Introduction

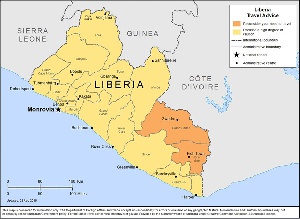

Liberia is a country situated on the shores of the North Atlantic Ocean in West Africa. It is covering a landmark of about 43,000 sq. miles and has a population of about 4.98 Million, its capital city is Monrovia, which has a population of over 1.01 million (Chapter 4, n.d; Worldometers, 2019).

In contrast to most African countries, Liberia was never authoritatively colonized; it became a Republic in 1847, having been founded by slaves who had been returned to the African continent from the US subsequent to being sans set (Chapter 4, n.d). Liberia, in this way, respects the United States of America as its pseudo-colonialist.

There are 16 indigenous clans in Liberia with the dominant one being the Kpelle, representing about 20% of the population (Chapter 4, n.d). There are additional descendants of freed slaves who landed in Liberia after 1820, who make up under 5% of the population (US Department of State, 2010).

The official language of Liberia is English. The country is Christian-dominated, with overwhelmingly (85%) of the country’s population, while Muslims make up 12% of the country’s population (US Department of State, 2010). Although the country is a Christian dominated nation, socio-cultural practices in the form of secret societies are integral in the lives of most segments of the population. Such secret social orders exist in both the Americo-Liberian and indigenous socio-cultural groups (Chapter 4, n.d). The two most generally recognized indigenous secret social orders are the Sande (for ladies) and Poro (for men). These social orders, found within the society include the Vai, Gola, Dei, Mende, Gbandi, Loma and Kpelle, portrayed as organizations to culturally assimilate youth and formally bring them through the soul changing experience from kid to adulthood.

Poro and Sande are the most generally known, in light of the fact that they are the least complicated and demanding. Regularly, all grown-up individuals from a network are called for initiation. Other progressively undercover social orders, with furtive enrollment, committed to correspondence with specific kinds of profound powers also exist. Americo-Liberians carried with them mystery enrollment foundations, for example, the Freemasons.

For a long time, Liberia was among the peaceful and stable nations in Africa until the beginning of the civil war, which disrupted the nation’s growth and brought it onto its knees. The country is still struggling to recuperate from the years of civil conflicts and the effects of devastating war. The political changes taking place are aimed at sustaining the peace and maintaining stability for economic growth and prosperity.

In November 2005, the country started a new path of democratic rule with the election of Mrs. Ellen Johnson Sirleaf as President of the Republic. Her success at the polls made her the pioneer African woman to be Head of State and Government (Chapter 4, n.d).

Liberia has witnessed scores of anti-government protests over the years in various forms and at different stages. And, unless the unexpected happens, which I wish happens, there could be another one dubbed “Save the State” which is scheduled to take place on June 7, 2019. However, it appears that the government is determined to ensure that the opposition discontinues its “peaceful protests.” This paper begins by providing a brief history of war and conflict in Liberia, discusses protests in the country, and advances the way forward to the ongoing public defiance and murmuring in the country. It should be noted that, whether protests or demonstrations, however peaceful, must aim at preserving the peace and stability of the state.

The History of Conflicts in Liberia

The free-born American blacks and freed slaves also called Americo-Liberians had established Liberia in the 1820s and led the country since independence in 1847. The Americo-Liberians for a long time, in this manner, controlled the Republic. They ran the new nation like a state, setting up a primitive governance structure with all social, economic, and political controls in their hands. They marginalized the natives who despite dominating the settlers (Americo-Liberians) by twenty to one in ratio, were exposed to an influx of maltreatment, including constraint from working, disappointment, and rejection from the very beginning all of which resulted to their impoverishment and social distance, while the decision class thrived (see Chapter 4, n.d).

By the 1970s however, this once unassailable power structure started hinting at disintegrating into another faction of displeased, foreign-trained Liberians. This was in the form of schools of indigenous technocrats, united in different resistance gatherings, who started voicing their requests for change (Momodu, 2016). Their frustrations reached the limit in 1979 with the "rice revolts," a 2000-in number challenge, started due to a 50 percent increase in the price of rice, the nation’s staple food. This incident started as a peaceful protest went into pandemonium when police forcefully disrupted the group, maimed, and killed more than 50 protestors and injured over 500 others (Momodu, 2016). The protest coupled with other underlining discontentment led to the 1980 military overthrow that brought Master Sergeant Samuel Kanyon Doe, an ethnic Krahn from Grand Gedeh, to power as the first native head of state in the history of the country.

At first, the military coup initially enjoyed the support of the Liberian people because the military would correct the deep-rooted ills of society occasioned by the horrendous, dehumanizing conditions imposed by the Americo-Liberians rule dating from the founding of the nation state. But, over time, majority of the people felt disappointed in the government, as it failed to run an all-inclusive government, mismanagement of the country and instead, aggravated the problems (see Momodu, 2016).

