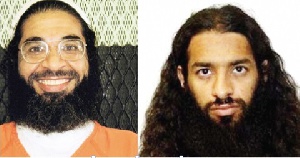

Following the decision of the Obama-led administration in the United States of America to shut down the Guantanamo Bay detention facility, it went into agreements with various governments around the globe to resettle some of the detainees. In 2016, a back-door agreement with the John Mahama administration resulted in two of the detainees from Yemen – Mahmud Umar Muhammad Bin Atef and Khalid Muhammad Salih Al-Dhuby (popularly referred to as the Gitmo2 by Ghanaians) – being resettled in Ghana. The two had been detained at the Guantanamo Bay for 14 years after they were linked to the Al-Qaeda terrorist group.

The decision to bring in these two detainees received a strong backlash from the Ghanaian public, including the religious community, who thought that the presence of the two in the country would posed a threat to Ghana’s national security. The government’s plea for Ghana to accept them on compassionate grounds did not make much impact.

Following that, a case was brought before the Supreme Court to determine if the Mahama government’s back-door deal did not violate article 75(2), among other provisions, of the 1992 Constitution. The Court ruled in favour of the applicants and asked the government to rectify the agreement within three months.

Yet, the issue would not go away because by early 2018, the two-year period allotted the Gitm2 had become due. The Minister for Foreign Affairs and Regional Integration, Madam Ayorkor Botchway, was subsequently summoned before Parliament to inform the august house about the fate of the Gitmo2. Ghanaians were shocked to learn that the two are staying put because they were granted refugee status on 21 July 2016 by the Mahama administration, following a request by the National Security to the then-Chairman of the Ghana Refugee Board.

The Minster explained further that “the implication is that, in accordance with the United Nations Convention on the Status of Refugees of 1951, and the 1967 protocol on the Status of refugees as well as the provisions of the Refugee Law (1992) PNDC Law 305 (d) of Ghana, the two have attained the status of refugees in our country.” She is reported to have noted further that “the essential component of the refugee status in Ghana is protection against return to a country where a person has reason to fear persecution. Accordingly, government is constrained to explore any further options at this time, and will await an in-depth examination of the matter by the appropriate agencies.” A Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs, Mr Wiredu, based on an interview in one of the FM radio stations is also reported to have said that “Once the two are here and they are obeying our laws and have not gone against the laws, it is difficult [to send them away] without their consent.”

Reaction

These developments and revelations raise a number of critical questions, which cannot be washed away simply by stating that the basis for granting them that status was because their country of origin was/is in turmoil; or they can only be taken out of the country if they misbehaved themselves.

Instead of the government being concerned about violating international law if we should expel the two, I think that we should rather explore whether the steps taken to grant the Gitmo2 refugee status violated international obligations and our local laws. If found true, it would render invalid the whole transaction and therefore grant the courts the power to determine that the process was legally flawed and therefore empowers the country to expel the foreigners.

5-plus grounds to claim refugee status

Ghana’s Refugee Act, 1992 (PNDCL 305D), recognises the 5 grounds for claiming refugee status recognised in the 1951 UN Refugee Convention in addition to an omnibus provision stipulated in the OAU Convention on the Status of Refugees. Combined, the Refugee Act provides that a person is entitled to claim a refugee status in Ghana if he has a well-founded fear that

(a) his life or freedom would be threatened on account of his race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion; or (b) his life, physical integrity or liberty would be threatened on account of external aggression, occupation, foreign domination or events seriously disrupting public order in that country or any part of it.

Yet, the Gitmo2 did not come to Ghana to seek refugee status based on any of the above grounds. Neither did they seek the refugee status as a result of changed circumstances in their country while in Ghana. The facts available to general public so far are that it was the National Security apparatus that initiated the process for them. Yet, that process is legally wrong. Refugee status is initiated by the individual applicant but not by governmental fiat, neither is it a diplomatic privilege which a government can exercise on behalf of another.

In the Nigeria case High Court case of Egbuna v Taylor, Anyaele v Taylor, where the applicants instituted the action to determine whether they could seek judicial review, in a domestic court, of an executive decision granting asylum to Charles Taylor, the former President of Liberia and a person who had been indicted by an international tribunal at the time of granting the refugee status. The applicants argued that Taylor had been wrongly granted asylum in Nigeria. In a preliminary objection, the Attorney-General of Nigeria argued that the act of granting asylum was a diplomatic issue and not one for the applicants. The court, however, ruled that it had jurisdiction to hear the matter, thereby dismissing the Nigerian government’s objection. Therefore, the decision by the National Security to grant the refugee status is equally wrong.

