Television is a window to the world and that people will see that world or not, will learn from it or not.

But it is there so it makes no sense to say “we will pull down the shades when it comes to trials in Ghana”.

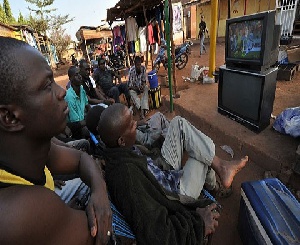

Reading a trial in the newspapers and seeing it on television sets are two quite different experiences the 2012 Supreme Court election petition has thought many Ghanaians.

A man who is found not guilty ordinarily may resume his life. A man who is found not guilty but has been on television during trial may find it impossible to resume his life. Audiences may even forget if he was found guilty or not.

History of the 2012 Supreme Court live broadcast indicates that the public is interested in viewing courtroom proceedings if the subject of the trial is wrapped in celebrity, an unorthodox and independent minded politicians and sensational details, “the pink sheet”.

No one even have to tell you the reader the name of the plaintiffs in the most publicized case in Ghana history, the plaintiffs in the 2012 presidential election petition-Nana Akuffo Addo and Dr. Mahamudu Bawumia.

The cast of characters in 2013 televised trial became as famous as any TV or movie star including Justice William Atuguba, other panel judges, lead counsel for the plaintiffs’ Lawyer Philip Addison, lead counsel for the plaintiffs’ Lawyer Tsatsu Tsikata and Dr. Mahamudu Bawumia the witness.

One poll showed that over 60% of Ghanaian population could identify lawyer Philip Addison or Dr. Mahamadu Bawumia who earned the nickname “PINK SHEET”, but only 25 percent knew who the president was at the time [Mr. John Dramani Mahama] as some persons mistook Nana Akuffo Addo for the president at that time.

According to Ghana Television Report over the period January-September 2013, television viewing increased by about 8% partly due to the euphoria that surrounded the elections 2012 and its aftermath.

The Supreme Court hearing on the election petition in some areas accounted for a sharp rise of about 32% in viewership for some networks that covered the court proceedings, the report revealed.

HEALTHY ARGUMENT BEGINS.

So a healthy argument for the lifting of the ban on television cameras in Ghanaian courts and precincts began immediately the Supreme Court delivered its ruling on the 2012 election petition in Ghana.

Those that argued for the lifting of the ban challenged that opening the courtroom to the television eye might increase public understanding of the judicial system, but only if coverage extends beyond TVs need to dramatize the sensational moment.

The traditional argument against allowing television cameras in the courts was that they were, by their nature, intrusive, that is they were distracting and noisy.

These arguments weakened as the media technologies improved, and, especially as television technologies became less physically cumbersome.

However other arguments began to surface for example, it was claimed that the presence of cameras could create psychological problems for judges, lawyers witnesses and juries as well.

The argument for allowing cameras in the courts continued along the same lines used from the beginning: the press had absolute right to cover trials as guaranteed by the Chief Justice administrative order in the case of the 2012 election petition in Ghana and to do so by using whatever tools of the trade were available to make it.

BAN ON CAMERAS.

To get to the heart of the matter, it would be appropriate to provide a short history of the controversy, which began with the intention and development of photography in the mid-nineteenth century.

At that point, it became possible to provide the citizens with a view of the American, British and civilized society court system never witnessed except by the tiny minority that had actually been in courts.

In 1925, parliament in United Kingdom banned photography in court cases law meaning the ban includes filming in courts.

A primary reason for the ban was that photography and filming and publication of images gained could put added strain on witnesses, defendants and jurors.

Section 41 of the criminal justice Act 1925 in United Kingdom made it illegal to: *take or try to take any photograph or film or,

*make or try to make-with a view to publication-any portrait or sketch of,

*any person in any court, its building, or within its precincts

*any person entering or leaving a court building or its precincts or,

*publish such a photo, film, portrait or sketch.

But from the outset, there were concerns expressed that the presence of still cameras in the courts would be an intrusion on the proceedings and damage the dignity if not the sanctity of the courts.

Many jurists believed that the purpose of a trial was not to inform or educate the public but to conduct a rigorous search for truth and that court proceedings were designed to do just that.

In fact the first live television broadcast of a trial took place in Waco, Texas on December 6, 1955. The judge, of course, approved but so did the jury and even the defendant, who was being tried for murder.

The American Bar Association tended toward the view that the defendant’s rights outweighed the rights of the press and, in 1965 received support from a decision by the U.S. Supreme court in the case of Estes v Texas.

Billy Sol Estes was a prominent political figure who had been convicted in a Texas courtroom in 1962 for fraudulent financial dealings.

The trial judge as was the predisposition in Texas courts, allowed photographers and TV cameras into the courtroom during pretrial hearings.

The U.S. Supreme court reversed Estes conviction on the grounds that the broadcasting of “notorious criminal trials “was a denial of the defendant’s right to due process.

In addition to citing the fact that the cameras had been a distraction, the court, in a five-to-four ruling, made a broad condemnation of television claiming that the use of in-court cameras was itself unfriendly to the judicial process.

The court claimed cameras could corrupt a juror’s impartiality, impair the testimony of witnesses, affect a judge’s decision and subject the defendant to mental harassment.

But the press continuing insistence that it was being denied its constitutional rights kept the door ajar.

In 1977, the state of Florida broke the door down as in that year; a pilot project began under the auspices of the state supreme court, allowing trials to be televised.

Among the trials included in the pilot project was that of Ronny Zamora, a fifteen-year old charged with murdering an eighty-two year old woman.

The trial received national attention not only because it was televised, but also because of Zamora’s defence.

He had been made insane he claimed, by watching violent television programmes.

Presiding judge Paul Baker, who had originally been opposed to the pilot project, concluded by the end of the trial that the courts and the electronic press can work harmoniously.

The tide began to turn. In fact in the following year, the U.S. Supreme Court in effect reversed itself on Estes.

Two former Miami Beach policemen who had been found guilty of burglary, Noel Chandler and Robert Granger, appealed their convict, arguing that the presence of TV cameras at their trial influenced the behaviour of attorneys, witnesses and jurors.

They relied heavily on the court’s reasoning in Estes, but it didn’t work.

A considerable number of legal organizations, states chief justices, and state attorneys general field briefs with the court, maintaining that cameras in no way harmed the judicial process.

The Supreme Court agreed as did many state legislatures throughout the country.

By the time Chandler v Florida was decided, twenty nine states had adopted rules allowing cameras on either a permanent or experimental basis.

And by April 1987, forty three states had some form of rules permitting camera coverage during trials although only twenty-seven states allowed coverage of criminal trials.

So in America and Canada, trials are always public that journalists, interested parties, and ordinary citizens have access to the proceedings.

In these countries there is nothing secret about the matter except in those instances where a judge confers privately with opposing counsels on some technical legal issues.

In concluding, the Chief Justice Her Ladyship Mrs. Sophia Akuffo, could write her legacy in Ghana by breaking the door down as she embarking on a year project allowing filming in our law courts.

Author is an NCTJ media law and court reporting student based in Toronto-Canada.

End.

By: Stephen A.Quaye, Toronto-Canada.

Opinions of Wednesday, 4 July 2018

Columnist: Stephen A.Quaye