During my doctoral program, we went on a field trip to Mali. We visited a mosque, where we observed a prayer session. It was during this period that members of this Muslim group gathered to pray and worship at a mosque that a sheikh managed. For hours, thousands of young people sat on the floor, chatting about prayer and Quranic verses, shaking and twisting their heads as if they were having fits. They repeatedly prayed and chanted Quranic verses in ways that grew into a crescendo, then they would suddenly stop.

The leading imam would preach for a while, and off they went again. After some hours, they broke to eat and later returned to continue the prayer and preaching session. This process went on for weeks. While observing the session, I wondered how this way of praying would impact the minds of these youths and others across the region.

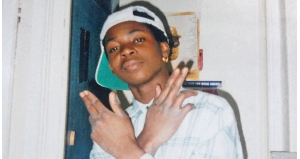

Programmed to blindly believe, some of these youth end up fanatical or radical Muslims. They constitute a part of the mob that violently responds to supposed insults to the prophet of Islam, the desecration of the Islamic holy book, and other manifestations of extremism in different parts of Africa and the world. They engage in violent reactions to alleged blasphemy or apostasy. For instance, on February 1, the media in Nigeria reported the case of a Christian man, Habu. He was accused of blasphemy after he made a post on Facebook questioning the foundation of Islam and the origins of the Quran. The man went into hiding after his car and house were set ablaze. Some Muslim students beat to death a Christian colleague, Deborah Samuel after they accused her of making a post on the student WhatsApp platform that insulted the prophet of Islam. A Nigerian humanist, Mubarak Bala, remains in jail for allegedly making a post on Facebook that was considered critical of the same prophet.

African youths often participate in witch-hunting campaigns. They blindly and dogmatically believe in witches, sanction, instigate, and commission witch and demon hunting and exorcism in their families and communities. Young people constitute the lynch mob, the stoners of alleged witches, and the executors of jungle justice against the accused in communities. At public squares, children are seen watching and cheering the torture and murder of alleged witches. Some of these children grow up to become witch hunters.

For decades, I have been campaigning to end witch-hunting and other superstition-based abuses. I have been working to defend victims of blasphemy allegations and ensure allegers are brought to justice. I have pondered how to foster a more critical-thinking society free from these horrific abuses.

There has been a consensus on the importance of critical thinking for social change and progress. However, not much effort has been devoted to developing and delivering resources to schools. Little has been done to turn the critical thinking rhetoric into action. The real challenge has been how to foster these mental habits in schools and societies, especially in African schools where English, French, Portuguese, Spanish, and other colonial languages are the languages of instruction. Pupils and students speak these languages as their second or third language. At early stages, these languages require learning because there is an overemphasis on the language, not the content of instruction, on memorization of received wisdom, or on a critical evaluation of what is taught or learned.

In response to this problem, I researched and noticed that the inculcation of critical and reflective thinking is enshrined in the national policy on education as one of the goals of primary education in Nigeria. But there is no subject focused on fostering critical thinking skills in elementary schools. Primary schools offered verbal and quantitative reasoning as subjects. So there was a lack of materials or resources to deliver the subject of critical thinking to schools. To deliver the subject, there must be books, texts, and other materials.

During the lockdown, I set out to develop some critical thinking learning materials for primary schoolers. I tailored the text to suit Nigerian pupils who speak English as a second language. Children and other young learners in Africa find themselves in a unique schooling circumstance and situation that we gloss over to our peril. Critical thinking lessons should be articulated to address the economic, cultural, political, and social needs of students. At elementary schools, many children rote-learn in languages other than their mother tongue and grow up thinking that power and authority lie in memorization. They grow up blindly and dogmatically believing. Children are brought up to think that education is mainly about getting jobs, and they travel overseas most often to do menial jobs. They are socialized not to have their own opinions and not to question what they are told or taught by their parents or teachers. Children are brought up not to question foreign religious teachings and sacred texts. Child education is parent-centered, teacher-centered, priest-centered, or imam-centered.

So, I tried to operationalize critical thinking so that it could be taught in elementary schools so that it could be infused or embedded in other subjects and hopefully improve the quality of teaching and learning. I explored various definitions of critical thinking. Most definitions stress the ability to analyze, synthesize, and evaluate information, ideas, and experiences. Of course, these are fantastic definitions. However, I was interested in a definition that could be operationalized and materialized at the elementary school level for children who speak English as a second language. I wanted the subject of critical thinking to be presented and delivered in a way that primary school children would find entertaining, in a way that would make critical thinking fun.

