It is not easy to be a woman writer in Africa. (I might just as well say that it is not easy to be a writer in Africa –male or female!)

But the point is that whatever the difficulties that face a writer in Africa, they are doubly, if not triply, experienced by an African writer who is also a woman.

Generally speaking, the modern African writer is supposed to be 'cautious' in choosing what to write about. No serious social criticism should be attempted, it is assumed.

Why? Because that might “give ammunition” to those who want to denigrate Africa to continue exploiting or oppressing her.

No “politics” (it is also assumed).

Why? Because although people like Graham Greene, Ernest Hemingway or George Orwell (to say nothing of E M Forster, whose Aspects of the Novel is often cited as a rule book for would-be novelists) permitted themselves to write about anything that came to their minds, African writers should be careful not to “tread on the toes” of important people in the political or commercial fields, be they Africans or non-Africans.

Such taboos face all African writers, but it appears that those that subconsciously apply to African women writers are more insidious. The poor ladies are expected -- by societies steeped in moral hypocrisy -- to be “modest” enough not to write about whether they enjoy sex or not.

Nor to express strong opinions about men’s cruelty to women (if any comes to their notice.)

Why? Otherwise, men would “be scared” of marrying them! If they condemned oafish behaviour in other women, it could be taken for “jealousy”.

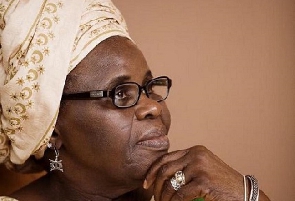

Ama Ata Aidoo, [our DEAR SISTER who has just died aged 81] was one African woman writer who made her own rules and couldn’t care less whether what she said or wrote pleased other people or not, be they, men or women.

Let me give readers one example: at a public discussion held in her honour at the London Library, she was being fawned upon by many African women in the audience. One of them asked her (as a way of indirectly acknowledging how “special” she herself was!) what she thought about the scarcity of young African women writers.

“Have you tried to read them?” Ama shot back. “They are all over the place! Just Google!”

An uneasy outbreak of tittering greeted this response.

Typical Ama. “For God’s sake, do the basic things first before you come to waste people’s time,“ she implied. And one shivered on behalf of the many "lazy" students who had passed through her hands during her career as a teacher and Professor.

Ama was “larger than life (and in relation to her, the phrase is not an exaggeration.) Built by nature with the luxuriant flesh and openness of the African woman who had no apologies to make about her so-called “figure”, be she at the chief’s palace or the marketplace, she complemented her naturalness with the sharp tongue of someone who KNEW what words were actually about.

In the years of her intellectual formation, she moved in the company of fellow writers (like the “earthy” Kofi Awoonor) who practically made the English language sound like their backyard patois. I regret that in the company of such "smart" linguistic craftsmen, I once used crude language whilst talking to Ama.

But Not only did she NOT mind, but she also replied in kind! Now, that’s what I call a liberated African woman!

It was whilst acquiring her secondary school education at the famous Wesley Girls’ High School (“Wegehe”) in Cape Coast, that she was prescient enough, when asked by a favourite teacher of hers, Ms Bowman, what she wanted to be when she grew up, to tell her that she wanted to be a “Poet”!

“Poet”? The astonished teacher asked. “But Christine (Ama’s Christian name) Poets do not bring food to the table!”

However, this same teacher was so perceptive as to give Ama a typewriter as a gift, at a later date!

She didn't use it to become a shorthand typist! I am sure that as her writing career flourished after school and she made money out of the plays, novels and poems she published, Ama hit the keys of that typewriter with special relish, as she said in her mind to the said teacher: “No food to the table, eh? Take that!”

Ama was born on 23 March 1942 at Abeadzi (near Saltpond) in the Central Region.

Her self-confidence was implanted in her at an early age, for she was the daughter of Nana Yaw Fama, the chief of Abeadzi. Her mother was Maame Abasema.

Ama’s political attitude was underpinned by the fact that her grandfather was murdered by the British colonial administration. This brutal fact brought to her father's attention, the absolute importance of educating the children and families of the village on the history and events of the era. Thus, it was he who built the first school in the village and made sure that Ama attended it.

Ama arrived at Wesley Girls in 1957, the year of Ghana’s independence. After that, she went to the University of Ghana, Legon, where she read English. It was while she was a student at Legon that she wrote her first play, The Dilemma Of A Ghost. The play was published in 1965, making Ama the first published African playwright. But whenever this fact was mentioned, Ama dismissed the idea: “ I don’t want to be the ‘first’ anything!” she would say scornfully.

She was appointed Secretary for Education in the second Jerry Rawlings Administration, the “PNDC”, in 1982. But being Ama, she criticised the emptiness of the "ideology" of some of the PNDC’s policies, to the face of Rawlings. So she only lasted a year in the Ministerial post.

She used to chuckle mischievously when she recalled her Ministerial tenure. “I was too much for everybody!” she said. Education was so important to her that she wasn't going to play tootsie with it to please anyone, including the widely-feared Jerry Rawlings.

Ama's novel, Changes, won the Commonwealth Writers’ Prize in 1992. In 2000, she established the Mbaasem Foundation, to give a practical expression to her desire to “promote and support the work of African women writers”.

Among other academic achievements, Ama held a fellowship in creative writing at Stanford University in California. She also taught English at Legon, where she later served as a research fellow at the Institute of African Studies. She further became a lecturer in English at the University of Cape Coast, where she eventually rose to the top and became a Professor.

Ama’s works portray the role of African women in contemporary society. She condemned, in her opus, the way that nationalism has been prostituted by some African leaders, into a means of keeping their people oppressed.

She is also critical of those literate Africans who profess to love their country but are seduced by, and sell their souls to be awarded the rewards that the "developed world" dangles before their eyes.

Following her departure from the Rawlings Government in 1983, Ama moved to live in Zimbabwe, where she continued her work in education, serving as a curriculum developer for the Zimbabwe Ministry of Education. While there, she published a collection of poems: Someone Talking to Sometime, as well as writing a children's book entitled The Eagle and the Chickens and Other Stories.

May she, I say again, rest in perfect peace.

Opinions of Saturday, 15 July 2023

Columnist: Cameron Duodu