At the root of Judaism, Christianity and Islam is the worship of the Black God of antiquity. The differences that currently exist in these three religions are due to a gradual perversion of an ancient religious order that permeated the world beyond the ancient near east.

In the seminal book The Proto-Semitic Religion, Professor Werner Daum tries to reconstruct the religion of the Proto-Semites – the forbears of the Semites of today. He claims that circa 9,000 years ago an African people crossed over into Southern Arabia and formed the basis of the Proto-Semitic peoples and religions. He further makes the point that these Proto-Semites worshiped a God they called A-Lah.

This was 9,000 years ago – long before ancient Kemet, the Bible, Qur’an or any of the prophets known to us. It is clear that southern Arabia (Yemen), Ethiopia and Eritrea shared a common religion. Daum’s documents reveal that the Kingdoms of Saba (Biblical Sheba), D’mt and Aksum called their God LMQH, which past and current scholars conventionally pronounce as Al-Maqah or God of Maqah. All of this predates the Hebrew deity El. The God El is a linguistic mutation of the God A-lah or AL.

This is a poignant revelation in carefully and correctly situating Allah in Africa – a God who was both worshipped by Africans on the continent and equally so by those who had migrated out.

Julian Baldick, in his book The Black God: The Afroasiatic Roots of the Jewish, Christian and Muslim Religions, makes the convincing argument that just as there exists a common Afroasiatic language group there also exists a common Afroasiatic fountain of religion. He asserts that “the God of the Bible comes out of the original Semitic Black Rain-Deity.”

With this background, Jacques Cauvin’s book The Birth of the Gods and the Origin of Agriculture becomes not only interesting but increasingly significant. Cauvin traces the origins of the neolithic agricultural revolution to the emergence of a new religion in the Levant circa 12,000 years ago.

He argues that around that time a new religious order marked by a change in symbolism sparked the agricultural revolution that put an end to hunting and gathering and ushered in a sedentary way of life typical of agrarian societies.

Cauvin notices that around the same time the structures dedicated to God began to take on the shape of a square rather than a circle. These square structures became the forebears of the Ziggurats and pyramids of the ancient near east and other places.

One of the oldest Ziggurats known, of Mesopotamian origin, assumes the form of a step pyramid (with seven steps). Cauvin claims that the transition from round religious buildings to square buildings represented the transformation of God as a spiritual being to God as Man. This God was represented by a Black Bull with his goddess by his side.

This God was a Black Man. The worship of this Black Man–God was codified in a set of religious structures around which grew rituals that were to survive thousands of years, allowing them to be adhered to even today.

The Black Man-God formed the basis of what we today call Judaism, Christianity and Islam.

The Hebrews copied many of these ancient beliefs and incorporated them into their religious structures. The Tabernacle of Moses spoken of in the Old Testament (OT) in the Bible was based on this ancient belief in the incarnation of the spirit of God in human form.

In Hebrew, the tabernacle is called Mishkan, which translates as the dwelling or residence in the same way that the Ziggurat was also seen to be the dwelling place of God.

The Ziggurat was taken care of by the priest, the only one admitted into the shrine of the God at the top of the Ziggurat. It was supposed to be the residence or dwelling place of the God worshiped by the Israelites. The tabernacle was built after the square form that Prof. Cauvin talked about in his book. It was deemed to be the house of God.

This incarnation of God in Man is covertly spoken of in the book of Genesis, however its reality and its distinction have escaped the average Jew and Christian. Most people who read the Genesis creation account think it to be the formation of the first man separate and distinct from God himself.

However, scholars agree that the Genesis creation account is of priestly origin and was thus written in esoteric language–the meaning of which was only known to the priests and the initiated.

Thus the verse “let us make man in our image and after our likeness” is pregnant with esoteric meaning. First, most English translations of this verse are inaccurate. The precise reading should be: “Let us make man as our image and after our likeness.”

