Prof. Kofi Kissi Dompere notes in his book “The Theory of Philosophical Consciencism” (p. 319):

“In general, philosophical consciencism must be constructed with the use of epistemic tools of that society as well as the experiential information structure of the society. The epistemic tools and the experiential information structure may be internally constructed or externally induced.”

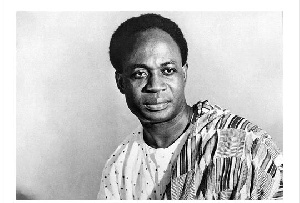

This remarkable statement clearly defines the task of restructuring African societies to fit the categorical expectations of what one of the world’s and Africa’s most important and foremost philosophers and political strategists, Kwame Nkrumah called “philosophical consciencism” in the policy domains of socio-economic and socio-political development.

This important question of economic development remained a central feature of Nkrumah’s ideational and pragmatic reformulating of Africa’s economic and political geography to meet the analytic rigors of his formulaic, strategic epistemology of philosophical consciencism, a social-economic-political vision fortified by an enabling infrastructure of humanism, equity, and social justice.

Nevertheless, it is a nagging question that required the advanced instruments of mathematics, science, and logic to unravel its subterranean complexities in order that the potential of Africa can finally be unleashed to address the myriad material and spiritual needs of its industrious people.

Yet the question has neither been seriously, confidently posed nor sufficiently addressed, if at all, by the post-Nkrumah leadership of Africa, a leadership mostly made up of uninformed and misguided characters with Eurocentric and neocolonial casts of mind. A number of observers have noted that this leadership with a prosthetic, borrowed head does not have the strategic interests of Africa at heart, the reason Africa continues to bleed internally, let alone divest itself of its Eurocentric pretexts and inveterate hatred for Africa. These African leaders are the real enemies of Africa.

It is, however, within reason to advance the argument that the epistemic implications of this progressive intellectual vison which Prof. Dompere thoughtfully sets up for African intellectuals, researchers, academics, and policy makers to digest, ideally calls for serious, firm, and African-centered adjudication in the corridors of the academy and of power, given its potential and largely unexplored benefits in the unconsidered arenas of pragmatic nationalism and comparative advantage.

This is all the more important because the question itself, an indispensable one at that, carries an unresolved continuum of Diopian imperativeness into contemporary discourse on development, political economy, and pertinent issues of national prioritization. A case can be made that African leaders, researchers, policy makers, and academics have consistently failed to reach a rallying consensus on this important question of development economics on account of their Eurocentric orientation. Perhaps, Nkrumah was among the very few who provided the most forceful arguments charting the way forward for Africa out of its externally imposed developmental quagmire.

We should quickly add that what Noam Chomsky calls “manufacturing consent” may partly explain the Machiavellian proclivities of this African Eurocentric leadership in preventing a critical mass from among the masses rising up against the entrenched decay. What Prof. Dompere calls ‘an awakened intelligentsia” to challenge the status quo seems to be in perpetual hibernation, and whether this awakened intelligentsia, a silent minority, can usefully translate itself into the kind of critical mass required to bring about the expected African-centered revolution in thought and action among the masses remains to be seen. Before then, the dilemma however remains unresolved.

But then again the conscious distortion of Africa, in addition to the phenomena of manufacturing consent and agitprop and social engineering, in international affairs and relations has an underlying economic motive, mostly, a policy statement that, for all intents and purposes, may or may not have anything to do with the corollary question of economic imperative and economic justice. It is nonetheless a complex question that demands thoughtful, uncompromising, educated response from African intellectuals and academics.

Now talking about the conscious distortion of Africa, in the controversial book “The South African Gandhi,” for instance, South African scholars Desai and Vahed, both of Indian descent, provide powerful insights into certain convenient economic arrangements calculated to support the status quo and to reinforce relations of unequal dichotomy between the major races. They write (p. 102):

“The tax challenged patriarchal authority in Zulu society, which was incrementally destroyed by the British from the 1880s, and ‘disrupted the spiritual forces that linked sons to their fathers and their fathers’ fathers whose shades watched over the homestead.’”

They note elsewhere (p. 106):

“Competitive challenges for the colonial market from independent African producers brought antagonism from white settlers long before the assault on the Indian trader and was dealt with through a variety of state-sponsored methods, particularly various forms of taxation that had the effect of forcing many Africans into the labour market.”

What are they saying? Propaganda churned out from official and non-official state sources in the racist South African political economy turned hardworking South African blacks into a leprosarium farmhouse of ungrateful, undignified loafers, a mischievous characterization that led to outrageous taxes being forcibly imposed on them to support and underwrite the expensive lifestyle of White South Africa.

