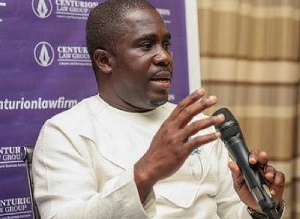

By Kwame Okoampa-Ahoofe, Jr., Ph.D.

Mr. K. B. Asante is quite right in observing that the annual celebration of Republic Day as a national holiday in Ghana has lost its significance on our national calendar (See “‘Republic Day Has Lost Its Significance’ – K. B. Asante” JoyOnline.com/Ghanaweb.com 7/1/12). Indeed, I would even venture further in demanding that the Republic Day holiday festivities be revoked and immediately replaced by the annual commemoration of the Rawlings-Tsikata-engineered brutal assassination of the three Ghanaian High Court Judges and the retired Ghana Army Officer on June 30, 1982. Of course, I am not the first Ghanaian citizen and/or political commentator to make this suggestion.

Interestingly, though, I vehemently disagree with Mr. Asante, a former secretary to the late President Kwame Nkrumah, that the latter’s proclamation of Ghana, in 1960, as a “Republic” had anything remotely to do with Nkrumah’s desperate bid to establishing the newly-independent erstwhile Gold Coast as a “self-reliant” polity. Nothing could be farther from the truth.

To be certain, the largely rigged 1960 presidential election was deviously and mischievously geared towards making Nkrumah and his so-called Convention People’s Party (CPP) regime far less accountable to the people than the two entities had ever been since 1951, when Nkrumah was electorally swept into office as Leader of Government Business and shortly, thereafter, as the transitional Prime Minister of the former British colony of the Gold Coast (See Dennis Austin’s Politics in Ghana: 1946-1960). Hitherto, as pertained to the British or Westminster system of governance, Prime Minister Nkrumah had been obligated to report the activities of his administration to the Ghanaian Parliament on a weekly basis. Unfortunately, as the CPP cabal of unconscionable thuggocrats found itself deeply engulfed in shocking incidents of corruption and the thieving of our national coffers, as well as the wasteful spending by the Prime Minister on his obsessive pan-Africanist ambitions and other ventures sardonically characterized by his most ardent political opponents and detractors as “prestige projects,” Busia preferred to characterize some of these ventures as “titivating” or decorative projects devoid of substance, Nkrumah found it increasingly difficult to defend the credibility of his CPP government regularly and periodically before the sworn representatives of the Ghanaian people. Between 1954 and 1961, for example, at least two major scandals had struck the CPP, one of which had been investigated by the celebrated Jibowu Commission. Thus, even if Ghana’s declaration as a Republic, by then-Prime Minister Nkrumah, had been even remotely about self-reliance, as the self-interested Mr. K. B. Asante would have Ghanaians who do not know any better assume, the future President Nkrumah would have regularly continued to report the activities of his government to a Parliament which, by the way, was also heavily dominated by members of his own Convention People’s Party, even in the absence of the neocolonialist representative of the Queen of England, the Governor-General. Instead, the Life-Chairman of the CPP shamelessly rubberstamped himself into some weird phenomenon called an “Executive President” and, almost overnight, became a virtual law unto himself. He would, henceforth, leisurely sit in his commodious office at the Flagstaff House or Independence Square and single-handedly and single-mindedly draft laws at whim and have his parliamentary “yes-men” and women ratify them without their ever being subjected to any thoughtful and/or meaningful debate on the floor of the House (See Austin’s Politics in Ghana).

Sad to observe, but it clearly appears to me that this shameful travesty is what Mr. K. B. Asante finds acute delight in characterizing as Nkrumah’s heroic push for self-reliance. In reality, what Nkrumah’s rather egomaniacal declaration of Ghana as a Republic in 1960 succeeded in doing was to make the civilized world, largely the Western countries, and even his Eastern-bloc friends and allies, envisage Ghanaians as a bunch of clinical cretins blindly tied to the coattails of an arrogant dictator who almost equated himself with one of the three doctrinal elements of the Trinitarian ideology of Christian theology. And like Germany’s Chancellor Adolf Hitler before him, Nkrumah and his henchmen of pathological kleptocrats would sacrilegiously and psychologically indoctrinate impressionable Ghanaian youths into envisaging their increasingly self-absorbed leader as an immortal. The youthful captives of the notorious Young Pioneer Movement (YPM) would be thoroughly brainwashed into thoughtlessly chanting such scientifically erratic slogans as “Nkrumah Never Dies!” “Nkrumah Is God!” and “Nkrumah Carries Africa On His Head With An Egg-Made Pad.”

Needless to say, Ghanaians were far smarter than their egomaniacal leader preferred to credit them for, as shall shortly be revealed by the thunderous approbation and the legion anti-Nkrumah musical compositions that greeted the Show Boy’s overthrow by the Kotoka-led National Liberation Council (NLC) on February 24, 1966. Ironically, in the 1960 presidential election, in which Nkrumah claimed to have won more than 90-percent of all legitimate ballots cast, far less than 50-percent of the eligible voters had actually gone into the polling booth (See Austin’s Politics in Ghana: 1946-1960). Predictably, the latter political charade would be followed by massive imprisonments, tortures and downright assassinations of the most ardent opponents of Ghana’s newly-elected Executive President.

Conversely, what makes the celebration of June 30 as a national holiday imperative is the immediate, and sharp, awareness that this barbaric event brought home to both Ghanaians and the international community at large, regarding the largely flimsy and illusive veneer that veritably is the much-touted mantra of Ghana as a placid and staid polity inhabited by mild-mannered and peace-loving people. It would also, refreshingly and admirably, showcase the country’s savagely victimized Akan majority to be incontrovertibly ranked among the most temperamentally tolerant and emotionally and psychologically enlightened sub-nationality of humans on Earth. June 30 would also rudely awaken Ghanaians to the delicate balance in which our collective sense of a cohesive national identity hung. June 30, therefore, more closely reflects the desires and aspirations of Ghanaians for a salutary state of tolerance and magnanimity in the face of hideous savagery and a threatened state of bestial chaos and anomie.

*Kwame Okoampa-Ahoofe, Jr., Ph.D., is Associate Professor of English, Journalism and Creative Writing at Nassau Community College of the State University of New York, Garden City. He is Director of The Sintim-Aboagye Center for Politics and Culture and author of “Ghanaian Politics Today” (Lulu.com, 2008). E-mail: okoampaahoofe@optimum.net. ###

Opinions of Tuesday, 3 July 2012

Columnist: Okoampa-Ahoofe, Kwame

Republic Day Blindly Celebrates Nkrumah’s Reign-of-Terror

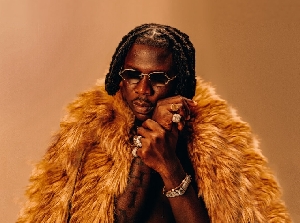

Entertainment