The subsequent years were characterized by mounting agitation, due to an inexorable ethnic-inspired dictatorial routine. This advanced the joint militarization, ethnically based legislative discourse, and ruled over a sinking economy, occasioned by social-economic decline and hardship among the population (see Insight on conflict, 2010; Momodu, 2016). Against this backdrop, other ethnic coteries started plotting their own ascent to control, coming full circle in 1985 with a ruthlessly smothered attempted overthrow led by Thomas Quiwonkpa, an ethnic Gio from Nimba County.

This attempted coup led to the killing of several Krahns and selective arrests of ethnic Krahn government officials and individuals with close ties to the Doe regime. Following the murder of Quiwonkpa, Doe's warriors, predominantly Krahn elements of the Armed Forces of Liberia (AFL) started a battle of reprisal killings, targeted at Gios and Manos, a closely related people from Nimba County (See Momodu, 2016).

In the course of the last three decades, Liberians are still hopeful for an end to war-like situations and economic hardship. The contention started in December of 1989 when revolutionary minded Charles Taylor, a former Doe supporter, attacked Nimba County from neighboring Ivory Coast. The Taylor led-rebels called themselves the National Patriotic Front of Liberia (NPFL). The AFL in defense of the state engaged the group in counter-insurgency battle, resulting in the loss of precious lives and destruction of properties. Overtime and unabatedly, the NPFL swelled in number and gained more territories by exploiting the Gios and Manos. The majority of these rebels were young men and women stranded amid the rushes of reprisal killings or just rankled by the assaults against their innocent kin by the AFL. Concurrently, the NPFL was leading its very own rule of terror on innocent citizens and allies of the Doe regime, primarily the Krahns, and the Mandingos. By 1990, the rebels had taken control of major towns and cities across the country except for Monrovia, the capital city of Liberia (See Insight on conflict, 2010; Momodu, 2016).

What followed was an excruciating seven years of tribal war. By the later part of 1990, the NPFL fragment group, the Independent National Patriotic Front (INFL), which caught, tortured and executed President Doe, had achieved its pinnacle and blurred (see Momodu, 2016). In any case, the United Liberation Movement for Democracy (ULIMO), formed by Liberian exiles in Sierra Leone and Guinea who had been loyal to President Doe, were making gains from over the fringe into southwestern Liberia. In 1993, the Liberia Peace Council (LPC), comprising predominantly Krahns believed to be elements of the AFL, waged war on the NPFL and took control of the East and Southeastern parts of Liberia (see Momodu, 2016).

From 1989-1997, there were various fizzled endeavors to bring the nation into harmony, especially efforts led by ECOWAS and the rest of the international community. However, the bloody ethnic conflicts and the brutal killings of innocent Liberians defined these eight years of nation wreckage. A large number of Liberian men, women, children, and elderly were murdered and others subjected to torture, assault, and rape (see Insight on conflict, 2010; Momodu, 2016). Although the contention was established in authentic complaints extending back over 100 years, the ethnicity inspired nature of the civil conflicts and wars orchestrated by the violence rebellion started by Taylor's NPFL, with the involvement of the AFL, and later ULIMO and others were beforehand alien to the Liberian way of life and history. At last, in 1997, a truce was reached, and before long, Mr. Charles Taylor, the previous Warlord of the NPFL, was chosen the leader of the nation (Insight on conflict, 2010; Momodu, 2017).

Distastefully, the Taylor government was characterized by debasement and abuse of power, further heightening divisions, and sense of social exclusion, aversion, and hate, which already existed as debris from the ethnically propelled conflicts (Momodu, 2017). State influence was consistently utilized for the individual enhancement of government authorities with practically zero responsibility to the Liberian populace (Momodu, 2017).

Then came the LURD insurgency from the borders with Guinea, which started in 2000, was the fifth genuine flare-up of brutality in Liberia since Taylor's decision and propelled Liberia once more into four additional long years of constant fighting (Insight on conflict, 2010; Momodu, 2017). In August 2003, an arranged truce, the flight of Charles Taylor from office and the nation, and the intervention of regional and later universal peacekeepers ended significant clashes thus charting a new path that then ushered Liberia into a dispensation of democratic governance (see Insight on conflict, 2010; Momodu, 2017).

A review of peaceful protests in Africa

There has been a wide range of dissent leading to protestations within the Africa region and around the world. According to Gray (2019), given the shallow likeness of such occasions to one another notably the sensational pictures of masses of individuals in the lanes starting with one area then onto the next, starting with one state then onto the next is a characterizing trademark. The spike in challenges on the African mainland is turning into a unique pattern in global governmental issues (Gray, 2019).