I adopted the definition of critical thinking as asking probing questions like "How do you know?", Why should I trust you? Is it true? etc. I found the definition measurable, suitable, and accessible to elementary schoolers. Critical reasoning becomes the ability to generate questions in all areas of human endeavor. Critical thinking is question-storming. Lessons are created to test and enhance the capacity of children to challenge and interrogate ideas and issues. At elementary school, children are taught to question whatever they see, hear, touch, or smell. Various formats and approaches are being developed to foster critical thinking skills. They include a question-to-question, a question-to-answer, and a question-to-command approach.

As operationalized, critical thinking will help realize a paradigm shift in the culture of teaching and learning in schools. Learning has mainly been teacher-centered. Teachers are often seen as the embodiments of knowledge and understanding. Education is a teacher-to-student process. Teachers are seen as the main dispensers of wisdom and lead generators of questions. But with the teaching of critical thinking, the power relationship will change. Learning will be inquiry-based because teachers are stimulators, not generators of questions. The generation of questions, not answers and solutions, is the test of knowledge and intelligence. Asking questions for the question's sake, not for the answer's sake, becomes a mechanism in the school and learning process.

In addition, critical thinking has some pedagogical value. It can contribute to the science of child education. A questionstorm is a way of teaching and delivering lessons. In this case, children learn through questioning. They gain information and understanding through the interrogation of objects and texts presented to them. Teaching is done by responding to questions that students generate. Teachers supply information and answers that learners are further subject to interrogation. Teaching and learning are participatory, student-led, or child- or learner-centered. Learning becomes a rolling wheel of interrogation and information, question and answer, problem and solution, criticism, and clarification.

So far, the first edition of Primaries 1 to 3 texts and other learning aid materials have been produced to address the critical thinking needs of students. Other critical thinking resources, like charts, are being developed. The program has a website where these materials are displayed. The site is still a work in progress. The texts and charts have been used to organize workshops for pupils and teachers in selected schools. So far, over two thousand teachers and three thousand students have participated in the workshop. At the moment, the Critical Thinking Social Empowerment Foundation is taking care of the costs of producing the texts and running the workshops for teachers and in schools. We rely on donations and sponsorships to produce educational materials and organize workshops in schools.

In recent months, we have been corresponding with affiliates of philosophy for children in other parts of the world on how to connect our programs with other efforts to foster critical reasoning and intellectual exploration by and for children. We plan to organize critical thinking competitions where children and schools will contest and win prizes for excellence in questioning and interrogation. We also plan to encourage schools to establish thought laboratories and set aside a building or an apartment for more intense critical reasoning exercises.

To sustain this program, we need the support of all who value inquiry-based learning. We need opportunities to draw attention to the significance of critical thinking in education and learning in African schools. We need agencies to partner with us in promoting the program and in the production and distribution of resources and materials. We need fellowships and scholarships for our researchers and trainers. We need funding to organize our workshops and pilot programs in schools, especially in public and poorly funded schools, because these schools are recruiting and breeding grounds for witch hunters and religious fanatics.

In an increasingly globalized world, critical thinking in Africa is imperative to the realization of peace and progress. Many wars and conflicts in the region are often linked to a lack of critical thinking, such as those linked to religion and other superstitions. Stagnation and underdevelopment are connected to a dearth of critical reasoning and inquiry. The inculcation of critical thinking skills will help improve the quality of education and learning. It will unleash the intellectual potential and possibilities of Africans and help position Africans for 21st-century jobs. Critical thinking will help Africans to be productive and to meaningfully navigate life in an information-driven age. More importantly, critical thinking will awaken Africans from the slumber occasioned by unreason and the dark and destructive influence of witch-hunting and religious extremism.

Opinions of Tuesday, 19 March 2024

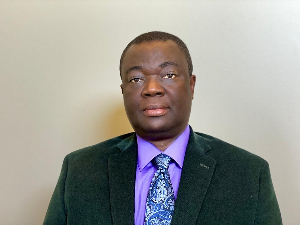

Columnist: Leo Igwe

Questionstorm: Why critical thinking matters in Africa

Entertainment

Amakye Dede to mark 50 years anniversary with world tour

Opinions