguards is rampant but most incidents remain under the radar of regulatory and law enforcement, both in Ghana and the UK, because they are dealt with by Bank Compliance officials, who then submit such information in routine reports. The sheer volume of such reports make it highly unlikely that every such incident will attract formal law enforcement investigations and penalties.

Even when the authorities are involved in investigating a PEP-related AML incident, poor transparency and arbitrary decision-making makes it quite difficult to understand the motivations behind enforcement.

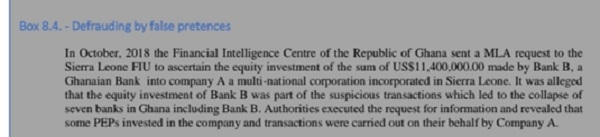

Take this case recorded by GIABA:

The identity of this PEP that shipped $11.4 million to Sierra Leone was never disclosed. No public prosecution records can be found on the incident. Nobody has accounted about anything to anyone. Had GIABA not captured it, it would have remained only in the grapevine. But even GIABA does not dare name names without the sanction of the authorities.

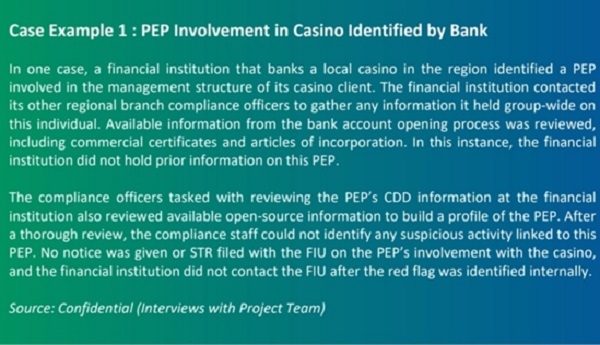

Similar reports of how PEPs have discovered the sports-betting and casino industries sprouting up all over the region as ripe for their money carting activities occasionally show up in GIABA monitoring, corroborating widespread grapevine speculation. But little actual transparent law enforcement activity occurs in response.

As western governments succumb to industry pressure to loosen strict AML rules, source countries like Ghana for AML and PEP-related money flows into Europe will certainly intensify. The problem is that our economies will suffer for it. And the resulting laxity will create more conditions for Ghana to return to the grey-list.

Fighting PEP Financial Abuses is challenging but critical

The reader might consider all this grey-list business esoteric compared to the much more obvious harm of monies being sucked out of economies like Ghana which are desperate for cash to address basic problems like electricity generation and distribution. But the truth is that FATF grey-listing does matter. IMF studies have shown that grey-listing can shave as much as 7.6% off GDP, curtail foreign direct investment by an average of 3% and crash other inbound investment flows by up to 3.6% of GDP.

Ghanaians may be justifiably impatient about uncovering PEPs involved in suspicious financial transactions, and even bringing them to book. But it is important to recognise the intricate complexity of these matters, especially the cultivation of sources and the fightback of powerful individuals, and to realise that concerted, and consistent, work by many of us is, and will be, required to effectively bring issues to light and address the risks posed to Ghana’s economic well-being by PEP financial misconduct. And, of course, we must always bear in mind that a PEP can’t be judged guilty simply because he or she is a PEP.

Opinions of Thursday, 21 March 2024

Columnist: Bright Simons