Even Mahatma Gandhi, who lived in South Africa for some 21 years and practiced law there, a place where he also developed his controversial profile of activist persona and nonviolent resistance, meekly succumbed to this outrageously convenient labeling of South African blacks as lazy for his own selfish ends, wondering what he would have made of the destruction of Black Wall Street via the Tulsa Race Riot (1921). In this regard, Desai and Vahed write of Gandhi (p. 107):

“…the statements on African laziness and inferiority make Gandhi stand out not as one of apartheid’s first opponents but as one of its first proponents.”

All these statements and observations do not take into consideration the industrious personality of the African and how this quality spawned a captivating panorama of cultural and historical richness across the length and breadth of pre-colonial Africa, where the African state, classical African civilizations and empires matched their counterparts elsewhere on the planet, including the advanced civilizations of pre-Columbian America, China, Greece, and Rome to mention but three.

In fact, pre-colonial African civilizations served as templates for the Greco-Roman worlds. Cheikh Anta Diop’s meticulous arguments set forth in “African Origin of Civilization” and “Pre-colonial Black Africa,” and those discursively advanced by America’s first urban sociologist and prolific academic, African-American scholar W.E.B. Du Bois’ “The World and Africa,” as well as by Molefi Kete Asante’s “History of Africa,” and Thomas Brophy’s and Robert Bauval’s “Black Genesis: The Prehistoric Origins of Ancient Egypt,” all eloquently speak to this contentious academic and scientific question on the primacy of classical African civilizations and humanity in carrying the rest of the world along the paths of intellectual and cultural development.

Ultimately, it is not in question also that Africa is indubitably the autochthonous home of mankind, Africa’s empowering humanity quintessentially having been the creative embodiment and source of the phenomenology of the soul and spirit of man.

None of these, however, imputes any imposing typology of superior humanity to Africans. In this case we emphasize that Africans are equal in intellection and mental capacity to other humans. The history of human intellectual development confirms this fact. And this important history remains inviolate or sacrosanct today, although history is sometimes written to favor and protect the privileges, interests, and supremacy of one group over the other (s). Prof. James W. Loewen’s “Lies My Teacher Told Me: Everything Your American Textbook Got Wrong,” “Lies Across America: What Our Historic Sites Got Wrong,” “Lies My Teacher Told Me About Christopher Columbus: What Your History Books Got Wrong” are a special case in point.

Granted the above, what differences there actually might in fact be could be merely reduced to serious questions of culture and of cultural exegesis, or of interpretation of the environment, and even of perception in the humanistic topology of race relations. Racism and ethnic chauvinism therefore tend to dissemble our common humanity, thereby undermining the oversight of collective efforts and solidarity in the face of the grinding challenges posed by the human condition.

Du Bois was indeed not far from incorrect when he prophetically asserted in “The Souls of Black Folk” that “the problem of the 20th century is the color-line.” We should bear in mind that the concept of “race” itself has no biological or scientific basis in fact, although one cannot deny its entrenched element of sociological import and political signification in intra- and inter-national psychosocialization and academic discourse. We are here referring specifically to the political sociology of “race.”

If so, then what becomes of the seemingly perennial question that Africans are inferior? This question resolves into a roaring cascade of related queries, of which the justification for slavery, the Transatlantic Slave Trade, so-called, became a rallying anthem for slavers and their sympathizers, a form of moral anesthesia marshalled against the specter of universal guilt associated with the undignified commodification of African humanity. It was possible then to strip the African of any semblance of civilization. Thus slavery and colonization seared the conscience of the perpetrators, which made it possible for them to manufacture alibis for their own moral lapses and gross misdeeds. Bob Marley may have captured this for us on the track “Guiltiness”:

“Guiltiness

“Pressed on their conscience

“And they live their lives

“On false pretense every day, each and every day…

“They'll eat the bread of sorrow….

As Shakespeare had Antony say in “Julius Caesar,” “The evil men do lives after them…” The real motivation for slavery and its corollary, colonization, it would turn out, was an economic one, though this one too was carefully dressed in a deceptive rhetoric of civilizing mission, reportedly meant to bring native Africans out of their caged Neanderthal cottage of primitive rawness and savagery.

That slavery and colonization were ultimately good for the pagan African. “Asiento” eventually entered the picture.

No one told the enslaved African that capital and land, two crucial factors of production were readily available to the colonizers, except for labor, which Africans would have to supply to meet acute labor shortage in colonial America and elsewhere across the Western Hemisphere.