A few challenges have neglected to interpret dissent dynamism into feasible establishment building or political contestation; others have prompted the formation of new ideological groups or economic effect in states where the marvel happened (Gray, 2019). Challenges have flared in numerous nations recording relatively high rates of financial development and political headway, yet financial inconveniences have been the issue here and there, however typically less important than political ones.

In latest, resistances and civil society developments were effective to compel some long-serving African heads of state and tyrants to be constrained from office (Gray, 2019). The rundown of nations that have been hit by significant dissents since 2010 to present is astoundingly long, including Tunisia, Libya, Sudan, Burkina Faso, Guinea, Algeria, Burundi, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, among others (Gray, 2019). In context, a great number of rebellions and anti-government protests has occurred in Africa.

The quantum of anti-establishment protests in North Africa and the Middle East has vacillated more than any other region, with the most sensational one being that of the Arab Spring, which started in December 2010 through to 2011, and latest dissents in Sudan and Algeria. Large numbers of these conflicts have been significant occasions in the nations where they have occurred. They are regularly enormous scale social occasions of natives who are resolved to challenge the status quo and the entire establishment. Protestors are always at hand to defy maltreatment or brutality by security forces, which more often acted in support of the government in such instances (Gray, 2019), but this often comes at a high price at the expense of the protesters.

It gives the idea that political factors additionally show to have been the fundamental drivers of latest dissents crosswise over Africa, particularly in Algeria, Libya, Sudan, Burkina Faso, Guinea and other semi tyrant settings. In various cases, explicit political issues fill-in as triggers, bringing out nonconformists who are furious about unworkable strategy and awful administration; economic issues seem to have assumed just an auxiliary job in a considerable lot of these cases, aside from in the political settings (Gray, 2019). The rise of citizen’s dissents has in some instances compelled governments to make knee-jerk reactions, which are not sustainable, leading to subsequent or future challenges.

The Impending June 7 Protest

Liberia's recent past must remind us to explore an amicable approach to settle the mounting social, economic and political challenges, such that Liberians and foreign nationals can live peacefully without the echoes of gunfire and other dangerous weapons, or without the nation being divided between factional lines. A careful review of the ongoing political scuffles reveals that the opposition and the government appear inflexible to accelerate dialogue to address the prevailing circumstances faced by the country.

This situation characterizes some of the same elements that escalated previous crises, which led to full-blown civil wars that destroyed the country. It is therefore essential that organizers and patrons of the planned “June 7” protest should consider the country's monstrous and blood-driven darkest past calmly. Looking for a peaceful way to reach a win-win compromise, should be the overarching interest of all actors. It is not enough to only be patriotic, but also show patriotism in every aspect, even in time of excruciating disagreements, particularly regarding situations that have the potential to disrupt public peace and security and, therefore, undermine the very survival of the suffering masses whose interest is being advocated.

As of now, the masterminds for the June 7, 2019 demonstration are beating their chests about their natural and unavoidably authorized ideal to stand up, to gather and to put out their complaints to their legislators and other elected officials. From different media outlets, it is believed that the masterminds are fighting rather militantly that nothing can obstruct their entitlement to challenge and their entitlement to amass in open spots. As indicated by some through their publications and utterances, Liberia is misgoverned; everything is self-destructing, as confirm by across the board hardship and monetary loss of motion and that they would not sit detached without carrying their disputes to the legislature and the world community through civil means as guaranteed by the Constitution of Liberia.

Then again, Government and its supporters are depicting the planned demonstrations as unfavorable, unnecessary, and disruptive planned by disappointed political opponents to give false impressions about the condition of things in the country and by this to score political gains. In defense, government spokespersons have been unanimous in their argument that the government is in dire financial crises inherited from the previous UP-led government. Those opposed to the protest maintain that the planned demonstration in itself is evil and unpatriotic in nature and an attempt to send wrong signals to the international community that Liberia is unstable and, therefore, unfit for business.

There is no denying the fact that protest or demonstration is a powerful tool when peaceful to communicate dissent and to hold government accountable to its mandate. It is healthy, for every government to entertain constructive criticisms and accept oppositions who act as a watchdog. It allows the government to understand the grievances and the feelings of its citizens and begin to look for ways to address them. Accordingly, Gray (2019) posited that President Weah's administration has a social obligation to engage in dialogue with organizers of the June 7 protest to find common ground regarding unfolding challenging developments at the home front.

From a personal perspective, dialogue is encouraged and would be significant to address issues at best within the framework of national cohesion. At the same time, peaceful protest that is well-coordinated with meaningful consultations with elected officials and protection secured from the state is equally important because, through that, citizens would raise crucial grievances.