The Hebrew do not say ‘in’ our image (selem) but ‘as’ our image (selem). Still, the translation of selem as image doesn’t do the word justice. In a very important article published in the Journal of Northwest Semitic Languages, Prof. I. H. Eybers traces the S-L root of Hebrew words. Prof. Eybers states that the word selem is derived from the root s-l-m which means (1) cult statue and (2) black. Hence, Adam is the Black statue that would house the spirit or breath of God. Adam is thus the incarnation of God.

H. Wildberger writes in Das Abbild Gotten: “It cannot be stressed enough that Israel… by a daring adaptation of the image theology of the surrounding world, proclaims that a human being is the form in which God himself is present.” This is also confirmed by Andreas Schule in his book The Concepts of Divine Images in Genesis 1-3: “The Cultic image is… the medium of manifest divine presence and action in the world and as such part of the divine. It is to put it pointedly, god on earth.

The image was…. that side of the God’s person through which he entered the sphere of created life… the bodily appearance of a God, the very medium… through which he can be addressed by prayer, worship and sacrifice.”

It seems that this original divine incarnation of God in man (Adam) provided the basis for a later cult-statue worship that would permeate the ancient near east. The tabernacle of Moses was simply a copy of this religious concept of God’s divine spirit dwelling on earth as a man. While the Israelites partook of this ancient cult-statue reverence of the Black God, a similar religious activity occurred to the south of Israel in what is called Arabia.

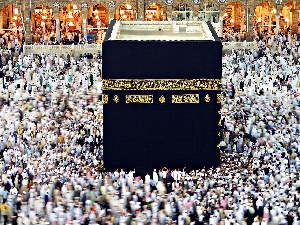

In Arabia an ancient cult was built around a cube-like structure in Mecca (bakkah) that was dedicated to the ancient God called Allah. This cube was and is called the Ka’bah or the Al bayt Allah — the House of God. It is built like the tabernacle of Moses to represent the dwelling of God and is similarly covered with veils.

Contrary to the perception of the pedestrian Muslim, the Kabah and its associated rituals predate Prophet Muhammad by at least 1,000 years. In fact, before the prophet-hood of Muhammad he used to go on pilgrimages to the Kabah just as pre-Quranic Arabs did.

The Kabah was the religious structure dedicated to a God called Allah, similar to the God A-lah of the Proto-Semitic peoples who migrated to Arabia 9,000 years ago from Africa. This ancient God’s name was immortalized through rituals around the Kabah. It is this ancient God of the Black Proto-Semites that through time mutates into the El, Eloh and Elohim of the Old Testament. The Kabah houses a Black meteorite stone deemed to be part of the Deity’s astral body.

In the article “Origin And Significance of the Magen Dawid: A Comparative Study in the Ancient Religions of Jerusalem and Mecca” in the Quarterly Journal in African and Oriental Studies (Archi orientalni), Hildegard Lewy writes that “the black stone was thought to be part of the body of a great God.”

Cheikh Anta Diop describes the similarities between the Arab religion and the religion of ancient Kemet. He particularly notes that some Islamic rituals were named after certain ontological Kemetic words such as Ra, Ka and Ba. He states that: (1) KABAR means the raising of the arms in prayer in Islam, (2) RAKA is the action of placing the forehead on the ground during prayer in Islam and (3) KABA refers to the holy house of God in Mecca.

These similarities between Kemet and Islam become even more apparent when one considers the ontology of the Kemetic words KA, BA and KHAT: (1) KHAT means the immortal body of God, (2) KA means the mortal or physical body of God and (3) BA means the Breath or Spirit of God.

The fact that the Islamic Kabah refers to the physical body (KA) housing the spirit (Ba) of God is no mere coincidence. Does it mean that Islam is an ancient Egyptian religion? No, the data does not allow us to make such a claim. However, it confirms that Ma’at and Islam are cognate religions–children of a common parent religious order at the very least.