Therein lies the still-unresolved policy conundrum posed by Africa’s continuing underdevelopment, a concept which Walter Rodney’s “How Europe Underdeveloped Africa” painstakingly articulates in surgical precision. In other words, denigrating the humanity of Africa corrupted the political morality of what should otherwise have constituted a just economic imperative, though not necessarily for a commercial undertaking as morally egregious and outrageous as slavery and colonization.

The alleged inferiority of Africans can therefore be traced to this concocted justification for the Transatlantic Slave Trade, which also became a rallying anthem for the eventual colonization of the continent of Africa and its welcoming humanity. The postcolonial writer and novelist, Ngugi wa Thiong’o’s “Something Torn and New” painstakingly details the planned calculus leading to the colonization of Africa. According to Thiong’o, the British used similar strategies to colonize the Irish.

We should stress that before the Euro-Christian enslavement of Africans, and colonization of Africa, Arabs and Muslims had been the main traders in human flesh. The Muslim-Arab world, like its Euro-Christian counterpart, imposed its cultural hegemony on Africa. This led to gross distortions in the African cultural character as they could not have succeeded enslaving and colonizing Africa without first questioning Africans’ humanity and degrading their cultural and historical accomplishments.

The African was consequently reduced to an animal, forcibly made the humanoid sibling of primates in thought, action, body, and intellect. This set the stage for scientific racism, or that scientific racism gave birth to the animalization of the African, the Chicken-or-the Egg question, whatever, in the space of political socialization.

This distorted perception of the African has continued almost unabated in Western literature (see Joseph Conrad’s famous or infamous novel “Heart of Darkness,” for instance) and mass media, Hollywood movies, the political discourse of right-wing personalities and conservatives, and the world of white supremacist groups. Our friend Milton Allimadi’s book “The Hearts of Darkness” sharply critiques Western journalism on Africa. American journalism Professor Neil Henry’ “American Carnival: Journalism under Seige in an Age of New Media” critiques American journalism, exposing how the media unfairly treat minorities particularly African Americans.

Other important matters

The mass media in Africa, on the other hand, are not doing any better. For instance, investigative journalism in Africa is far from the critical pole of ideological neutrality and political partisanship. In fact, non-partisan investigative journalists are an endangered species in Africa, while the African mass media themselves behave as though they are bastardized copycat appendages to those of the metropoles, aping the uncritical journalese and singing the praises of the metropoles, and refusing to act as the moral voice and conscience of the masses.

Then having lost the critical eye and rigors of African-centered methodology and critiquing of African societies, including of the external patrons of Africa's kleptocrats, the African media have instead chosen to become infected prostitutes in bed with the continent's Eurocentric leadership. The African media have simply taken on the fawning characterology of Malcolm X’s proverbial house slave. Regardless, Bob Marley captures a dimension of this contradictory nature of historical revisionism and media distortions on the track “Crazy Baldhead”:

“I'n'I build a cabin

“I'n'I plant the corn

“Didn't my people before me

“Slave for this country?

“Now you look me with that scorn

“Then you eat up all my corn…

“Build your penitentiary, we build your schools

“Brainwash education to make us the fools

“Hate is your reward for our love

“Telling us of your God above

Unfortunately, the Eurocentric leadership across Africa is trapped in a cesspool of cognitive imbecility, rendering it incapable of negating these entrenched warped perceptions. Self-trust, victorious consciousness, and possibility thinking are priceless currencies we need to cultivate for our own collective survival given that, after all, the myriad problems we are confronted with are not idiopathic to say the least. Africa needs to invest in its own internal resources and not get trapped in the embrace of Ellisonian invisibility. Diop’s “Black Africa: The Economic and Cultural Basis for a Federated State” provides some of the most creative answers to our developmental conundrums.

This is where Nkrumah’s reformist ideas on philosophical consciencism and categorial conversion come into the bigger picture. Nkrumah formulated these creative ideas to help negotiate Africa out of the overlapping contradictions brought about by the forced grafting of Euro-Christian culture/Arabo-Muslim culture and ideas onto African culture, including inducing self-hatred in the vast majority of Africans. The African in this condition supports and underwrites his own negation through self-destruction, self-hatred, and hatred for nation-building.

In these related contexts, Nobel Laureate Wole Soyinka’s “Of Africa” is intellectually and factually revealing when it comes to the question of the internecine tensions that have accrued, and continues to accrue, between the purported cosmopolitan humanism of Traditional African Religion on one hand and the invasive hegemony of Islam and Christianity on the other hand, and the dire implications of these tensions for political stability and development across the continent.