Hands tied?

Having established this fundamental faux pas to fault the granting of refugee status to the Gitmo2, the statement that, the fact that they are granted refugee status ties the government's hands is not founded. They can still be made to leave Ghana based on a number of factors. These are clearly spelt out in the Refugee Act and the Immigration Act, including the international conventions which are also part of Ghana’s law.

First, if the Refugee Board considers that the person “should not have been so recognised” in the first place (Section 15(1)(a) of the Refugees Act). This is a strong basis on which the Gitmo2 can be deported from the country, based on the above discussion.

Second, the refugee status can be revoked if the circumstances based on which the applicant sought refugee status has ceased to exist (section 15(1)(b) and 17(d) of the Refugee Act. Thus, unless they can tie their claim to the ongoing conflict, Ghana can deport the Gitmo2.

Another basis for supporting the right of Ghana to deport the Gitmo2 is found under section 35(1)(e) of the Immigration Act, which stipulates that a “foreign national is liable to deportation if his presence in Ghana is in the opinion of the Minister not conducive to the public good.” This is based on the general sense of revulsion felt by Ghanaians when the two were admitted into the country in the first place and when Ghanaians were told that they are now staying permanently.

One fundamental basis for the country’s unwillingness to let the two stay is based on the security implications for the country, whether justified or not. This provides a basis and justification under section 3 of the Refugee Act, which provides that “A refugee may be detained or expelled for reasons of national security or public order except that no refugee shall be expelled to a country where he has reason to fear persecution.”

Non-refoulement Seciton 3 of the Refugee Act introduces the non-refoulement principle. The Minister for Foreign Affairs is on record as having said that Ghana would be in violation of the non-refoulement principle if the two are returned to Yemen because of the on-going civil war in the country. However, that should not be the basis for determining the non-refoulement rule which places an obligation on country receiving asylum seekers not to return them to a country in which they would be in likely danger of persecution based on any of the prescribed grounds for claiming refugee status.

Instead of looking at the state of affairs in the country generally, the law says that we should rather look at whether, in spite of the state of affairs, the person has a well-founded fear of persecution on any of the grounds stated above. Thus, refugee status determination is based on a case-by-case basis. It is for this reason that in peaceful, democratic environments, some people are able to leave and successfully claim refugee status outside their country. And in the same way, people fleeing from civil war and violence in Syria, Iraq, etc have been denied refugee status. So it is important to know the basis for granting the Gitmo2 their refugee status. The government on its own, does not have the privilege to use executive fiat to grant refugee status.

Article 1F Rule

Article 1F of the UN Refugee Convention provides that if there is 'reasonable grounds to suspect' that a person has committed various international crimes, serious non-political crimes or acts that violate the principles and purposes of the UN, that person cannot claim refugee status or if he has, that status can be revoked. In this case, it needs not be proven that the person has been convicted of the wrong, which was the argument put up by the previous government to support its decision to bring them into the country. All that one needs to establish is that the government has reasonable grounds to suspect. If the US had such reasonable grounds and on those grounds, detained the two among others, for years at Guantanamo and we are able to access their records or find other means to establish same, international law allows us to ask them to leave the country.

Conclusion

The whole process operationalized to grant refugee status to the Gitmo2 violates the country’s obligations under the various global (UN) and regional (AU) refugee conventions. The country’s laws allow for rejecting such a refugee claim. The non-refoulement principle is not violated if the Gitmo2 are returned to their country. Moreover, it is possible to find a reasonable grounds to suspect that the two may have committed international crimes, serious non-political crimes or offences that violate UN and AU principles and purposes. On these bases, Ghana is justified to renounce the refugee status granted Mahmud Umar Muhammad Bin Atef and Khalid Muhammad Salih Al-Dhuby and cause their exit out of the country.

Opinions of Thursday, 25 January 2018

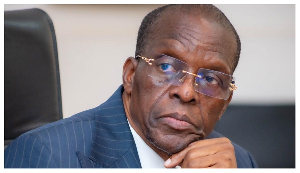

Columnist: Dr Kwadwo Appiagyei-Atua