Diop also documents that the Kemetic priests fasted for thirty days each year just like in Islamic Ramadan. We are further told that at a certain Temple in Kemet a replica of the God Osiris was placed inside the Temple and the priests of Kemet would circumambulate the Temple in the same way that Muslims circumambulate the Kabah. More to this point, the records show that the Kemetic Priests performed this ritual exactly seven times – the number of times that Muslims do at the Kabah.

Serge Sauneron documents more similarities between Ma’at of ancient Kemet and Islam in his book The Priests of Ancient Egypt. He documents that the Priests of Ancient Egypt performed ablutions four times a day before prayer just like in Islam; although Muslims now pray five times a day, only four prayer times are mentioned in the Qur’an.

Like the Bible, the Qur’an also squares face to face with God’s incarnation as Adam. The Qur’an is however more direct and overt in its description of Adam’s creation by Allah. In Chapter 15:28 it states: “And when your Lord said to the angels: I am going to create a mortal of sounding clay, of Black mud fashioned into shape.”

Thus, in similar fashion as in the book of Genesis, the Adam spoken of here is of Black complexion. Muslims would argue that the Quranic Adam is simply a man and not God incarnate, but such a view becomes problematic in light of the order, which Allah gives the angels to bow down to Adam after God made him complete with His Spirit in Chapter 13:15: “Whoever is in the heavens and the earth makes obeisance to Allah ONLY, willingly or unwillingly…” Chapter 16:48-50 continues: “And don’t they observe anything created by Allah how it casts its shadow right and left, doing its obeisance to Allah ALONE?

Thus do all things express their humility to Allah. All the living creatures in the heavens and the earth and all the angels make obeisance in adoration of Allah ALONE…”

The above verses make it clear that ‘prostration’ or obeisance is due to Allah ALONE, so how come angels are asked to bow down to Adam if he wasn’t a God, or if he wasn’t God Himself?

To the east of Arabia another remarkable civilization developed in the Indus Valley of what is now India. It followed a religious order that would later have the Supreme God Vishnu incarnate in Krishna–a Sanskrit word that literally means Black or Dark. Is it a coincidence that yet another people harbored the belief that God incarnated in a Black man?

Wesley Muhammad, a professor of religion, documents that the Buddhists have a ritual called Pradakshina where they circumambulate a Stupa, which is a mount-like structure containing religious relics. The Buddhists inherited this practice from their Hindu forebears who engaged in this ritual in ancient times. Here again we find similarities between Hinduism, Buddhism, Islam and Ma’at – where adherents circumambulate a structure deemed to be the body of the Black God.

African Traditional Religions (ATRs) are connected to this ritual and belief of the Supreme Being’s incarnation in man. The shrines that are so common in numerous ATRs are an outgrowth of this concept of God dwelling among men and the need for the physicality of God on Earth in order for us, as humans, to interact with Him.

When African Traditional worshipers pray they direct their prayers to the God of the shrine, usually a family God. Certain items like stones, wood, figurines or jewelry would be used to represent the physical presence of the God.

This belief among our traditionalists emanates from the ancient religious order that one could only request help from a physical reality and not a vacuum or space. One had to direct one’s prayer to the physical representation of God.

Here, too, we find a similar practice in Islam called the qibla, or the direction of prayer. When Muslims pray they face in a direction toward the Kabah, the physical representation of God. Before prophet Muhammad conquered Mecca in 630 A.D, the Muslims faced Jerusalem toward the Temple of Solomon which represented the house of God. The Israelites prayed facing the tabernacle of Moses or the temple. Jewish people also pray facing the ‘wailing wall’ as one has to face a physical representation of the presence of God.

What we find in the ancient world is a universal adoration and belief system in a God incarnated in a Black man. White angels, Jesus and God are only recent inventions in line with the machinations of White supremacy.

Opinions of Thursday, 28 July 2016

Columnist: Atiga Atingdui