What then is philosophical consciencism? Prof. Dompere defines it thusly (p. 326):

“The set of propositions within which a philosophy in support of an African liberating ideology retains Africentric humanism and collective freedom…”

He continues (p. 327):

“The epistemic totality of philosophical consciencism is a structure of cognitive program for knowledge production and use, logic of institutional creation, strategic social-policy formulation and creative-destructive positive-action process to continually set the potential against the actual in the dynamics of social systemicity.

“In this respect, philosophical consciencism is the backbone of socio-economic transformation actions in the actual-potential polarity where the transformation actions are social decision-choice dependent.

“It is this interdependency between philosophical consciencism and social decision-choice system with relational continuum and unity that allows one to claim that national social history is an enveloping of success-failure outcomes of decision-information process.”

Prof. Dompere is calling for a revolution in thought and action. This goes all the way to curriculum development. It appears, then, that the problem we have on our hands may be essentially a battle of ideas. The West, quite frankly unlike Africa, understands the power of information and intelligence and how to effectively use them to serve it ends, to control the world and its strategic interests for purposes of economic advantage, while the neocolonial African leadership of today merely exists as a fawning appendage to this most sophisticated of imperialistic matrix and design.

The ideological conflict from which Africa is expected to redeem itself, to restructure its priorities to serve its people and to develop the continent, to recapture its lost sense of self and degraded humanity, to exert its influence and moral authority on the character of global politics, and to reinstate humanism and confidence and the African personality in politics simply boils down to mediating the polarizing questions of “oppressive intentionality” and “liberation intentionality” (Dompere, p. 328).

Africa is at a critical crossroads as regards this matter, and it is also ironically where its future lies. In the main, whether Prof. Dompere’s ideas point to the question of essentialism is irrelevant here. What is rather important here is that, as Profs. Asante and Dompere have consistently argued, the solutions to African problems are within Africa itself and that it is incumbent upon Africans to come together in the spirit of oneness and for the unquestioned love of and loyalty to the continent to find these solutions, a view Bob Marley shares on the song “Zimbabwe”:

“No more internal power struggle

“We come together to overcome the little trouble…

“'Cause I don't want my people to be contrary…

“To divide and rule could only tear us apart

“In everyman chest, there beats a heart…

“And I don't want my people to be tricked by mercenaries…

“Every man got a right to decide his own destiny

Yes, we have every right to decide our destiny without the calculating intrusiveness of external interests.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

“According to last month’s edition of ‘African Business’ magazine, the total mineral wealth of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) is estimated to be $24 trillion – equivalent to the GDP of Europe and the United States combined.

“The DRC has the world’s largest reserves of cobalt and significant quantities of the world’s diamonds, gold and copper. This makes the DRC potentially the richest country in the world.

“But this central African country has been ranked among the poorest and most underdeveloped countries on this planet…” (Rasna Warah)

African leaders and scholars who lack African-centered academic training tend to forget that the art of dehumanizing an entire race or ethnic group directly and indirectly translates into undue economic advantage for whichever group that manages to successfully control and own the powerful language of economic relations on the international stage. Negating this misanthropic tendency and bringing the shine of cosmopolitan humanism to bear on race relations, globalization, human development, and modern civilization are the greatest challenges we face today.

Information ownership is power itself, which then feeds the engine of power dynamics as it relates to economic relations. Again, this salient fact is lost entirely on the African leadership. Knowledge deficit about Africa in the international community, and also about the continent's potential to make a positive change in human affairs, is patently undermined by the lingering specter of information asymmetry in favor of those who control and manage the traffic of global information. Nkrumah realized this and put in place institutional mechanisms to address the anomaly. As Bob Marley said on the track "One Love":

“One love

"One heart...

"Let's get together and feel alright...

"Let's get together and fight this holy Armageddon...

What Bob Marley called "holy Armageddon" is an albatross around our neck, a Sisyphean problem requiring radical resolution. The challenging, painful paradox of the Congolese example as set forth in the epigraph cautions us against turning our backs on the grand vision of Nkrumah. At this point we should say both Prof. Dompere and Nkrumah have spoken well for the African world, and this is highly commendable. In the next essay we shall explore other dimensions of the former’s ideas and the role which Black Studies and researchers and academics in the field have to play in reversing and challenging the distortions in the African personality. Africology is Africa’s future, no doubt.

That said, readers may as well consult Prof. Dompere’s body of scientific works and those of Nkrumah.

Opinions of Wednesday, 27 December 2017

Columnist: Francis Kwarteng