Practical Steps to Prevent Conflicts Taking cognizance of the fact that democracy is the government of the people for the people and by the people, implies that both the government and the opposition are accountable to the people. All state actors must recognize that the concept of a social contract in general terms means that people give up some of their rights to some form of authority – a government in exchange for a stable social order, to assure political, social, and economic stability and inclusiveness.

This is necessary in the interest of lasting peace and security for the state and greater good of the people. Aligning with many other well-meaning individuals, including Mr. Josephus Moses Gray, President George Weah’s administration and organizers of the June 7 protest must continue to dialogue, which is the surest way of exploring the roots of the many crises that we face today. It enables inquiry into, and understanding of, the sorts of processes that fragment and interfere with real communication. Practical steps necessary to avoid a peaceful protest degenerating into conflict in Liberia: 1. The Government should continue to grant audience to the organizers of the June 7 “Save the State” Protest and should not be perceived as enemies, but as partners from the other divide, with the aim of steering our dear Country to an enviable rank.

2. Through their selected representatives, the protest organizers should present their case in a concise and precise manner, identifying the root causes of such protest to address the underlining issues amicably. By so doing, the nation takes advantage of the opportunity to realign national policies and priorities.

3. The Government should set up a National Peace Council, a body of distinguished citizens, not limited to religious and traditional leaders, to help in dialogues of this nature. This institution has made significant gains in other countries and it is time Liberia considers such initiatives in solving national issues.

4. The Legislators, as representatives of the people should step up to engage with their constituencies to regularly bring to the forefront their grievances and concerns to central administration, to avoid a likelihood of regular citizens reverting to a state of despair, agitation or protests.

5. It is worthy of note, that the President of the Republic is not, by himself, the government. There are three branches of government, and all such institutions must take responsibility of the state of the nation and also work around the clock for the resolution of same.

6. The protest organizers should exercise caution not to dwell on the problems only but collaborate for possible solutions that will accelerate the country out of the critical situations and improve the quality of life of ordinary citizens.

Let us all take cognizance of the provisions of our Constitution which provides in Article 15 that “Every person shall have the right to freedom of expression, being fully responsible for the abuse thereof. This right shall not be curtailed, restricted or enjoined by government save during an emergency declared in accordance with this Constitution.”

And Article 17 that “All persons, at all times, in an orderly and peaceable manner, shall have the right to assemble and consult upon the common good, to instruct their representatives, to petition the Government or other functionaries for the redress of grievances and to associate fully with others or refuse to associate in political parties, trade unions and other organizations”.

Conclusion

For the greater good of our country, it behooves both government and organizers of the planned "June 7 protest" to strive towards preserving a peaceful climate. Strengthening peace will require both conflict-sensitive implementation of durable solutions. Government and other state actors should address factors that could breed conflict, and continually heal this nation that is deeply damaged from the scourge of prolonged conflicts and war.

Peace-building in Liberia embodies a vision of a society that is peaceful, respects and protects the rights of citizens and ensures that disputes and tensions which are typical to any society are handled in ways that prevent their escalation into organized violence.

I hope that all, the government, political party leaders, civil society organizations and other key state actors, will take concrete steps that will lead us all towards inclusive engagements for the greater good of our beloved country now and for the future!

References

Chapter 4. (n.d). Background on Liberia and the Conflict. Retrieved from https://www.theadvocatesforhumanrights.org/uploads/chapter_4-background_on_liberia_and_the_conflict.pdf

Gray, J. M. (2019). Is There Any Cause to Protest On June 7 in Liberia? An Assessment of the Impacts and Consequences of Protests Around Africa. Front Page Africa. Retrieved from https://frontpageafricaonline.com/opinion/commentary/is-there-any-cause-to-protest-on-june-7-in-liberia-an-assessment-of-the-impacts-and-consequences-of-protests-around-africa/

Insight on conflict (2010). Conflict Profile: Liberia. Retrieved from http://www.insightonconflict.org/conflicts/liberia/conflict-profile/ Momodu, S. (2016). First Liberian Civil War (1989 – 1996). Blackpast. Retrieved from https://www.blackpast.org/global-african-history/first-liberian-civil-war-1989-1996/ Momodu, S. (2017). Second Liberian Civil War (1999 – 2002). Blackpast. Retrieved from https://www.blackpast.org/global-african-history/second-liberian-civil-war-1999-2003/ US Department of State (2010). Background Note: Liberia. Retrieved from http://www.state.gov/r/pa/ei/bgn/6618.htm.

Worldometers (2019). Liberia Population (live). UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, Retrieved from https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/liberia-population/

Disclaimer This publication is written in my capacity as a citizen of the Republic of Liberia and a scholar. This publication, therefore, does not reflect the opinion or has any bearing on the organizations/institutions with which I work.

Opinions of Monday, 3 June 2019

Columnist: William Deiyan Towah, Ph.D

Preserve the peace and stability of the Liberian state

Entertainment