A couple of weeks ago, Ghana had 208 new lawyers. 90% or more of that number must have started their pupilage in Accra and will remain in Accra after that.

A good number will not do litigation because their plans will see them employed in state and private institutions as some get to specialise or they will say “courtroom practice is just too demanding and difficult.”

The few that will “practice” will do so mostly in the three business capitals of Accra, Kumasi, and Takoradi and a couple other regional capitals serving a small number of people and entities in these urban areas which hold less than 65% of Ghana’s population but where over 96% of all licensed lawyers reside.

The 208 add to 2,599 lawyers licensed to practice, and of which number 2112, are based in Accra, 253 are in Kumasi, 58 are in Sekondi/Takoradi, 45 are in Cape Coast, 36 are in Koforidua and 92 are in Sunyani. The reality is a ratio of 1 lawyer to almost 80,000 people. But the graver reality is and as already noted, a good number of this number work in legal departments of one institution or the other and so they never get to interact with the people.

Now here is the point – the majority of the 26 million citizens simply don’t have access to a lawyer. But even if they did when they have the need for critical legal services including when they come face to face with the criminal justice system, they simply can’t afford the cost of the process and can’t hire a lawyer.

Yet the Constitution commands that the poor and indigent are entitled to legal services when they need it. The state insists in articles 14 and 19 of the Constitution that this is the only way to guarantee citizens a fair process and to protect their human rights when arrested, restricted or detained by police and that this is how to assure them of their dignity as human beings by giving them fair trial and justice.

The state then article 294 of the Constitution established a Legal Aid Scheme in 1997 to ensure that rule of law and access to justice extends to the poor and vulnerable who would otherwise be excluded from the formal justice delivery system. Take a trip to the head office of this vital institution of democracy in and tell me we are serious about what we profess in this regard.

Several dozens of poor vulnerable citizens needing critical legal services are seen in front of the office daily but enter these offices and see for yourself the conditions under which the few lawyers and paralegals there work. Well, that’s a topic for another discussion.

My Take today is to simply ask the question why we cannot have a policy or law to train and allow paralegals to fill the void created by the lack of lawyers. Truth is that there most likely will never be lawyers in our deprived communities to give meaning to what we profess in the Constitution.

District courts are mostly run by non-lawyer magistrates, police prosecutors doing cases in the name of the Attorney-General obviously are not lawyers. So I dare say it doesn’t make sense to continue to insist that the system should not accommodate paralegals.

It is, however, comforting that Chief Justice Sophia Akuffo believes paralegals can play a pivotal role in the justice delivery system and I sincerely hope Ghana will emulate the best examples quickly enough to give true meaning to its pledge of a democracy of freedom and justice.

I dedicate My Take today to the Ghana Legal Aid Scheme and the UNDP as they hosting a policy dialogue on the 31st of October 2017 on the theme: Delivering SDG Goal 16 in Ghana: Paralegals for increased access to Legal Aid Services.

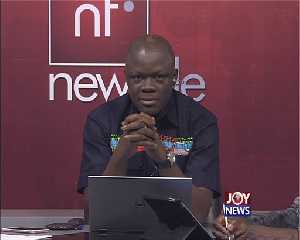

Samson Lardy ANYENINI

October 28, 2017

Opinions of Saturday, 28 October 2017

Columnist: Samson Lardy Anyenini