Ghana welcomes its new President in a peaceful, democratic transfer of power

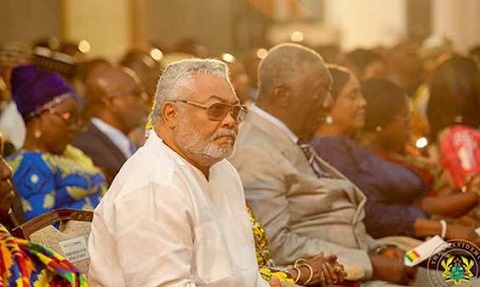

Such is the cynicism in sub-Saharan Africa that many Ghanaians expected leader Jerry Rawlings to tweak his country's constitution and permit himself another run for the presidency. What was such a powerful man expected to do, said the country's chattering classes, give up power? But after 11 years as dictator and a further eight as Ghana's elected President, the term-limited Rawlings did just that.

Faced with the task of picking Rawlings' successor, voters chose John Agyekum Kufuor. The longtime opposition leader, a free-market liberal often called the gentle giant of Ghanaian politics, handily defeated Rawlings' deputy, Vice President John Atta Mills, in a Dec. 27 runoff for the presidency. Neither of the major candidates attained the required majority in the first round on Dec. 7, and the endorsements of five minor candidates swung the runoff firmly in Kufuor's favor.

The inauguration of the new President on Jan. 7 — a rare peaceful transfer of power in West Africa — also seals what may be Rawlings' greatest legacy: the establishment of a vibrant multiparty democratic system. Yes, there were bumps in the road to the voting booth. Early in the electoral season, opposition leaders warned of serious irregularities with election arrangements, including the inflation of voter rolls with the names of dead or ineligible people. On Election Day, there were reports of voter intimidation from around the country, including attacks on opposition politicians by government loyalists and skirmishes between the two sides.

But the opposition still won. As each constituency's returns came in and as the tallies were scrawled on huge chalkboards in Accra's Independence Square, it was clear that voters had given the opposition New Patriotic Party (NPP) half of the seats in Parliament, relegating the governing National Democratic Congress (NDC) to the opposition benches for the first time. And three weeks later, the boards showed that Ghanaians had chosen Kufuor to be their fourth elected President in the 44 years since independence. The Vice President graciously conceded defeat, and Ghana exhaled in relief.

That's the good news for the NPP and its candidate. The bad news? Rawlings leaves behind a struggling economy with a slew of policy challenges and domestic dilemmas. In the early 1980s, he implemented a heavy-handed program of austerity and price controls that sent the economy reeling. A subsequent about-face and an embrace of more free-market principles endeared him to the West, but the economy has not fared much better. In 2000, Ghana's currency, the cedi, lost about half its value against the U.S. dollar. The markets for Ghana's two major export commodities — cocoa and gold — have been soft; cocoa prices dipped about 10% over the past year, while gold sells for about 30% less than it did five years ago. And at least a third of the population is unemployed.

Corruption and mismanagement of official funds are major problems. Bribery and graft remain endemic in a country where renewing one's driver's license can require slipping some cash to everyone from the bureaucrat handling the paperwork to the typist who fills in the forms. While Ghana has received billions of dollars in grants and loans from international governments and institutions in recent years, including $4 billion from the World Bank, much of the money has been squandered by politicians and civil servants. This writer saw various government ministries' fleets of sport-utility vehicles — many emblazoned with the name of the foreign agency supplying the funding — and bureaucrats shuttled around by chauffeurs while millions of Ghanaians live without electricity or running water.

While Kufuor campaigned on a platform of "positive change," nobody expects him to address the litany of issues quickly. But the political stability reflected in his election and inauguration does inspire some much-needed confidence, not only among the electorate but also with the international community and investors seeking opportunities in the Third World. Ghanaian founding father Kwame Nkrumah reportedly once said, "We would rather misgovern ourselves than be governed properly by others." With the Rawlings-Kufuor handover, Ghana may have taken one more step toward becoming the rare state in West Africa that governs itself democratically. One can only hope it will become that even rarer nation that does the job well.