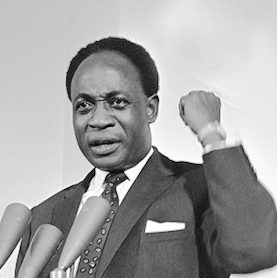

When Osagyefo Dr. Kwame Nkrumah inaugurated the Tema Motorway in November 1965, he declared it to be the first of many such motorways he planned for Ghana. What the Osagyefo didn’t say, however, was the personal toll this project exacted on him; from fights with his own cabinet to confrontation with the same evil forces who bombed him at Kulungugu.

The Tema motorway project added fodder to claims that Osagyefo was indeed a ‘dictator’ who listened to no one when his mind was made up about something.

As Ghana marked its 64th Republic Day on Monday, what you’re about to read is the story of the conception of the Tema Motorway, as was told to me by the late K.B. Asante in his home when I used to pay him regular visits.

When Nkrumah decided to build the Tema Motorway, he originally wanted a dual four-lane motorway modeled after a similar one he saw in Europe during a foreign trip.

I don’t know about our leaders today, but back then, Nkrumah was known for observing and noting down the "good things" other countries implemented during his travels. Most times, when Nkrumah returned from a foreign trip and summoned a minister, it was likely about some idea he'd “imported” and wanted to discuss. In some way, Nkrumah was indeed a "dictator,” so far as the ideas he wanted to

implement were concerned. Brilliant, workable ideas animated him, but his ministers usually had doubts.

However, if he had listened to them, there would have been no Akosombo Dam or the many technical and vocational training schools he built because they always advised gradualism. Of course, not all the ideas Nkrumah had were foolproof.

Not to digress, but for context, the Preventive Detention Act (PDA) was a presumably fine idea he “imported” from abroad. Facing post-independence violence and tribal unrest in Ghana, Nkrumah drew inspiration from fellow ex-British colony India's successful 1950 preventive detention law, instituted by Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, who also contended with secessionist threats and communal violence in his newly independent country.

So the Tema motorway idea came to Nkrumah from abroad. Many reports cite the Autobahn in Germany as Nkrumah’s inspiration. The Osagyefo summoned Dowuona Hammond, his Minister of Transport and Communication, to discuss his plan to link Accra to Tema using a four-lane per-side motorway.

After a back and forth, it was clear the money for the motorway was not ‘sitting there’. Ghana had just finished the Akosombo Dam at great cost. The Job 600 project was also under construction at a significant expense. Cocoa prices had fallen. Swollen shoots have affected cocoa yields. Labor was demanding wage increase.

Nkrumah’s Minister did not support the idea.

“GBP3.4million just to link Accra and the Tema village?” He asked. At the time, Tema was indeed a village with vast lands stretching all the way from present-day Nungua to Dawhenya. One minister told K.B. Asante, “Apart from the harbor and Coca-Cola, what at all is in Tema?”

Nkrumah was told the project was a waste of money. But undeterred, Nkrumah said he would present the idea before his cabinet. Before the cabinet meeting, several ministers approached K.B. Asante, urging him to persuade “your man” to abandon the project. They argued that it would be an economic disaster.

According to K.B. Asante, he timed Nkrumah and found him in a good mood to approach him with the issue.

But Nkrumah angrily retorted in Twi: “Fior”, pointing at the door, meaning “go away”. The cabinet meeting eventually took place. They discussed various issues until the topic of the motorway project came up. Everyone remained silent.

It was alleged that the ministers had discussed the tension in the country privately and agreed to unanimously advise that the project be postponed. Nkrumah looked around the table, exchanging glances with each other, but no one spoke.

Everybody kept quiet. He waited. No one spoke. 3 minutes…. Silence… Then Nkrumah started.

He acknowledged there were difficulties but said they were temporary. He explained why the motorway project and the Akosombo Dam he just finished were key to the future of Ghana he wanted to build.

He explained his vision of Tema as West Africa’s industrial city, serving our landlocked neighbours’ import and manufacturing needs. He said he wanted a four-lane iron-rod reinforced concrete with an asphaltic overlay on each side—so eight lanes in all for heavy-duty vehicles that will ply the road to and from this Tema industry, he foresaw.

The room remained silent. Everyone knew the country's financial situation was tight, but Nkrumah, anticipating this concern, insisted forcefully that the government find the money to build the motorway.

Then K.B. Asante cleared his throat, breaking the tense silence. He was the first to speak. K.B. praised Nkrumah for his vision, acknowledging the ambition behind the motorway project. "I actually agree with you, Osagyefo," he began, "but..." Nkrumah was listening and looking at the faces around the room.

K.B. Asante suggested a single-track road, even if the motorway must be built at all. Almost everyone in the meeting started murmuring in agreement with him.

One after the other, they all argued for a single lane to Tema. They said in 10 or 15 years, another lane may be added if the times call for it. And indeed, measured against the facts of the day, they were right. But Nkrumah was looking far ahead of them.

Their arguments were sound: Ghana was short on money, and at the time, less than 5000 people worked in Tema. It was a growing industrial hub that didn’t look like it could pay for the 3 million pounds about to be invested on its roads, despite the fact that the harbor competed there 2 years ago, in 1962. Nkrumah listened to them all make their case one after the other while playing with his pen and writing down sketches. All of them took turns explaining why it was too expensive and/or not prudent to use scarce money.

After listening to all their arguments, Nkrumah spoke. He declared that he wanted the record to show that he acknowledged their concerns but chose not to heed them. However, he was willing to make a concession since it was the ministers who would communicate and defend the project to the public.

He proposed reducing the highway to two lanes instead of four.

Nkrumah was furious when one minister said the 19-kilometer road should be done in phases spread over 5 or 10 years. Nkrumah refused.

Despite the continued lack of agreement, Nkrumah asserted his authority, reminding them that it was his vision that Ghanaians had voted for, not theirs. He claimed he could see in his eyes what Tema would become in a “few years before our very eyes.”.

Nkrumah said he foresaw heavy vehicular traffic building between Tema and Accra when his dream of transforming Tema into the industrial hub of the newly independent Ghana began to materialize, hence the need for the project as soon as practicable.

I must state that Nkrumah did not anticipate Tema becoming a vast residential area with communities numbering from 1 to—what is it now—25 or 30. Yet, imagine Ghana today without the Tema Motorway.

As a final note, Nkrumah had discussed with Arthur Lewis (his technical policy advisor) some modalities where the project could pay for itself, including placing a toll at entry and exit points of the motorway.

Now the problem was convincing the whole nation to accept it!

This was a nation facing tough times.

There have been occasional shortages of essentials like bread, sugar, milk, and sardines.

In those days, if you received your salary on the 28th of the month, by the time you reached the market, those paid on the 25th would have already bought up all the essentials.

Nkrumah was striving to address these shortages, but with limited success.

To add insult to injury, the motorway project came at a time when other significant expenditures by Nkrumah, like the Job 600 project, were being criticized—and indeed justifiably—as wasteful and irrelevant prestige projects under the guise of “visionary undertakings.”

So there was understandable skepticism around the project.

Who sets the flame? Guess? The National Liberation Movement (NLM)!

“There goes our tin-god dictator again!” They fired the first shot.

They condemned the project as a dictator’s useless pet project. They incited labour.

According to the NLM, the money Nkrumah wanted to use for the Tema Motorway project should have been used to provide the basic necessities of life for Ghanaians.

Ghanaian labour unions, although largely pro-CPP, nevertheless showed open opposition to the Tema Motorway project.

They went on strike for over a week, demanding one thing: Nkrumah must drop the Tema Motorway project entirely.

In fact, earlier, the same unions protested for two weeks against the building of the Akosombo Dam, saying it should be postponed as the nation was not ready then. They said it was a waste of resources.

In responding to the protests and criticisms, Nkrumah told the nation that those projects they always criticized as useless were not mere feats of engineering for his ego but symbols of a new nation's aspirations and that those projects would shape the future of Ghana he wanted to build.

Now, it is safe to say that I am writing this from within the future Nkrumah foresaw and sought to build. I have seen the future Nkrumah saw nearly 60 years ago. The Tema Motorway, the Akosombo Dam, and the Harbour, among other ambitious projects he pushed, were not merely about meeting immediate needs or satisfying an ego but rather about setting a course for long-term national development for Ghana.

Nkrumah’s leadership persona is characterized by a visionary outlook that has left an indelible mark on Ghana's progress.

While Nkrumah was not perfect—evidence of which is littered in this story—his intentions and vision for the future of Ghana remain unparalleled. Judging our leaders by their foresight and ambition, I dare ask: Is there anyone like him?

As we mark Republic Day, navigating the complexities that have become our modern Ghana, it is essential, in my opinion, to remember the value of forward-thinking leadership if we must build the Ghana we all want. It is not merely about winning an election; it is about driving transformational change through the intentional pursuit of nation-building through visionary leadership that sees into the future what ordinary citizens cannot see.

On the occasion of Republic Day, Nkrumah's legacy shows us the way; it teaches us, if we care to pay attention, that true progress most times requires bold decisions and a willingness to face opposition with conviction and sincere intentions.

As we continue to build our nation, we must seek leaders who, like Nkrumah, can envision a brighter future and take decisive, even unpopular steps to make it—that future they envision—a reality for all, not just a few.

On the occasion of our Republic Day, Nkrumah's contributions stand tall as a benchmark for the aspirations and actions of all who strive to lead Ghana into its next chapter, whether as presidents or vice presidents.

God bless our homeland, Ghana. And Long Live Nkrumah.

Opinions of Wednesday, 3 July 2024

Columnist: Mikdad Mohammed